3.2. Advanced Kernel Programming#

This chapter will first take a deeper dive into the hardware model of NVIDIA GPUs, and then introduce some of the more advanced features available in CUDA kernel code aimed at improving kernel performance. This chapter will introduce some concepts related to thread scopes, asynchronous execution, and the associated synchronization primitives. These conceptual discussions provide a necessary foundation for some of the advanced performance features available within kernel code.

Detailed descriptions for some of these features are contained in chapters dedicated to the features in the next part of this programming guide.

Advanced synchronization primitives introduced in this chapter, are covered completely in Section 4.9 and Section 4.10.

Asynchronous data copies, including the tensor memory accelerator (TMA), are introduced in this chapter and covered completely in Section 4.11.

3.2.1. Using PTX#

Parallel Thread Execution (PTX), the virtual machine instruction set architecture (ISA) that CUDA uses to abstract hardware ISAs, was introduced in Section 1.3.3. Writing code in PTX directly is a highly advanced optimization technique that is not necessary for most developers and should be considered a tool of last resort. Nevertheless, there are situations where the fine-grained control enabled by writing PTX directly enables performance improvements in specific applications. These situations are typically in very performance-sensitive portions of an application where every fraction of a percent of performance improvement has significant benefits. All of the available PTX instructions are in the PTX ISA document.

cuda::ptx namespace

One way to use PTX directly in your code is to use the cuda::ptx namespace from libcu++. This namespace provides C++ functions that map directly to PTX instructions, simplifying their use within a C++ application. For more information, please refer to the cuda::ptx namespace documentation.

Inline PTX

Another way to include PTX in your code is to use inline PTX. This method is described in detail in the corresponding documentation. This is very similar to writing assembly code on a CPU.

3.2.2. Hardware Implementation#

A streaming multiprocessor or SM (see GPU Hardware Model) is designed to execute hundreds of threads concurrently. To manage such a large number of threads, it employs a unique parallel computing model called Single-Instruction, Multiple-Thread, or SIMT, that is described in SIMT Execution Model. The instructions are pipelined, leveraging instruction-level parallelism within a single thread, as well as extensive thread-level parallelism through simultaneous hardware multithreading as detailed in Hardware Multithreading. Unlike CPU cores, SMs issue instructions in order and do not perform branch prediction or speculative execution.

Sections SIMT Execution Model and Hardware Multithreading describe the architectural features of the SM that are common to all devices. Section Compute Capabilities provides the specifics for devices of different compute capabilities.

The NVIDIA GPU architecture uses a little-endian representation.

3.2.2.1. SIMT Execution Model#

Each SM creates, manages, schedules, and executes threads in groups of 32 parallel threads called warps. Individual threads composing a warp start together at the same program address, but they have their own instruction address counter and register state and are therefore free to branch and execute independently. The term warp originates from weaving, the first parallel thread technology. A half-warp is either the first or second half of a warp. A quarter-warp is either the first, second, third, or fourth quarter of a warp.

A warp executes one common instruction at a time, so full efficiency is realized when all 32 threads of a warp agree on their execution path. If threads of a warp diverge via a data-dependent conditional branch, the warp executes each branch path taken, disabling threads that are not on that path. Branch divergence occurs only within a warp; different warps execute independently regardless of whether they are executing common or disjoint code paths.

The SIMT architecture is akin to SIMD (Single Instruction, Multiple Data) vector organizations in that a single instruction controls multiple processing elements. A key difference is that SIMD vector organizations expose the SIMD width to the software, whereas SIMT instructions specify the execution and branching behavior of a single thread. In contrast with SIMD vector machines, SIMT enables programmers to write thread-level parallel code for independent, scalar threads, as well as data-parallel code for coordinated threads. For the purposes of correctness, the programmer can essentially ignore the SIMT behavior; however, substantial performance improvements can be realized by taking care that the code seldom requires threads in a warp to diverge. In practice, this is analogous to the role of cache lines: the cache line size can be safely ignored when designing for correctness but must be considered in the code structure when designing for peak performance. Vector architectures, on the other hand, require the software to coalesce loads into vectors and manage divergence manually.

3.2.2.1.1. Independent Thread Scheduling#

On GPUs with compute capability lower than 7.0, warps used a single program counter shared amongst all 32 threads in the warp together with an active mask specifying the active threads of the warp. As a result, threads from the same warp in divergent regions or different states of execution cannot signal each other or exchange data, and algorithms requiring fine-grained sharing of data guarded by locks or mutexes can lead to deadlock, depending on which warp the contending threads come from.

In GPUs of compute capability 7.0 and later, independent thread scheduling allows full concurrency between threads, regardless of warp. With independent thread scheduling, the GPU maintains execution state per thread, including a program counter and call stack, and can yield execution at a per-thread granularity, either to make better use of execution resources or to allow one thread to wait for data to be produced by another. A schedule optimizer determines how to group active threads from the same warp together into SIMT units. This retains the high throughput of SIMT execution as in prior NVIDIA GPUs, but with much more flexibility: threads can now diverge and reconverge at sub-warp granularity.

Independent thread scheduling can break code that relies on implicit warp-synchronous behavior from previous GPU architectures. Warp-synchronous code assumes that threads in the same warp execute in lockstep at every instruction, but the ability for threads to diverge and reconverge at sub-warp granularity makes such assumptions invalid. This can lead to a different set of threads participating in the executed code than intended. Any warp-synchronous code developed for GPUs prior to CC 7.0 (such as synchronization-free intra-warp reductions) should be revisited to ensure compatibility. Developers should explicitly synchronize such code using __syncwarp() to ensure correct behavior across all GPU generations.

Note

The threads of a warp that are participating in the current instruction are called the active threads, whereas threads not on the current instruction are inactive (disabled). Threads can be inactive for a variety of reasons including having exited earlier than other threads of their warp, having taken a different branch path than the branch path currently executed by the warp, or being the last threads of a block whose number of threads is not a multiple of the warp size.

If a non-atomic instruction executed by a warp writes to the same location in global or shared memory from more than one of the threads of the warp, the number of serialized writes that occur to that location may vary depending on the compute capability of the device. However, for all compute capabilities, which thread performs the final write is undefined.

If an atomic instruction executed by a warp reads, modifies, and writes to the same location in global memory for more than one of the threads of the warp, each read/modify/write to that location occurs and they are all serialized, but the order in which they occur is undefined.

3.2.2.2. Hardware Multithreading#

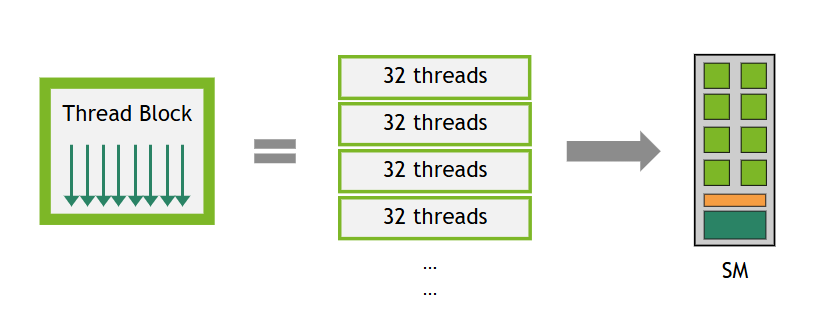

When an SM is given one or more thread blocks to execute, it partitions them into warps and each warp gets scheduled for execution by a warp scheduler. The way a block is partitioned into warps is always the same; each warp contains threads of consecutive, increasing thread IDs with the first warp containing thread 0. Thread Hierarchy describes how thread IDs relate to thread indices in the block.

The total number of warps in a block is defined as follows:

\(\text{ceil}\left( \frac{T}{W_{size}}, 1 \right)\)

T is the number of threads per block,

Wsize is the warp size, which is equal to 32,

ceil(x, y) is equal to x rounded up to the nearest multiple of y.

Figure 19 A thread block is partitioned into warps of 32 threads.#

The execution context (program counters, registers, etc.) for each warp processed by an SM is maintained on-chip throughout the warp’s lifetime. Therefore, switching between warps incurs no cost. At each instruction issue cycle, a warp scheduler selects a warp with threads ready to execute its next instruction (the active threads of the warp) and issues the instruction to those threads.

Each SM has a set of 32-bit registers that are partitioned among the warps, and a shared memory that is partitioned among the thread blocks. The number of blocks and warps that can reside and be processed concurrently on the SM for a given kernel depends on the amount of registers and shared memory used by the kernel, as well as the amount of registers and shared memory available on the SM. There are also a maximum number of resident blocks and warps per SM. These limits, as well the amount of registers and shared memory available on the SM, depend on the compute capability of the device and are specified in Compute Capabilities. If there are not enough resources available per SM to process at least one block, the kernel will fail to launch. The total number of registers and shared memory allocated for a block can be determined in several ways documented in the Occupancy section.

3.2.2.3. Asynchronous Execution Features#

Recent NVIDIA GPU generations have included asynchronous execution capabilities to allow more overlap of data movement, computation, and synchronization within the GPU. These capabilities enable certain operations invoked from GPU code to execute asynchronously to other GPU code in the same thread block. This asynchronous execution should not be confused with asynchronous CUDA APIs discussed in Section 2.3, which enable GPU kernel launches or memory operations to operate asynchronously to each other or to the CPU.

Compute capability 8.0 (The NVIDIA Ampere GPU Architecture) introduced hardware-accelerated asynchronous data copies from global to shared memory and asynchronous barriers (see NVIDIA A100 Tensor Core GPU Architecture ).

Compute capability 9.0 (The NVIDIA Hopper GPU architecture) extended the asynchronous execution features with the Tensor Memory Accelerator (TMA) unit, which can transfer large blocks of data and multidimensional tensors from global memory to shared memory and vice versa, asynchronous transaction barriers, and asynchronous matrix multiply-accumulate operations (see Hopper Architecture in Depth blog post for details.).

CUDA provides APIs which can be called by threads from device code to use these features. The asynchronous programming model defines the behavior of asynchronous operations with respect to CUDA threads.

An asynchronous operation is an operation initiated by a CUDA thread, but executed asynchronously as if by another thread, which we will refer to as an async thread. In a well-formed program, one or more CUDA threads synchronize with the asynchronous operation. The CUDA thread that initiated the asynchronous operation is not required to be among the synchronizing threads. The async thread is always associated with the CUDA thread that initiated the operation.

An asynchronous operation uses a synchronization object to signal its completion, which could be a barrier or a pipeline. These synchronization objects are explained in detail in Advanced Synchronization Primitives, and their role in performing asynchronous memory operations is demonstrated in Asynchronous Data Copies.

3.2.2.3.1. Async Thread and Async Proxy#

Asynchronous operations may access memory differently than regular operations. To distinguish between these different memory access methods, CUDA introduces the concepts of an async thread, a generic proxy, and an async proxy. Normal operations (loads and stores) go through the generic proxy. Some asynchronous instructions, such as LDGSTS and STAS/REDAS, are modeled using an async thread operating in the generic proxy. Other asynchronous instructions, such as bulk-asynchronous copies with TMA and some tensor core operations (tcgen05.*, wgmma.mma_async.*), are modeled using an async thread operating in the async proxy.

Async thread operating in generic proxy. When an asynchronous operation is initiated, it is associated with an async thread, which is different from the CUDA thread that initiated the operation. Preceding generic proxy (normal) loads and stores to the same address are guaranteed to be ordered before the asynchronous operation. However, subsequent normal loads and stores to the same address are not guaranteed to maintain their ordering, potentially incurring a race condition until the async thread completes.

Async thread operating in async proxy. When an asynchronous operation is initiated, it is associated with an async thread, which is different from the CUDA thread that initiated the operation. Prior and subsequent normal loads and stores to the same address are not guaranteed to maintain their ordering. A proxy fence is required to synchronize them across the different proxies to ensure proper memory ordering. Section Using the Tensor Memory Accelerator (TMA) demonstrates use of proxy fences to ensure correctness when performing asynchronous copies with TMA.

For more details on these concepts, see the PTX ISA documentation.

3.2.3. Thread Scopes#

CUDA threads form a Thread Hierarchy, and using this hierarchy is essential for writing both correct and performant CUDA kernels. Within this hierarchy, the visibility and synchronization scope of memory operations can vary. To account for this non-uniformity, the CUDA programming model introduces the concept of thread scopes. A thread scope defines which threads can observe a thread’s loads and stores and specifies which threads can synchronize with each other using synchronization primitives such as atomic operations and barriers. Each scope has an associated point of coherency in the memory hierarchy.

Thread scopes are exposed in CUDA PTX and are also available as extensions in the libcu++ library. The following table defines the thread scopes available:

CUDA C++ Thread Scope |

CUDA PTX Thread Scope |

Description |

Point of Coherency in Memory Hierarchy |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Memory operations are visible only to the local thread. |

– |

|

|

|

Memory operations are visible to other threads in the same thread block. |

L1 |

|

Memory operations are visible to other threads in the same thread block cluster. |

L2 |

|

|

|

Memory operations are visible to other threads in the same GPU device. |

L2 |

|

|

Memory operations are visible to other threads in the same system (CPU, other GPUs). |

L2 + connected caches |

Sections Advanced Synchronization Primitives and Asynchronous Data Copies demonstrate use of thread scopes.

3.2.4. Advanced Synchronization Primitives#

This section introduces three families of synchronization primitives:

Scoped Atomics, which pair C++ memory ordering with CUDA thread scopes to safely communicate across threads at block, cluster, device, or system scope (see Thread Scopes).

Asynchronous Barriers, which split synchronization into arrival and wait phases, and can be used to track the progress of asynchronous operations.

Pipelines, which stage work and coordinate multi-buffer producer–consumer patterns, commonly used to overlap compute with asynchronous data copies.

3.2.4.1. Scoped Atomics#

Section 5.4.5 gives an overview of atomic functions available in CUDA. In this section, we will focus on scoped atomics that support C++ standard atomic memory semantics, available through the libcu++ library or through compiler built-in functions. Scoped atomics provide the tools for efficient synchronization at the appropriate level of the CUDA thread hierarchy, enabling both correctness and performance in complex parallel algorithms.

3.2.4.1.1. Thread Scope and Memory Ordering#

Scoped atomics combine two key concepts:

Thread Scope: defines which threads can observe the effect of the atomic operation (see Thread Scopes).

Memory Ordering: defines the ordering constraints relative to other memory operations (see C++ standard atomic memory semantics).

#include <cuda/atomic>

__global__ void block_scoped_counter() {

// Shared atomic counter visible only within this block

__shared__ cuda::atomic<int, cuda::thread_scope_block> counter;

// Initialize counter (only one thread should do this)

if (threadIdx.x == 0) {

counter.store(0, cuda::memory_order_relaxed);

}

__syncthreads();

// All threads in block atomically increment

int old_value = counter.fetch_add(1, cuda::memory_order_relaxed);

// Use old_value...

}

__global__ void block_scoped_counter() {

// Shared counter visible only within this block

__shared__ int counter;

// Initialize counter (only one thread should do this)

if (threadIdx.x == 0) {

__nv_atomic_store_n(&counter, 0,

__NV_ATOMIC_RELAXED,

__NV_THREAD_SCOPE_BLOCK);

}

__syncthreads();

// All threads in block atomically increment

int old_value = __nv_atomic_fetch_add(&counter, 1,

__NV_ATOMIC_RELAXED,

__NV_THREAD_SCOPE_BLOCK);

// Use old_value...

}

This example implements a block-scoped atomic counter that demonstrates the fundamental concepts of scoped atomics:

Shared Variable: a single counter is shared among all threads in the block using

__shared__memory.Atomic Type Declaration:

cuda::atomic<int, cuda::thread_scope_block>creates an atomic integer with block-level visibility.Single Initialization: only thread 0 initializes the counter to prevent race conditions during setup.

Block Synchronization:

__syncthreads()ensures all threads see the initialized counter before proceeding.Atomic Increment: each thread atomically increments the counter and receives the previous value.

cuda::memory_order_relaxed is chosen here because we only need atomicity (indivisible read-modify-write) without ordering constraints between different memory locations. Since this is a straightforward counting operation, the order of increments doesn’t matter for correctness.

For producer-consumer patterns, acquire-release semantics ensure proper ordering:

__global__ void producer_consumer() {

__shared__ int data;

__shared__ cuda::atomic<bool, cuda::thread_scope_block> ready;

if (threadIdx.x == 0) {

// Producer: write data then signal ready

data = 42;

ready.store(true, cuda::memory_order_release); // Release ensures data write is visible

} else {

// Consumer: wait for ready signal then read data

while (!ready.load(cuda::memory_order_acquire)) { // Acquire ensures data read sees the write

// spin wait

}

int value = data;

// Process value...

}

}

__global__ void producer_consumer() {

__shared__ int data;

__shared__ bool ready; // Only ready flag needs atomic operations

if (threadIdx.x == 0) {

// Producer: write data then signal ready

data = 42;

__nv_atomic_store_n(&ready, true,

__NV_ATOMIC_RELEASE,

__NV_THREAD_SCOPE_BLOCK); // Release ensures data write is visible

} else {

// Consumer: wait for ready signal then read data

while (!__nv_atomic_load_n(&ready,

__NV_ATOMIC_ACQUIRE,

__NV_THREAD_SCOPE_BLOCK)) { // Acquire ensures data read sees the write

// spin wait

}

int value = data;

// Process value...

}

}

3.2.4.1.2. Performance Considerations#

Use the narrowest scope possible: block-scoped atomics are much faster than system-scoped atomics.

Prefer weaker orderings: use stronger orderings only when necessary for correctness.

Consider memory location: shared memory atomics are faster than global memory atomics.

3.2.4.2. Asynchronous Barriers#

An asynchronous barrier differs from a typical single-stage barrier (__syncthreads()) in that the notification by a thread that it has reached the barrier (the “arrival”) is separated from the operation of waiting for other threads to arrive at the barrier (the “wait”). This separation increases execution efficiency by allowing a thread to perform additional operations unrelated to the barrier, making more efficient use of the wait time. Asynchronous barriers can be used to implement producer-consumer patterns with CUDA threads or enable asynchronous data copies within the memory hierarchy by having the copy operation signal (“arrive on”) a barrier upon completion.

Asynchronous barriers are available on devices of compute capability 7.0 or higher. Devices of compute capability 8.0 or higher provide hardware acceleration for asynchronous barriers in shared-memory and a significant advancement in synchronization granularity, by allowing hardware-accelerated synchronization of any subset of CUDA threads within the block. Previous architectures only accelerate synchronization at a whole-warp (__syncwarp()) or whole-block (__syncthreads()) level.

The CUDA programming model provides asynchronous barriers via cuda::std::barrier, an ISO C++-conforming barrier available in the libcu++ library. In addition to implementing std::barrier, the library offers CUDA-specific extensions to select a barrier’s thread scope to improve performance and exposes a lower-level cuda::ptx API. A cuda::barrier can interoperate with cuda::ptx by using the friend function cuda::device::barrier_native_handle() to retrieve the barrier’s native handle and pass it to cuda::ptx functions. CUDA also provides a primitives API for asynchronous barriers in shared memory at thread-block scope.

The following table gives an overview of asynchronous barriers available for synchronizing at different thread scopes.

Thread Scope

Memory Location

Arrive on Barrier

Wait on Barrier

Hardware-accelerated

CUDA APIs

block

local shared memory

allowed

allowed

yes (8.0+)

cuda::barrier,cuda::ptx, primitivescluster

local shared memory

allowed

allowed

yes (9.0+)

cuda::barrier,cuda::ptxcluster

remote shared memory

allowed

not allowed

yes (9.0+)

cuda::barrier,cuda::ptxdevice

global memory

allowed

allowed

no

cuda::barriersystem

global/unified memory

allowed

allowed

no

cuda::barrier

Temporal Splitting of Synchronization

Without the asynchronous arrive-wait barriers, synchronization within a thread block is achieved using __syncthreads() or block.sync() when using Cooperative Groups.

#include <cooperative_groups.h>

__global__ void simple_sync(int iteration_count) {

auto block = cooperative_groups::this_thread_block();

for (int i = 0; i < iteration_count; ++i) {

/* code before arrive */

// Wait for all threads to arrive here.

block.sync();

/* code after wait */

}

}

Threads are blocked at the synchronization point (block.sync()) until all threads have reached the synchronization point. In addition, memory updates that happened before the synchronization point are guaranteed to be visible to all threads in the block after the synchronization point.

This pattern has three stages:

Code before the sync performs memory updates that will be read after the sync.

Synchronization point.

Code after the sync, with visibility of memory updates that happened before the sync.

Using asynchronous barriers instead, the temporally-split synchronization pattern is as follows.

#include <cuda/barrier>

#include <cooperative_groups.h>

__device__ void compute(float *data, int iteration);

__global__ void split_arrive_wait(int iteration_count, float *data)

{

using barrier_t = cuda::barrier<cuda::thread_scope_block>;

__shared__ barrier_t bar;

auto block = cooperative_groups::this_thread_block();

if (block.thread_rank() == 0)

{

// Initialize barrier with expected arrival count.

init(&bar, block.size());

}

block.sync();

for (int i = 0; i < iteration_count; ++i)

{

/* code before arrive */

// This thread arrives. Arrival does not block a thread.

barrier_t::arrival_token token = bar.arrive();

compute(data, i);

// Wait for all threads participating in the barrier to complete bar.arrive().

bar.wait(std::move(token));

/* code after wait */

}

}

|

#include <cuda/ptx>

#include <cooperative_groups.h>

__device__ void compute(float *data, int iteration);

__global__ void split_arrive_wait(int iteration_count, float *data)

{

__shared__ uint64_t bar;

auto block = cooperative_groups::this_thread_block();

if (block.thread_rank() == 0)

{

// Initialize barrier with expected arrival count.

cuda::ptx::mbarrier_init(&bar, block.size());

}

block.sync();

for (int i = 0; i < iteration_count; ++i)

{

/* code before arrive */

// This thread arrives. Arrival does not block a thread.

uint64_t token = cuda::ptx::mbarrier_arrive(&bar);

compute(data, i);

// Wait for all threads participating in the barrier to complete mbarrier_arrive().

while(!cuda::ptx::mbarrier_try_wait(&bar, token)) {}

/* code after wait */

}

}

|

#include <cuda_awbarrier_primitives.h>

#include <cooperative_groups.h>

__device__ void compute(float *data, int iteration);

__global__ void split_arrive_wait(int iteration_count, float *data)

{

__shared__ __mbarrier_t bar;

auto block = cooperative_groups::this_thread_block();

if (block.thread_rank() == 0)

{

// Initialize barrier with expected arrival count.

__mbarrier_init(&bar, block.size());

}

block.sync();

for (int i = 0; i < iteration_count; ++i)

{

/* code before arrive */

// This thread arrives. Arrival does not block a thread.

__mbarrier_token_t token = __mbarrier_arrive(&bar);

compute(data, i);

// Wait for all threads participating in the barrier to complete __mbarrier_arrive().

while(!__mbarrier_try_wait(&bar, token, 1000)) {}

/* code after wait */

}

}

|

In this pattern, the synchronization point is split into an arrive point (bar.arrive()) and a wait point (bar.wait(std::move(token))). A thread begins participating in a cuda::barrier with its first call to bar.arrive(). When a thread calls bar.wait(std::move(token)) it will be blocked until participating threads have completed bar.arrive() the expected number of times, which is the expected arrival count argument passed to init(). Memory updates that happen before participating threads’ call to bar.arrive() are guaranteed to be visible to participating threads after their call to bar.wait(std::move(token)). Note that the call to bar.arrive() does not block a thread, it can proceed with other work that does not depend upon memory updates that happen before other participating threads’ call to bar.arrive().

The arrive and wait pattern has five stages:

Code before the arrive performs memory updates that will be read after the wait.

Arrive point with implicit memory fence (i.e., equivalent to

cuda::atomic_thread_fence(cuda::memory_order_seq_cst, cuda::thread_scope_block)).Code between arrive and wait.

Wait point.

Code after the wait, with visibility of updates that were performed before the arrive.

For a comprehensive guide on how to use asynchronous barriers, see Asynchronous Barriers.

3.2.4.3. Pipelines#

The CUDA programming model provides the pipeline synchronization object as a coordination mechanism to sequence asynchronous memory copies into multiple stages, facilitating the implementation of double- or multi-buffering producer-consumer patterns. A pipeline is a double-ended queue with a head and a tail that processes work in a first-in first-out (FIFO) order. Producer threads commit work to the pipeline’s head, while consumer threads pull work from the pipeline’s tail.

Pipelines are exposed through the cuda::pipeline API in the libcu++ library, as well as through a primitives API. The following tables describe the main functionality of the two APIs.

|

Description |

|---|---|

|

Acquires an available stage in the pipeline’s internal queue. |

|

Commits the asynchronous operations issued after the |

|

Waits for completion of asynchronous operations in the oldest stage of the pipeline. |

|

Releases the oldest stage of the pipeline to the pipeline object for reuse. The released stage can be then acquired by a producer. |

Primitives API |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Request a memory copy from global to shared memory to be submitted for asynchronous evaluation. |

|

Commits the asynchronous operations issued before the call on the current stage of the pipeline. |

|

Waits for completion of asynchronous operations in all but the last N commits to the pipeline. |

The cuda::pipeline API has a richer interface with less restrictions, while the primitives API only supports tracking asynchronous copies from global memory to shared memory with specific size and alignment requirements. The primitives API provides equivalent functionality to a cuda::pipeline object with cuda::thread_scope_thread.

For detailed usage patterns and examples, see Pipelines.

3.2.5. Asynchronous Data Copies#

Efficient data movement within the memory hierarchy is fundamental to achieving high performance in GPU computing. Traditional synchronous memory operations force threads to wait idle during data transfers. GPUs inherently hide memory latency through parallelism. That is, the SM switches to execute another warp while memory operations complete. Even with this latency hiding through parallelism, it is still possible for memory latency to be a bottleneck on both memory bandwidth utilization and compute resource efficiency. To address these bottlenecks, modern GPU architectures provide hardware-accelerated asynchronous data copy mechanisms that allow memory transfers to proceed independently while threads continue executing other work.

Asynchronous data copies enable overlapping of computation with data movement, by decoupling the initiation of a memory transfer from waiting for its completion. This way, threads can perform useful work during memory latency periods, leading to improved overall throughput and resource utilization.

Note

While concepts and principles underlying this section are similar to those discussed in the earlier chapter on Asynchronous Execution, that chapter covered asynchronous execution of kernels and memory transfers such as those invoked by cudaMemcpyAsync. That can be considered asynchrony of different components of the application.

The asynchrony described in this section refers to enabling transfer of data between the GPU’s DRAM, i.e. global memory, and on-SM memory such as shared memory or tensor memory without blocking the GPU threads. This is an asynchrony within the execution of a single kernel launch.

To understand how asynchronous copies can improve performance, it is helpful to examine a common GPU computing pattern. CUDA applications often employ a copy and compute pattern that:

fetches data from global memory,

stores data to shared memory, and

performs computations on shared memory data, and potentially writes results back to global memory.

The copy phase of this pattern is typically expressed as shared[local_idx] = global[global_idx]. This global to shared memory copy is expanded by the compiler to a read from global memory into a register followed by a write to shared memory from the register.

When this pattern occurs within an iterative algorithm, each thread block needs to synchronize after the shared[local_idx] = global[global_idx] assignment, to ensure all writes to shared memory have completed before the compute phase can begin. The thread block also needs to synchronize again after the compute phase, to prevent overwriting shared memory before all threads have completed their computations. This pattern is illustrated in the following code snippet.

#include <cooperative_groups.h>

__device__ void compute(int* global_out, int const* shared_in) {

// Computes using all values of current batch from shared memory.

// Stores this thread's result back to global memory.

}

__global__ void without_async_copy(int* global_out, int const* global_in, size_t size, size_t batch_sz) {

auto grid = cooperative_groups::this_grid();

auto block = cooperative_groups::this_thread_block();

assert(size == batch_sz * grid.size()); // Exposition: input size fits batch_sz * grid_size

extern __shared__ int shared[]; // block.size() * sizeof(int) bytes

size_t local_idx = block.thread_rank();

for (size_t batch = 0; batch < batch_sz; ++batch) {

// Compute the index of the current batch for this block in global memory.

size_t block_batch_idx = block.group_index().x * block.size() + grid.size() * batch;

size_t global_idx = block_batch_idx + threadIdx.x;

shared[local_idx] = global_in[global_idx];

// Wait for all copies to complete.

block.sync();

// Compute and write result to global memory.

compute(global_out + block_batch_idx, shared);

// Wait for compute using shared memory to finish.

block.sync();

}

}

With asynchronous data copies, data movement from global memory to shared memory can be done asynchronously to enable more efficient use of the SM while waiting for data to arrive.

#include <cooperative_groups.h>

#include <cooperative_groups/memcpy_async.h>

__device__ void compute(int* global_out, int const* shared_in) {

// Computes using all values of current batch from shared memory.

// Stores this thread's result back to global memory.

}

__global__ void with_async_copy(int* global_out, int const* global_in, size_t size, size_t batch_sz) {

auto grid = cooperative_groups::this_grid();

auto block = cooperative_groups::this_thread_block();

assert(size == batch_sz * grid.size()); // Exposition: input size fits batch_sz * grid_size

extern __shared__ int shared[]; // block.size() * sizeof(int) bytes

size_t local_idx = block.thread_rank();

for (size_t batch = 0; batch < batch_sz; ++batch) {

// Compute the index of the current batch for this block in global memory.

size_t block_batch_idx = block.group_index().x * block.size() + grid.size() * batch;

// Whole thread-group cooperatively copies whole batch to shared memory.

cooperative_groups::memcpy_async(block, shared, global_in + block_batch_idx, block.size());

// Compute on different data while waiting.

// Wait for all copies to complete.

cooperative_groups::wait(block);

// Compute and write result to global memory.

compute(global_out + block_batch_idx, shared);

// Wait for compute using shared memory to finish.

block.sync();

}

}

The cooperative_groups::memcpy_async function copies block.size() elements from global memory to the shared data. This operation happens as-if performed by another thread, which synchronizes with the current thread’s call to cooperative_groups::wait after the copy has completed. Until the copy operation completes, modifying the global data or reading or writing the shared data introduces a data race.

This example illustrates the fundamental concept behind all asynchronous copy operations: they decouple memory transfer initiation from completion, allowing threads to perform other work while data moves in the background. The CUDA programming model provides several APIs to access these capabilities, including memcpy_async functions available in Cooperative Groups and the libcu++ library, as well as lower-level cuda::ptx and primitives APIs. These APIs share similar semantics: they copy objects from source to destination as-if performed by another thread which, on completion of the copy, can be synchronized using different completion mechanisms.

Modern GPU architectures provide multiple hardware mechanisms for asynchronous data movement.

LDGSTS (compute capability 8.0+) allows for efficient small-scale asynchronous transfers from global to shared memory.

The tensor memory accelerator (TMA, compute capability 9.0+) extends these capabilities, providing bulk-asynchronous copy operations optimized for large multi-dimensional data transfers

STAS instructions (compute capability 9.0+) enable small-scale asynchronous transfers from registers to distributed shared memory within a cluster.

These mechanisms support different data paths, transfer sizes, and alignment requirements, allowing developers to choose the most appropriate approach for their specific data access patterns. The following table gives an overview of the supported data paths for asynchronous copies within the GPU.

Direction |

Copy Mechanism |

||

|---|---|---|---|

Source |

Destination |

Asynchronous Copy |

Bulk-Asynchronous Copy |

global |

global |

||

shared::cta |

global |

supported (TMA, 9.0+) |

|

global |

shared::cta |

supported (LDGSTS, 8.0+) |

supported (TMA, 9.0+) |

global |

shared::cluster |

supported (TMA, 9.0+) |

|

shared::cluster |

shared::cta |

supported (TMA, 9.0+) |

|

shared::cta |

shared::cta |

||

registers |

shared::cluster |

supported (STAS, 9.0+) |

|

Sections Using LDGSTS, Using the Tensor Memory Accelerator (TMA) and Using STAS will go into more details about each mechanism.