1.1. Introduction#

1.1.1. The Graphics Processing Unit#

Born as a special-purpose processor for 3D graphics, the Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) started out as fixed-function hardware to accelerate parallel operations in real-time 3D rendering. Over successive generations, GPUs became more programmable. By 2003, some stages of the graphics pipeline became fully programmable, running custom code in parallel for each component of a 3D scene or an image.

In 2006, NVIDIA introduced the Compute Unified Device Architecture (CUDA) to enable any computational workload to use the throughput capability of GPUs independent of graphics APIs.

Since then, CUDA and GPU computing have been used to accelerate computational workloads of nearly every type, from scientific simulations such as fluid dynamics or energy transport to business applications like databases and analytics. Moreover, the capability and programmability of GPUs has been foundational to the advancement of new algorithms and technologies ranging from image classification to generative artificial intelligence such as diffusion or large language models.

1.1.2. The Benefits of Using GPUs#

A GPU provides much higher instruction throughput and memory bandwidth than a CPU within a similar price and power envelope. Many applications leverage these capabilities to run significantly faster on the GPU than on the CPU (see GPU Applications). Other computing devices, like FPGAs, are also very energy efficient, but offer much less programming flexibility than GPUs.

GPUs and CPUs are designed with different goals in mind. While a CPU is designed to excel at executing a serial sequence of operations (called a thread) as fast as possible and can execute a few tens of these threads in parallel, a GPU is designed to excel at executing thousands of threads in parallel, trading off lower single-thread performance to achieve much greater total throughput.

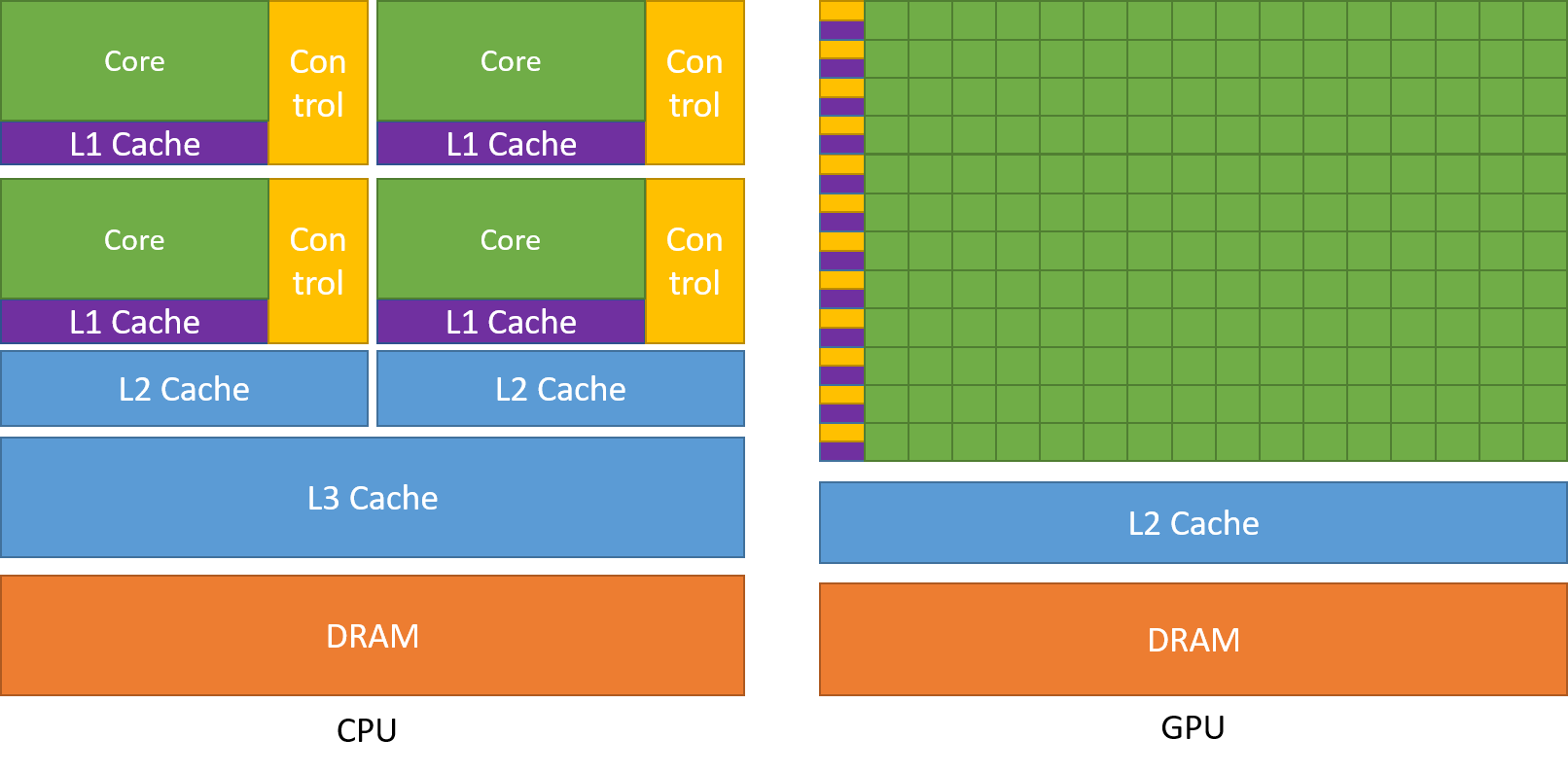

GPUs are specialized for highly parallel computations and devote more transistors to data processing units, while CPUs dedicate more transistors to data caching and flow control. Figure 1 shows an example distribution of chip resources for a CPU versus a GPU.

Figure 1 The GPU Devotes More Transistors to Data Processing#

1.1.3. Getting Started Quickly#

There are many ways to leverage the compute power provided by GPUs. This guide covers programming for the CUDA GPU platform in high-level languages such as C++. However, there are many ways to utilize GPUs in applications that do not require directly writing GPU code.

An ever-growing collection of algorithms and routines from a variety of domains is available through specialized libraries. When a library has already been implemented—especially those provided by NVIDIA—using it is often more productive and performant than reimplementing algorithms from scratch. Libraries like cuBLAS, cuFFT, cuDNN, and CUTLASS are just a few examples of libraries that help developers avoid reimplementing well-established algorithms. These libraries have the added benefit of being optimized for each GPU architecture, providing an ideal mix of productivity, performance, and portability.

There are also frameworks, particularly those used for artificial intelligence, that provide GPU-accelerated building blocks. Many of these frameworks achieve their acceleration by leveraging the GPU-accelerated libraries mentioned above.

Additionally, domain-specific languages (DSLs) such as NVIDIA’s Warp or OpenAI’s Triton compile to run directly on the CUDA platform. This provides an even higher-level method of programming GPUs than the high-level languages covered in this guide.

The NVIDIA Accelerated Computing Hub contains resources, examples, and tutorials to teach GPU and CUDA computing.