1.2. Programming Model#

This chapter introduces the CUDA programming model at a high level and separate from any language. The terminology and concepts introduced here apply to CUDA in any supported programming language. Later chapters will illustrate these concepts in C++.

1.2.1. Heterogeneous Systems#

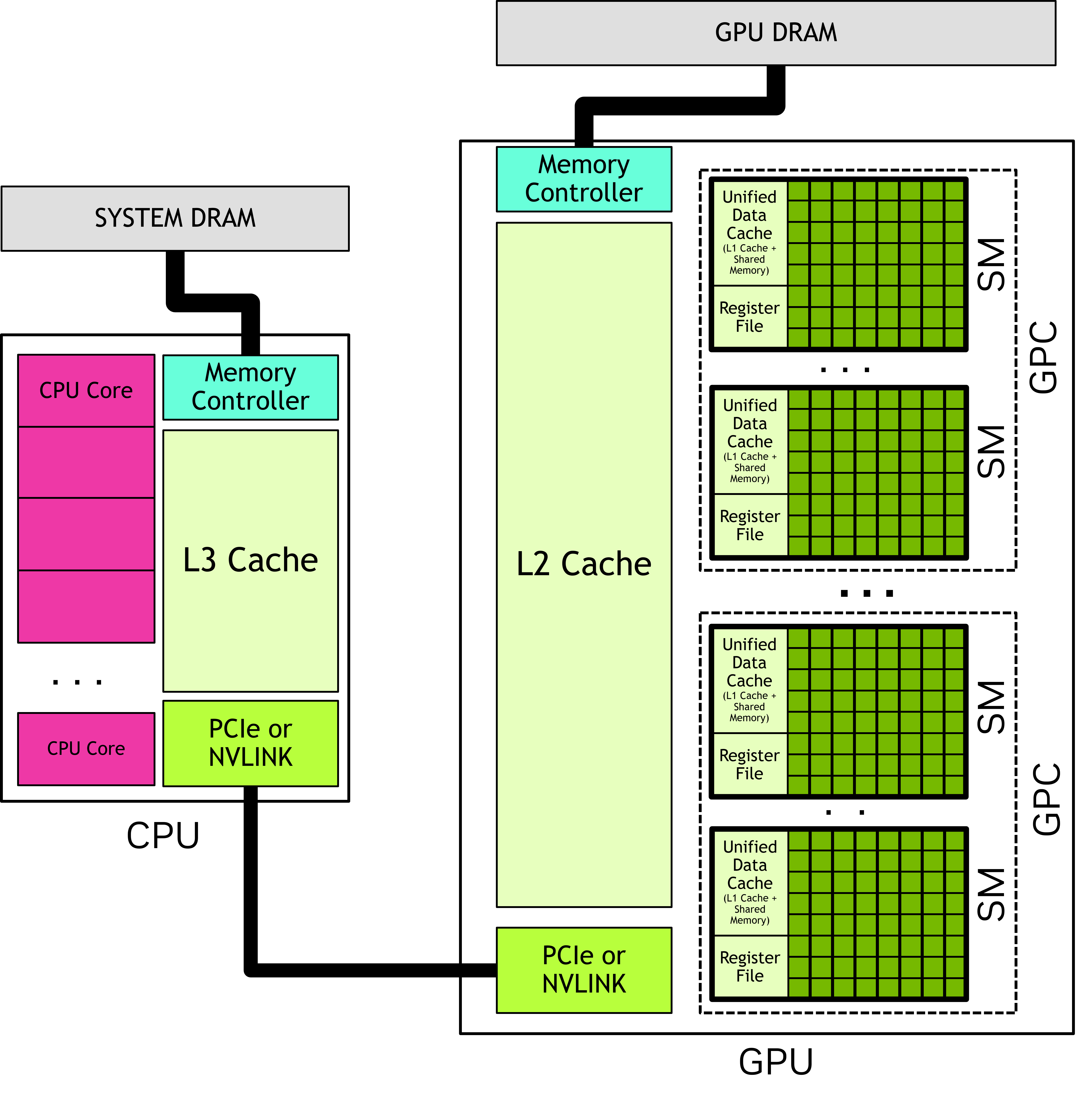

The CUDA programming model assumes a heterogeneous computing system, which means a system that includes both GPUs and CPUs. The CPU and the memory directly connected to it are called the host and host memory, respectively. A GPU and the memory directly connected to it are referred to as the device and device memory, respectively. In some system-on-chip (SoC) systems, these may be part of a single package. In larger systems, there may be multiple CPUs or GPUs.

CUDA applications execute some part of their code on the GPU, but applications always start execution on the CPU. The host code, which is the code that runs on the CPU, can use CUDA APIs to copy data between the host memory and device memory, start code executing on the GPU, and wait for data copies or GPU code to complete. The CPU and GPU can both be executing code simultaneously, and best performance is usually found by maximizing utilization of both CPUs and GPUs.

The code an application executes on the GPU is referred to as device code, and a function that is invoked for execution on the GPU is, for historical reasons, called a kernel. The act of starting a kernel running is called launching the kernel. A kernel launch can be thought of as starting many threads executing the kernel code in parallel on the GPU. GPU threads operate similarly to threads on CPUs, though there are some differences important to both correctness and performance that will be covered in later sections (see Section 3.2.2.1.1).

1.2.2. GPU Hardware Model#

Like any programming model, CUDA relies on a conceptual model of the underlying hardware. For the purposes of CUDA programming, the GPU can be considered to be a collection of Streaming Multiprocessors (SMs) which are organized into groups called Graphics Processing Clusters (GPCs). Each SM contains a local register file, a unified data cache, and a number of functional units that perform computations. The unified data cache provides the physical resources for shared memory and L1 cache. The allocation of the unified data cache to L1 and shared memory can be configured at runtime. The sizes of different types of memory and the number of functional units within an SM can vary across GPU architectures.

Note

The actual hardware layout of a GPU or the way it physically carries out the execution of the programming model may vary. These differences do not affect correctness of software written using the CUDA programming model.

Figure 2 A GPU has many streaming multiprocessors (SMs), each of which contains many functional units. Graphics processing clusters (GPCs) are collections of SMs. A GPU is a set of GPCs connected to the GPU memory. A CPU typically has several cores and a memory controller which connects to the system memory. A CPU and a GPU are connected by an interconnect such as PCIe or NVLINK.#

1.2.2.1. Thread Blocks and Grids#

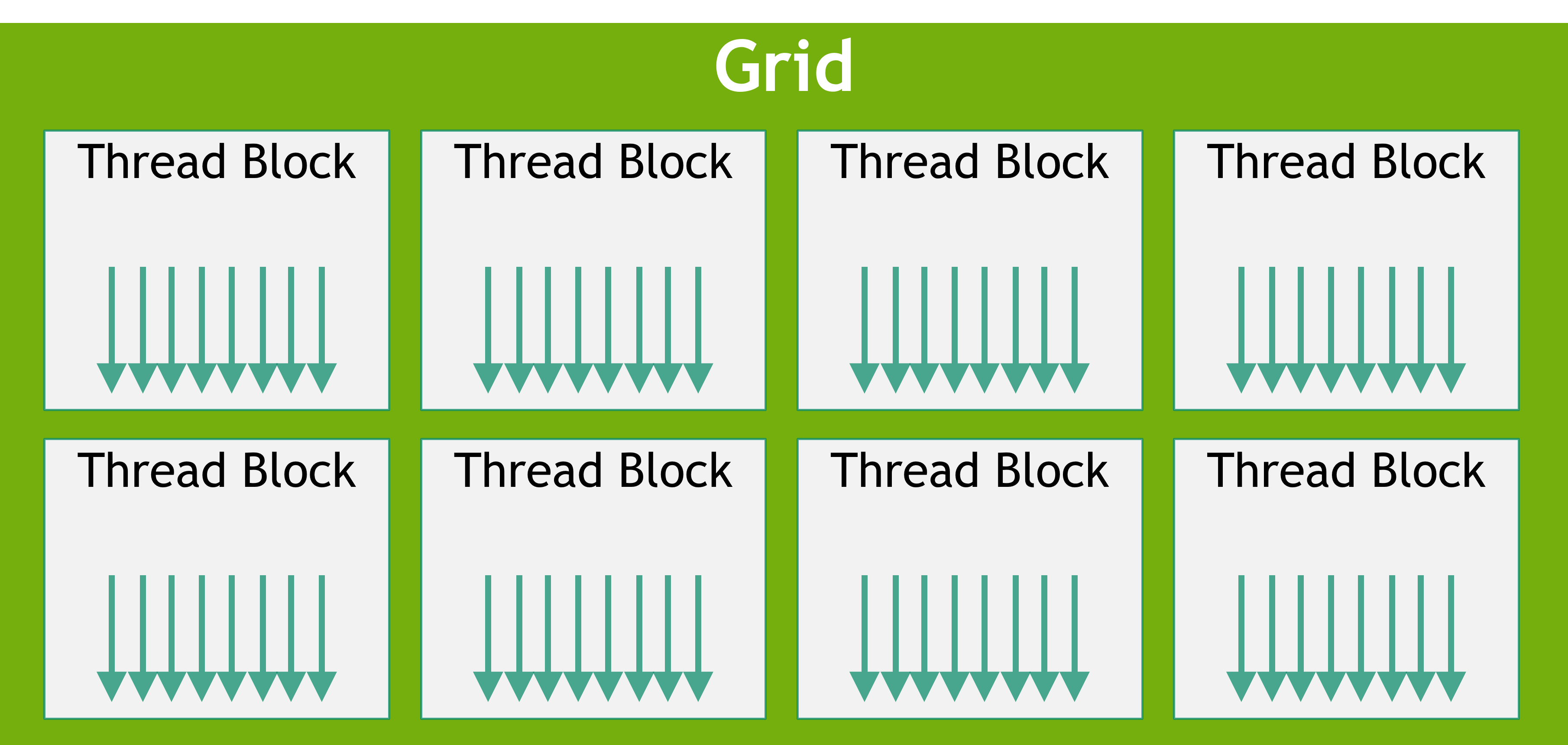

When an application launches a kernel, it does so with many threads, often millions of threads. These threads are organized into blocks. A block of threads is referred to, perhaps unsurprisingly, as a thread block. Thread blocks are organized into a grid. All the thread blocks in a grid have the same size and dimensions. Figure 3 shows an illustration of a grid of thread blocks.

Figure 3 Grid of Thread Blocks. Each arrow represents a thread (the number of arrows is not representative of actual number of threads).#

Thread blocks and grids may be 1, 2, or 3 dimensional. These dimensions can simplify mapping of individual threads to units of work or data items.

When a kernel is launched, it is launched using a specific execution configuration which specifies the grid and thread block dimensions. The execution configuration may also include optional parameters such as cluster size, stream, and SM configuration settings, which will be introduced in later sections.

Using built-in variables, each thread executing the kernel can determine its location within its containing block and the location of its block within the containing grid. A thread can also use these built-in variables to determine the dimensions of the thread blocks and the grid on which the kernel was launched. This gives each thread a unique identity among all the threads running the kernel. This identity is frequently used to determine what data or operations a thread is responsible for.

All threads of a thread block are executed in a single SM. This allows threads within a thread block to communicate and synchronize with each other efficiently. Threads within a thread block all have access to the on-chip shared memory, which can be used for exchanging information between threads of a thread block.

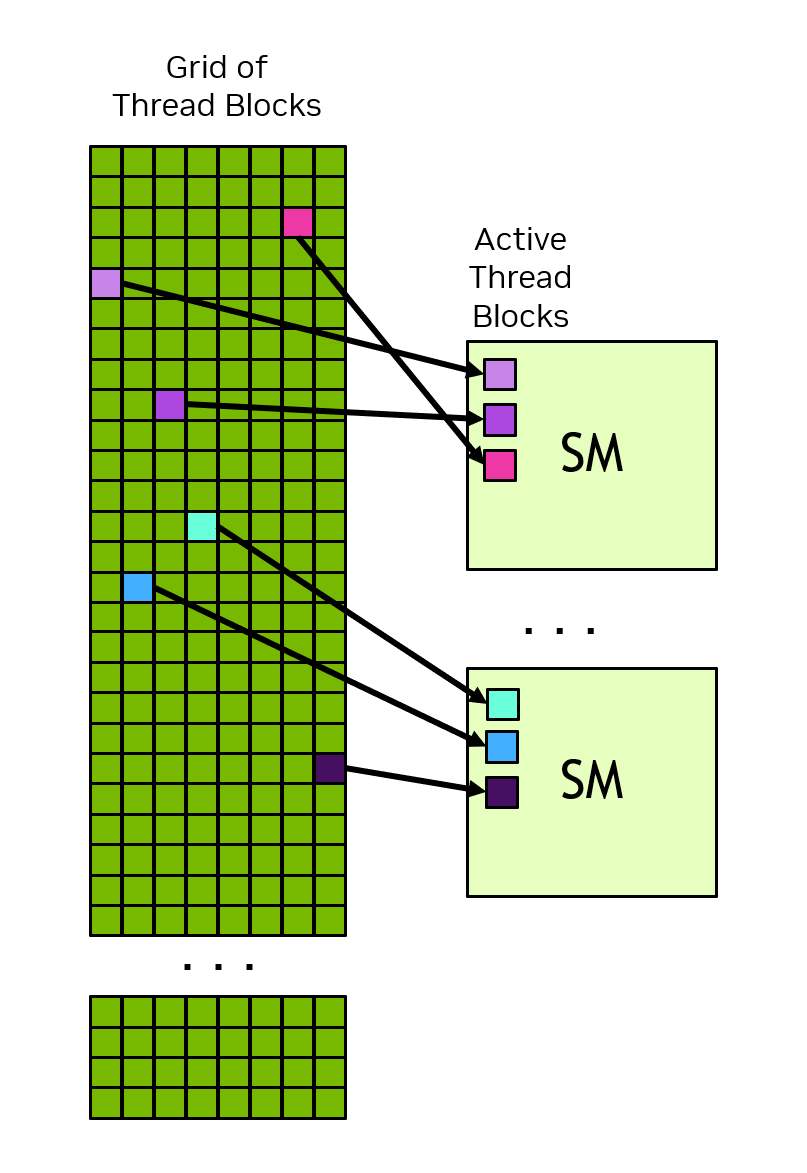

A grid may consist of millions of thread blocks, while the GPU executing the grid may have only tens or hundreds of SMs. All threads of a thread block are executed by a single SM and, in most cases [1], run to completion on that SM. There is no guarantee of scheduling between thread blocks, so a thread block cannot rely on results from other thread blocks, as they may not be able to be scheduled until that thread block has completed. Figure 4 shows an example of how thread blocks from a grid are assigned to an SM.

Figure 4 Each SM has one or more active thread blocks. In this example, each SM has three thread blocks scheduled simultaneously. There are no guarantees about the order in which thread blocks from a grid are assigned to SMs.#

The CUDA programming model enables arbitrarily large grids to run on GPUs of any size, whether it has only one SM or thousands of SMs. To achieve this, the CUDA programming model, with some exceptions, requires that there be no data dependencies between threads in different thread blocks. That is, a thread should not depend on results from or synchronize with a thread in a different thread block of the same grid. All the threads within a thread block run on the same SM at the same time. Different thread blocks within the grid are scheduled among the available SMs and may be executed in any order. In short, the CUDA programming model requires that it be possible to execute thread blocks in any order, in parallel or in series.

1.2.2.1.1. Thread Block Clusters#

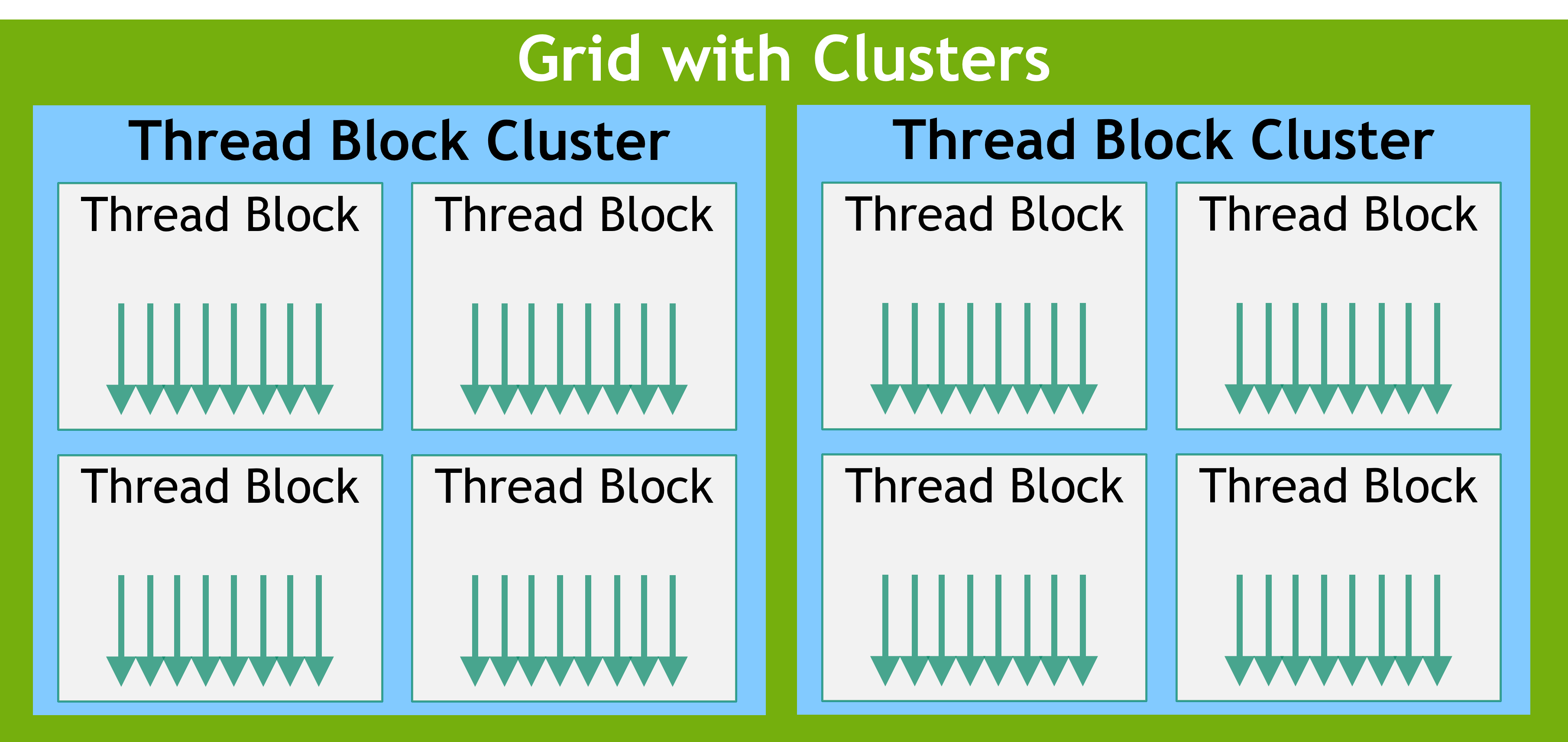

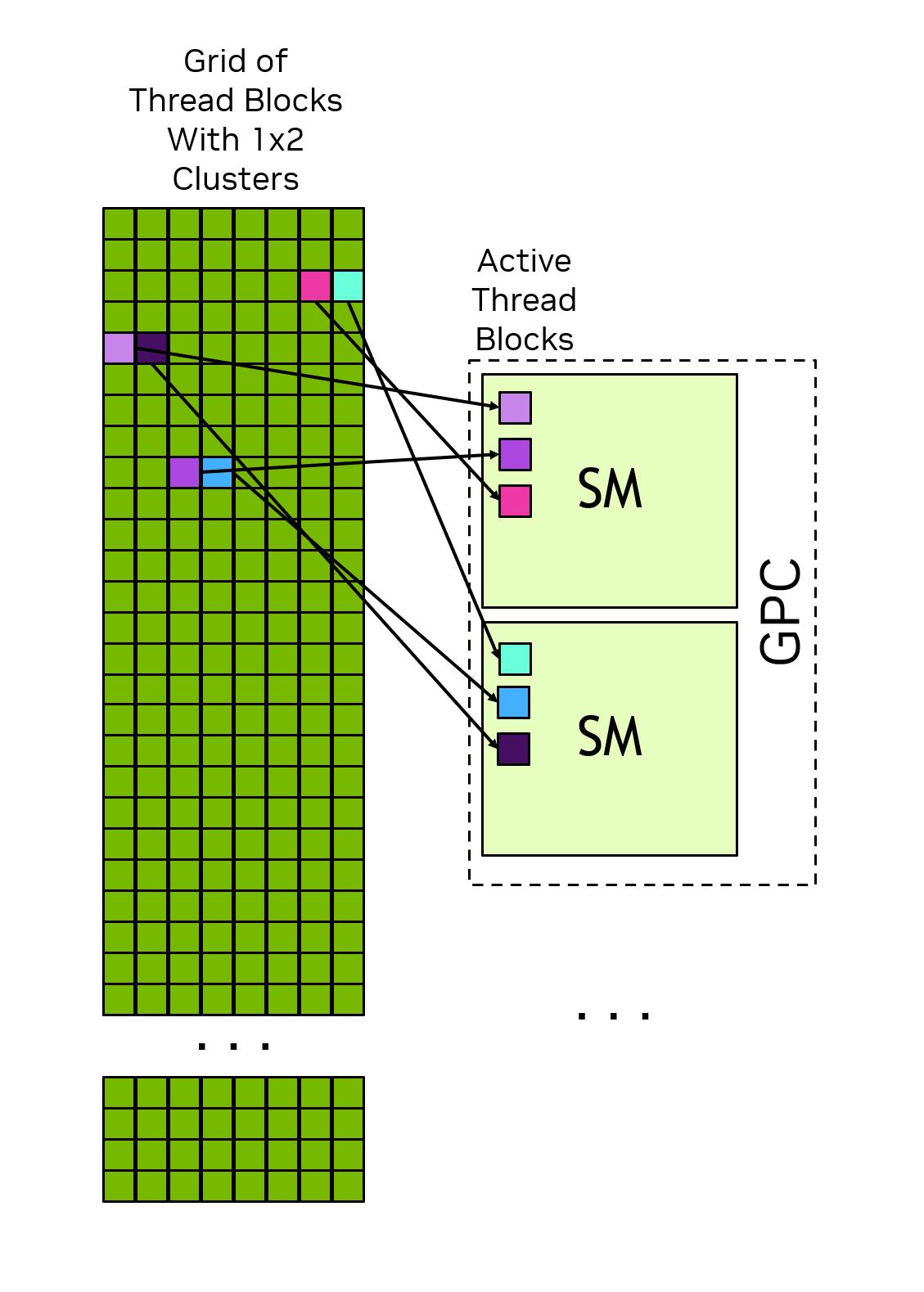

In addition to thread blocks, GPUs with compute capability 9.0 and higher have an optional level of grouping called clusters. Clusters are a group of thread blocks which, like thread blocks and grids, can be laid out in 1, 2, or 3 dimensions. Figure 5 illustrates a grid of thread blocks that is also organized into clusters. Specifying clusters does not change the grid dimensions or the indices of a thread block within a grid.

Figure 5 When clusters are specified, thread blocks are in the same location in the grid but also have a position within the containing cluster.#

Specifying clusters groups adjacent thread blocks into clusters and provides some additional opportunities for synchronization and communication at the cluster level. Specifically, all thread blocks in a cluster are executed in a single GPC. Figure 6 shows how thread blocks are scheduled to SMs in a GPC when clusters are specified. Because the thread blocks are scheduled simultaneously and within a single GPC, threads in different blocks but within the same cluster can communicate and synchronize with each other using software interfaces provided by Cooperative Groups. Threads in clusters can access the shared memory of all blocks in the cluster, which is referred to as distributed shared memory.The maximum size of a cluster is hardware dependent and varies between devices.

Figure 6 illustrates the how thread blocks within a cluster are scheduled simultaneously on SMs within a GPC. Thread blocks within a cluster are always adjacent to each other within the grid.

Figure 6 When clusters are specified, the thread blocks in a cluster are arranged in their cluster shape within the grid. The thread blocks of a cluster are scheduled simultaneously on the SMs of a single GPC.#

1.2.2.2. Warps and SIMT#

Within a thread block, threads are organized into groups of 32 threads called warps. A warp executes the kernel code in a Single-Instruction Multiple-Threads (SIMT) paradigm. In SIMT, all threads in the warp are executing the same kernel code, but each thread may follow different branches through the code. That is, though all threads of the program execute the same code, threads do not need to follow the same execution path.

When threads are executed by a warp, they are assigned a warp lane. Warp lanes are numbered 0 to 31 and threads from a thread block are assigned to warps in a predictable fashion detailed in Hardware Multithreading.

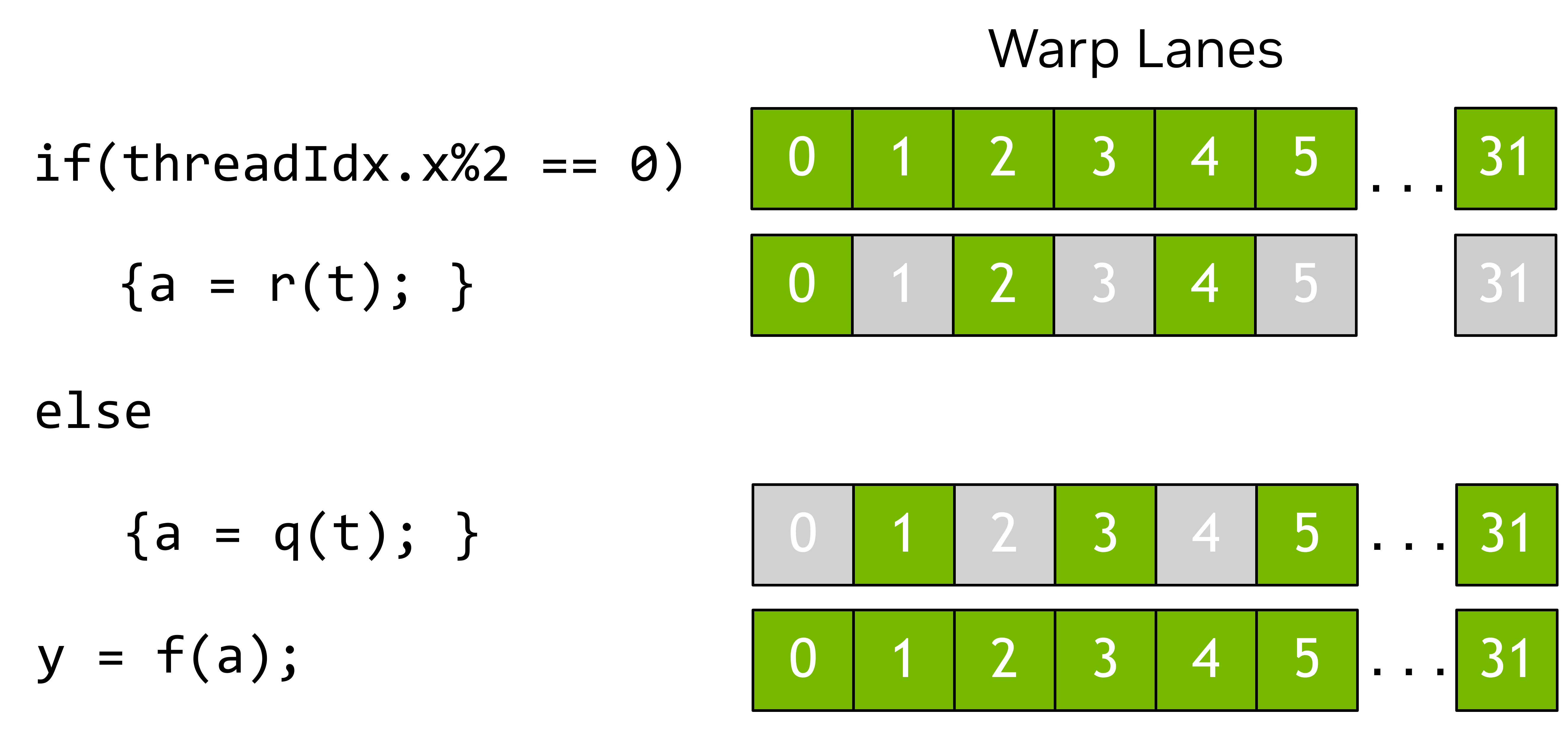

All threads in the warp execute the same instruction simultaneously. If some threads within a warp follow a control flow branch in execution while others do not, the threads which do not follow the branch will be masked off while the threads which follow the branch are executed. For example, if a conditional is only true for half the threads in a warp, the other half of the warp would be masked off while the active threads execute those instructions. This situation is illustrated in Figure 7. When different threads in a warp follow different code paths, this is sometimes called warp divergence. It follows that utilization of the GPU is maximized when threads within a warp follow the same control flow path.

Figure 7 In this example, only threads with even thread index execute the body of the if statement, the others are masked off while the body is executed.#

In the SIMT model, all threads in a warp progress through the kernel in lock step. Hardware execution may differ. See the sections on Independent Thread Execution for more information on where this distinction is important. Exploiting knowledge of how warp execution is actually mapped to real hardware is discouraged. The CUDA programming model and SIMT say that all threads in a warp progress through the code together. Hardware may optimize masked lanes in ways that are transparent to the program so long as the programming model is followed. If the program violates this model, this can result in undefined behavior that can be different in different GPU hardware.

While it is not necessary to consider warps when writing CUDA code, understanding the warp execution model is helpful in understanding concepts such as global memory coalescing and shared memory bank access patterns. Some advanced programming techniques use specialization of warps within a thread block to limit thread divergence and maximize utilization. This and other optimizations make use of the knowledge that threads are grouped into warps when executing.

One implication of warp execution is that thread blocks are best specified to have a total number of threads which is a multiple of 32. It is legal to use any number of threads, but when the total is not a multiple of 32, the last warp of the thread block will have some lanes that are unused throughout execution. This will likely lead to suboptimal functional units utilization and memory access for that warp.

SIMT is often compared to Single Instruction Multiple Data (SIMD) parallelism, but there are some important differences. In SIMD, execution follows a single control flow path, while in SIMT, each thread is allowed to follow its own control flow path. Because of this, SIMT does not have a fixed data-width like SIMD. A more detailed discussion of SIMT can be found in SIMT Execution Model.

1.2.3. GPU Memory#

In modern computing systems, efficiently utilizing memory is just as important as maximizing the use of functional units performing computations. Heterogeneous systems have multiple memory spaces, and GPUs contain various types of programmable on-chip memory in addition to caches. The following sections introduce these memory spaces in more details.

1.2.3.1. DRAM Memory in Heterogeneous Systems#

GPUs and CPUs both have directly attached DRAM chips. In systems with more than one GPU, each GPU has its own memory. From the perspective of device code, the DRAM attached to the GPU is called global memory, because it is accessible to all SMs in the GPU. This terminology does not mean it is necessarily accessible everywhere within the system. The DRAM attached to the CPU(s) is called system memory or host memory.

Like CPUs, GPUs use virtual memory addressing. On all currently-supported systems, the CPU and GPU use a single unified virtual memory space. This means that the virtual memory address range for each GPU in the system is unique and distinct from the CPU and every other GPU in the system. For a given virtual memory address, it is possible to determine whether that address is in GPU memory or system memory and, on systems with multiple GPUs, which GPU memory contains that address.

There are CUDA APIs to allocate GPU memory, CPU memory, and to copy between allocations on the CPU and GPU, within a GPU, or between GPUs in multi-GPU systems. The locality of data can be explicitly controlled when desired. Unified Memory, discussed below, allows the placement of memory to be handled automatically by the CUDA runtime or system hardware.

1.2.3.2. On-Chip Memory in GPUs#

In addition to the global memory, each GPU has some on-chip memory. Each SM has its own register file and shared memory. These memories are part of the SM and can be accessed extremely quickly from threads executing within the SM, but they are not accessible to threads running in other SMs.

The register file stores thread local variables which are usually allocated by the compiler. The shared memory is accessible by all threads within a thread block or cluster. Shared memory can be used for exchanging data between threads of a thread block or cluster.

The register file and unified data cache in an SM have finite sizes. The size of an SM’s register file, unified data cache, and how the unified data cache can be configured for L1 and shared memory balance can be found in Memory Information per Compute Capability. The register file, shared memory space, and L1 cache are shared among all threads in a thread block.

To schedule a thread block to an SM, the total number of registers needed for each thread multiplied by the number of threads in the thread block must be less than or equal to the available registers in the SM. If the number of registers required for a thread block exceeds the size of the register file, the kernel is not launchable and the number of threads in the thread block must be decreased to make the thread block launchable.

Shared memory allocations are done at the thread block level. That is, unlike register allocations which are per thread, allocations of shared memory are common to the entire thread block.

1.2.3.2.1. Caches#

In addition to programmable memories, GPUs have both L1 and L2 caches. Each SM has an L1 cache which is part of the unified data cache. A larger L2 cache is shared by all SMs within a GPU. This can be seen in the GPU block diagram in Figure 2. Each SM also has a separate constant cache, which is used to cache values in global memory that have been declared to be constant over the life of a kernel. The compiler may place kernel parameters into constant memory as well. This can improve kernel performance by allowing kernel parameters to be cached in the SM separately from the L1 data cache.

1.2.3.3. Unified Memory#

When an application allocates memory explicitly on the GPU or CPU, that memory is only accessible to code running on that device. That is, CPU memory can only be accessed from CPU code, and GPU memory can only be accessed from kernels running on the GPU[2] . CUDA APIs for copying memory between the CPU and GPU are used to explicitly copy data to the correct memory at the right time.

A CUDA feature called unified memory allows applications to make memory allocations which can be accessed from CPU or GPU. The CUDA runtime or underlying hardware enables access or relocates the data to the correct place when needed. Even with unified memory, optimal performance is attained by keeping the migration of memory to a minimum and accessing data from the processor directly attached to the memory where it resides as much as possible.

The hardware features of the system determine how access and exchange of data between memory spaces is achieved. Section Unified Memory introduces the different categories of unified memory systems. Section Unified Memory contains many more details about use and behavior of unified memory in all situations.