5.5. Floating-Point Computation#

5.5.1. Floating-Point Introduction#

Since the adoption of the IEEE-754 Standard for Binary Floating-Point Arithmetic in 1985, virtually all mainstream computing systems, including NVIDIA’s CUDA architectures, have implemented the standard. The IEEE-754 standard specifies how the results of floating-point arithmetic should be approximated.

To get accurate results and achieve the highest performance with the required precision, it is important to consider many aspects of floating-point behavior. This is particularly important in a heterogeneous computing environment where operations are performed on different types of hardware.

The following sections review the basic properties of floating-point computation and cover Fused Multiply-Add (FMA) operations and the dot product. These examples illustrate how different implementation choices affect accuracy.

5.5.1.1. Floating-Point Format#

Floating-point format and functionality are defined in the IEEE-754 Standard.

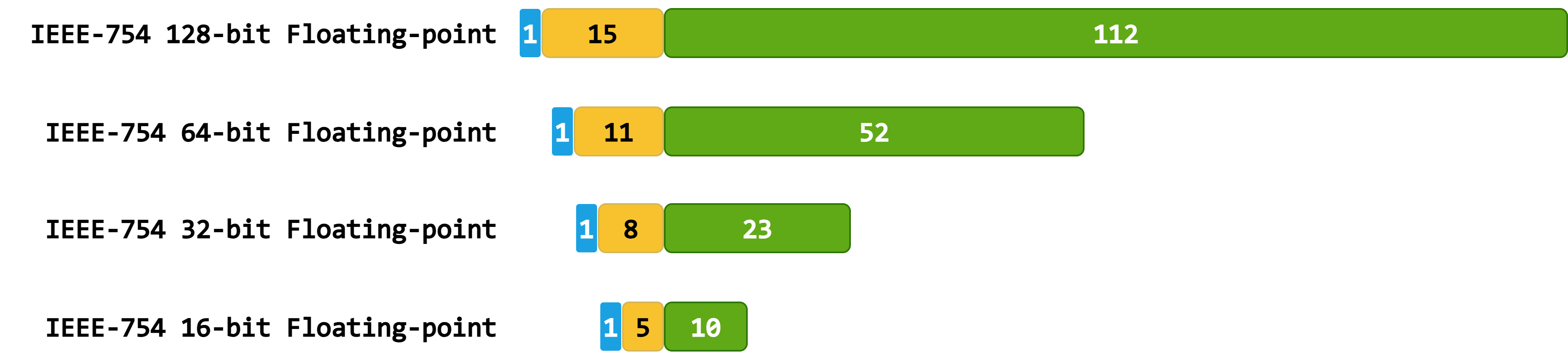

The standard mandates that binary floating-point data be encoded on three fields:

Sign: one bit to indicate a positive or negative number.

Exponent: encodes the exponent offset by a numeric bias in base 2.

Significand (also called mantissa or fraction): encodes the fractional value of the number.

The latest IEEE-754 standard defines the encodings and properties of the following binary formats:

16-bit, also known as half-precision, corresponding to the

__halfdata type in CUDA.32-bit, also known as single-precision, corresponding to the

floatdata type in C, C++, and CUDA.64-bit, also known as double-precision, corresponding to the

doubledata type in C, C++, and CUDA.128-bit, also known as quad-precision, corresponding to the

__float128or_Float128data types in CUDA.

These types have the following bit lengths:

The numeric value associated with floating-point encoding for normal values is computed as follows:

for subnormal values, the leading 1 in the formula is absent.

7 + 127 = 134 = 10000110 for float and 7 + 1023 = 1030 = 10000111110 for double. The mantissa 0.5 = 2^-1 is represented by a binary value with 1 in the first position. The binary encoding of \(-192\) in single-precision and double-precision is shown in the following figure:

Since the fraction field uses a limited number of bits, not all real numbers can be represented exactly. For instance, the binary representation of the mathematical value of the fraction \(2 / 3\) is 0.10101010..., which has an infinite number of bits after the binary point. Therefore, \(2 / 3\) must be rounded before it can be represented as a floating-point number with limited precision. The rounding rules and modes are specified in IEEE-754. The most frequently used mode is round-to-nearest-or-even, abbreviated round-to-nearest.

5.5.1.2. Normal and Subnormal Values#

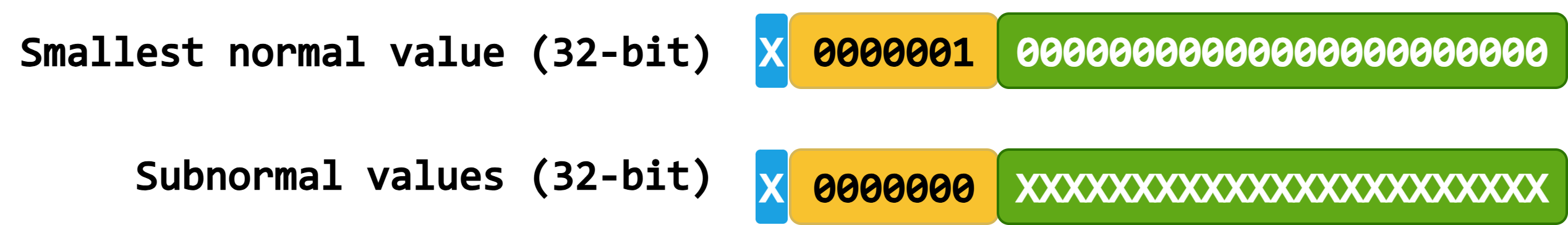

Any floating-point value that can be represented with at least one bit set in the exponent is called normal.

An important aspect of floating-point normal values is the wide gap between the smallest representable non-zero floating-point number, FLT_MIN, and zero. This gap is much wider than the gap between FLT_MIN and the second-smallest representable non-zero floating-point number.

Floating-point subnormal numbers, also called denormals, were introduced to address this issue. A subnormal floating-point value is represented with all bits in the exponent set to zero and at least one bit set in the significand. Subnormals are a required part of the IEEE-754 floating-point standard.

Subnormal numbers allow for a gradual loss of precision as an alternative to sudden rounding toward zero. However, subnormal numbers are computationally more expensive. Therefore, applications that don’t require strict accuracy may choose to avoid them to improve performance. The nvcc compiler allows disabling subnormal numbers by setting the -ftz=true option (flush-to-zero), which is also included in --use_fast_math.

A simplified visualization of the encoding of the smallest normal value and subnormal values in single-precision is shown in the following figure:

where X represents both 0 and 1.

5.5.1.3. Special Values#

The IEEE-754 standard defines three special values for floating-point numbers:

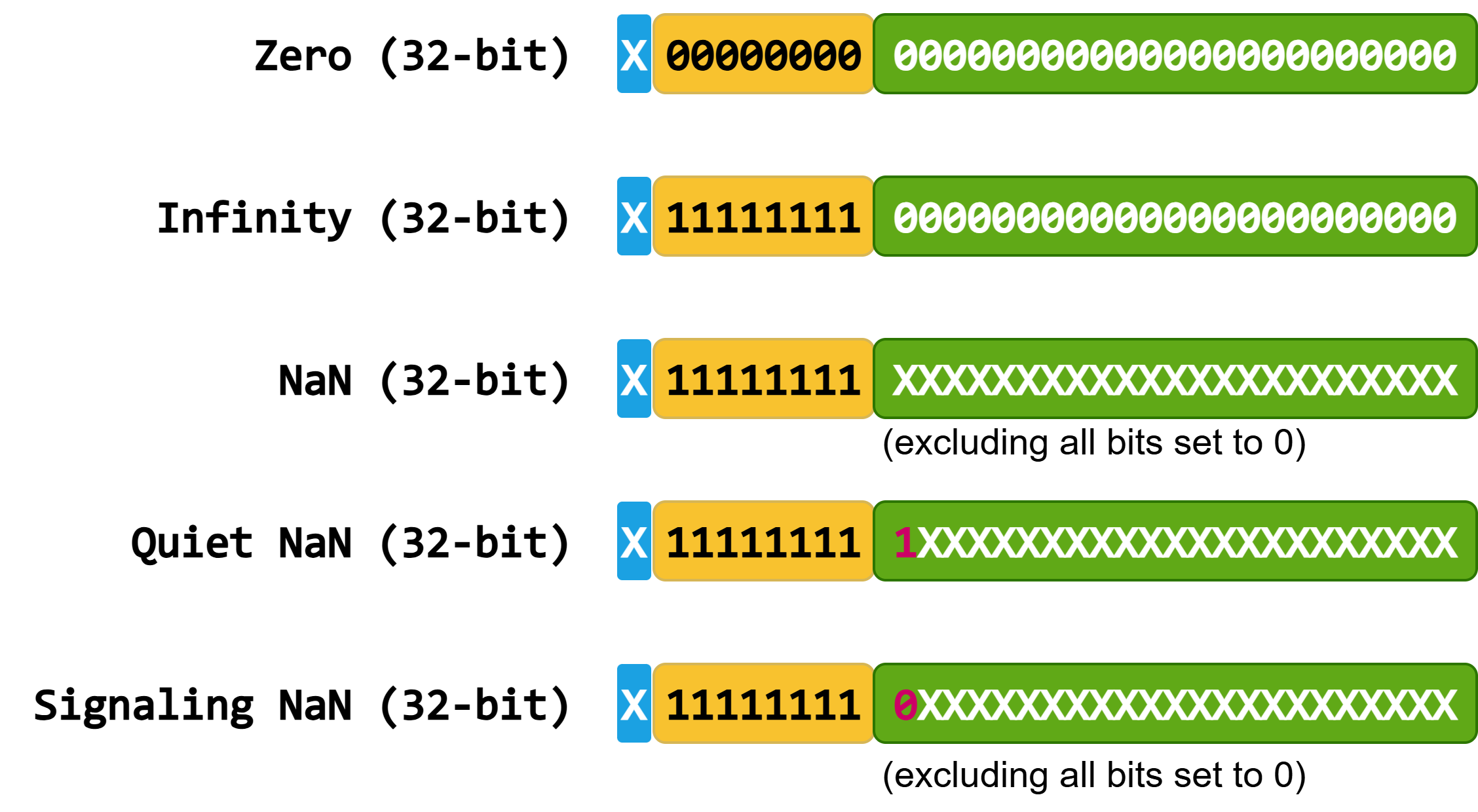

Zero:

Mathematical zero.

Note that there are two possible representations of floating-point zero:

+0and-0. This differs from the representation of integer zero.+0 == -0evaluates totrue.0is encoded with all bits set to0in the exponent and significand.

Infinity:

Floating-point numbers behave according to saturation arithmetic, in which operations that overflow the representable range result in

+Infinityor-Infinity.Infinity is encoded with all bits in the exponent set to

1and all bits in the significand set to0. There are exactly two encodings for infinity values.Any arithmetic operation that applies a finite number to infinity will result in infinity, except for division by zero and multiplication by zero, which result in NaN.

Not-a-Number (NaN):

NaN is a special symbol that represents an undefined or non-representable value. Common examples are

0.0 / 0.0,sqrt(-1.0), or+Inf - Inf.NaN is encoded with all bits in the exponent set to

1and any bit pattern in the significand, except for all bits set to 0. There are \(2^{\mathrm{mantissa} + 1} - 2\) possible encodings.Any arithmetic operation involving a NaN will result in NaN.

Any comparison operation involving a NaN will result in

false, includingNaN == NaN(non-reflexive).NaNs are provided in two forms:

Quiet NaNs

qNaNare used to propagate errors resulting from invalid operations or values. Invalid arithmetic operations generally produce a quiet NaN. They are encoded with the most significant bit of the significand set to1.Signaling NaNs

sNaNare designed to raise an invalid-operation exception. Signaling NaNs are generally explicitly created. They are encoded with the most significant bit of the significand set to0.The exact bit patterns for Quiet and Signaling NaNs are implementation-defined. CUDA provides the cuda::std::numeric_limits<T>::quiet_NaN and cuda::std::numeric_limits<T>::signaling_NaN constants to get their special values.

A simplified visualization of the encodings of special values is shown in the following figure:

where X represents both 0 and 1.

5.5.1.4. Associativity#

It is important to note that the rules and properties of mathematical arithmetic do not directly apply to floating-point arithmetic due to its limited precision. The example below shows single-precision values A, B, and C and the exact mathematical value of their sum computed using different associativity.

Mathematically, \((A + B) + C\) is equal to \(A + (B + C)\).

Let \(\mathrm{rn}(x)\) denote one rounding step on \(x\). Performing the same computations in single-precision floating-point arithmetic in round-to-nearest mode according to IEEE-754, we obtain:

For reference, the exact mathematical results are also computed above. The results computed according to IEEE-754 differ from the exact mathematical results. Additionally, the results corresponding to the sums \(\mathrm{rn}(\mathrm{rn}(A + B) + C)\) and \(\mathrm{rn}(A + \mathrm{rn}(B + C))\) differ from each other. In this case, \(\mathrm{rn}(A + \mathrm{rn}(B + C))\) is closer to the correct mathematical result than \(\mathrm{rn}(\mathrm{rn}(A + B) + C)\).

This example shows that seemingly identical computations can produce different results, even when all basic operations comply with IEEE-754.

5.5.1.5. Fused Multiply-Add (FMA)#

The Fused Multiply-Add (FMA) operation computes the result with only one rounding step. Without the FMA, the result would require two rounding steps: one for multiplication and one for addition. Because the FMA uses only one rounding step, it produces a more accurate result.

The Fused Multiply-Add operation can affect the propagation of NaNs differently than two separate operations. However, FMA NaN handling is not universally identical across all targets. Different implementations with multiple NaN operands may prefer a quiet NaN or propagate one operand’s payload. Additionally, IEEE-754 does not strictly mandate a deterministic payload selection order when multiple NaN operands are present. NaNs may also occur in intermediate computations, for example, \(\infty \times 0 + 1\) or \(1 \times \infty - \infty\), resulting in an implementation-defined NaN payload.

For clarity, first consider an example using decimal arithmetic to illustrate how the FMA operation works. We will compute \(x^2 - 1\) using five total digits of precision, with four digits after the decimal point.

For \(x = 1.0008\), the correct mathematical result is \(x^2 - 1 = 1.60064 \times 10^{-4}\). The closest number using only four digits after the decimal point is \(1.6006 \times 10^{-4}\).

The Fused Multiply-Add operation achieves the correct result using only one rounding step \(\mathrm{rn}(x \times x - 1) = 1.6006 \times 10^{-4}\).

The alternative is to compute the multiply and add steps separately. \(x^2 = 1.00160064\) translates to \(\mathrm{rn}(x \times x) = 1.0016\). The final result is \(\mathrm{rn}(\mathrm{rn}(x \times x) -1) = 1.6000 \times 10^{-4}\).

Rounding the multiply and add separately yields a result that is off by \(0.00064\). The corresponding FMA computation is wrong by only \(0.00004\) and its result is closest to the correct mathematical answer. The results are summarized below:

Below is another example, using binary single precision values:

Computing multiplication and addition separately results in the loss of all bits of precision, yielding \(0\).

Computing the FMA, on the other hand, provides a result equal to the mathematical value.

Fused multiply-add helps prevent loss of precision during subtractive cancellation. Subtractive cancellation occurs when quantities of similar magnitude with opposite signs are added. In this case, many of the leading bits cancel out, resulting in fewer meaningful bits. The fused multiply-add computes a double-width product during multiplication. Thus, even if subtractive cancellation occurs during addition, there are enough valid bits remaining in the product to yield a precise result.

Fused Multiply-Add Support in CUDA:

CUDA provides the Fused Multiply-Add operation in several ways for both float and double data types:

x * y + zwhen compiled with the flags-fmad=trueor--use_fast_math.fma(x, y, z)andfmaf(x, y, z)C Standard Library functions.__fmaf_[rd, rn, ru, rz],__fmaf_ieee_[rd, rn, ru, rz], and__fma_[rd, rn, ru, rz]CUDA mathematical intrinsic functions.cuda::std::fma(x, y, z)andcuda::std::fmaf(x, y, z)CUDA C++ Standard Library functions.

Fused Multiply-Add Support on Host Platforms:

Whether to use the fused operation depends on the availability of the operation on the platform and how the code is compiled. It is important to understand the host platform’s support for Fused Multiply-Add when comparing CPU and GPU results.

Compiler flags and Fused Multiply-Add hardware support:

-mfmawith GCC and Clang,-Mfmawith NVC++, and/fp:contractwith Microsoft Visual Studio.x86 platforms with the AVX2 ISA, for example, code compiled with the

-mavx2flag using GCC or Clang, and/arch:AVX2with Microsoft Visual Studio.Arm64 (AArch64) platforms with Advanced SIMD (Neon) ISA.

fma(x, y, z)andfmaf(x, y, z)C Standard Library functions.std::fma(x, y, z)andstd::fmaf(x, y, z)C++ Standard Library functions.cuda::std::fma(x, y, z)andcuda::std::fmaf(x, y, z)CUDA C++ Standard Library functions.

5.5.1.6. Dot Product Example#

Consider the problem of finding the dot product of two short vectors \(\overrightarrow{a}\) and \(\overrightarrow{b}\) both with four elements.

Although this operation is easy to write down mathematically, implementing it in software involves several alternatives that could lead to slightly different results. All of the strategies presented here use operations that are fully compliant with IEEE-754.

Example Algorithm 1: The simplest way to compute the dot product is to use a sequential sum of products, keeping the multiplications and additions separate.

The final result can be represented as \(((((a_1 \times b_1) + (a_2 \times b_2)) + (a_3 \times b_3)) + (a_4 \times b_4))\).

Example Algorithm 2: Compute the dot product sequentially using fused multiply-add.

The final result can be represented as \((a_4 \times b_4) + ((a_3 \times b_3) + ((a_2 \times b_2) + (a_1 \times b_1 + 0)))\).

Example Algorithm 3: Compute the dot product using a divide-and-conquer strategy. First, we find the dot products of the first and second halves of the vectors. Then, we combine these results using addition. This algorithm is called the “parallel algorithm” because the two subproblems can be computed in parallel since they are independent of each other. However, the algorithm does not require a parallel implementation; it can be implemented with a single thread.

The final result can be represented as \(((a_1 \times b_1) + (a_2 \times b_2)) + ((a_3 \times b_3) + (a_4 \times b_4))\).

5.5.1.7. Rounding#

The IEEE-754 standard requires support for several operations. These include arithmetic operations such as addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, square root, fused multiply-add, finding the remainder, conversion, scaling, sign, and comparison operations. The results of these operations are guaranteed to be consistent across all implementations of the standard for a given format and rounding mode.

Rounding Modes

The IEEE-754 standard defines four rounding modes: round-to-nearest, round towards positive, round towards negative, and round towards zero. CUDA supports all four modes. By default, operations use round-to-nearest. Intrinsic mathematical functions can be used to select other rounding modes for individual operations.

Rounding Mode |

Interpretation |

|---|---|

|

Round to nearest, ties to even |

|

Round towards zero |

|

Round towards \(\infty\) |

|

Round towards \(-\infty\) |

5.5.1.8. Notes on Host/Device Computation Accuracy#

The accuracy of a floating-point computation result is affected by several factors. This section summarizes important considerations for achieving reliable results in floating-point computations. Some of these aspects have been described in greater detail in previous sections.

These aspects are also important when comparing the results between CPU and GPU. Differences between host and device execution must be interpreted carefully. The presence of differences does not necessarily mean the GPU’s result is incorrect or that there is a problem with the GPU.

Associativity:

Floating-point addition and multiplication in finite precision are not associative because they often result in mathematical values that cannot be directly represented in the target format, requiring rounding. The order in which these operations are evaluated affects how rounding errors accumulate and can significantly alter the final result.

Fused Multiply-Add:

Fused Multiply-Add computes \(a \times b + c\) in a single operation, resulting in greater accuracy and a faster execution time. The accuracy of the final result can be affected by its use. Fused Multiply-Add relies on hardware support and can be enabled either explicitly by calling the related function or implicitly through compiler optimization flags.

Precision:

Increasing the floating-point precision can potentially improve the accuracy of the results. Higher precision reduces loss of significance and enables the representation of a wider range of values. However, higher precision types have lower throughput and consumes more registers. Additionally, using them to explicitly store input and output increases memory usage and data movement.

Compiler Flags and Optimizations:

All major compilers provide a variety of optimization flags to control the behavior of floating-point operations.

The highest optimization level for GCC (

-O3), Clang (-O3), nvcc (-O3), and Microsoft Visual Studio (/O2) does not affect floating-point semantics. However, inlining, loop unrolling, vectorization, and common subexpression elimination could affect the results. The NVC++ compiler also requires the flags-Kieee -Mnofmafor IEEE-754-compliant semantics.Refer to the GCC, Clang, Microsoft Visual Studio Compiler, nvc++, and Arm C/C++ compiler documentation for detailed information about options that affect floating-point behavior.

Library Implementations:

Functions defined outside the IEEE-754 standard are not guaranteed to be correctly rounded and depend on implementation-defined behavior. Therefore, the results may differ across different platforms, including between host, device, and different device architectures.

Deterministic Results:

A deterministic result refers to computing the same bit-wise numerical outputs every time when run with the same inputs under the same specified conditions. Such conditions include:

Hardware dependencies, such as execution on the same CPU processor or GPU device.

Compiler aspects, such as the version of the compiler and the compiler flags.

Run-time conditions that affect the computation, such as rounding mode or environment variables.

Identical inputs to the computation.

Thread configuration, including the number of threads involved in the computation and their organization, for example block and grid size.

The ordering of arithmetic atomic operations depends on hardware scheduling which can vary between runs.

Taking Advantage of the CUDA Libraries:

The CUDA Math Libraries, C Standard Library Mathematical functions, and C++ Standard Library Mathematical functions are designed to boost developer productivity for common functionalities, particularly for floating-point math and numerics-intensive routines. These functionalities provide a consistent high-level interface, are optimized, and are widely tested across platforms and edge cases. Users are encouraged to take full advantage of these libraries and avoid tedious manual reimplementations.

5.5.2. Floating-Point Data Types#

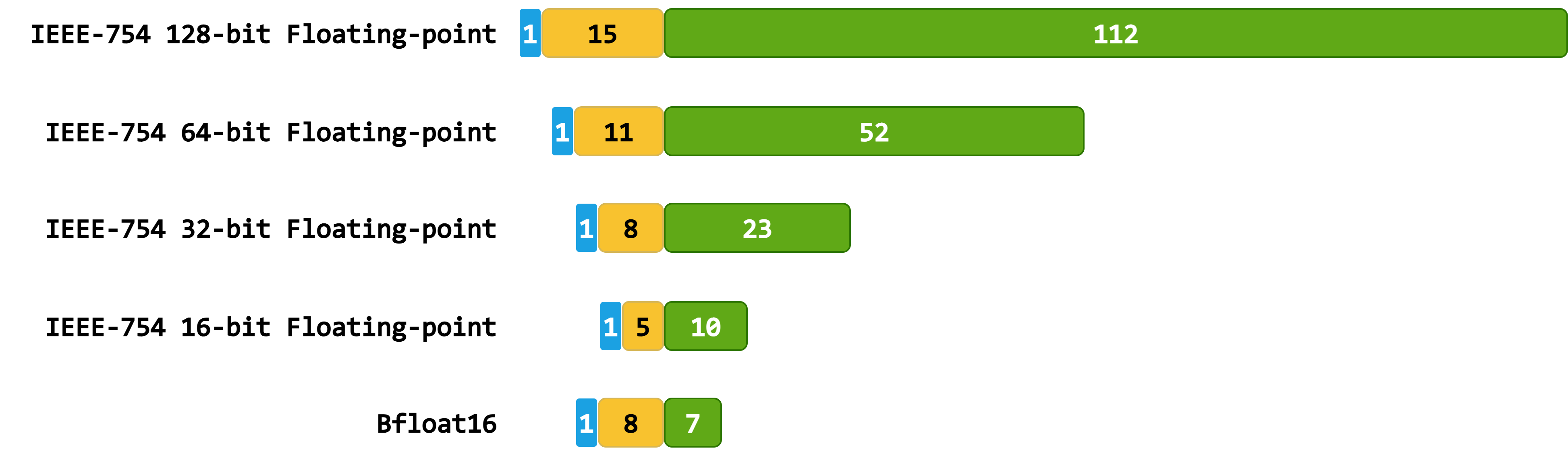

CUDA supports the Bfloat16, half-, single-, double-, and quad-precision floating-point data types. The following table summarizes the supported floating-point data types in CUDA and their requirements.

Precision / Name |

Data Type |

IEEE-754 |

Header / Built-in |

Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Bfloat16 |

|

❌ |

|

Compute Capability 8.0 or higher. |

Half Precision |

|

✅ |

|

|

Single Precision |

|

✅ |

Built-in |

|

Double Precision |

|

✅ |

Built-in |

|

Quad Precision |

|

✅ |

Built-in

|

Host compiler support and Compute Capability 10.0 or higher. The C or C++ spelling, |

CUDA also supports TensorFloat-32 (TF32), microscaling (MX) floating-point types, and other lower precision numerical formats that are not intended for general-purpose computation, but rather for specialized purposes involving tensor cores. These include 4-, 6-, and 8-bit floating-point types. See the CUDA Math API for more details.

The following figure reports the mantissa and exponent sizes of the supported floating-point data types.

The following table reports the ranges of the supported floating-point data types.

Precision / Name |

Largest Value |

Smallest Positive Value |

Smallest Positive Denormal |

Epsilon |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Bfloat16 |

\(\approx 2^{128}\) |

\(\approx 3.39 \cdot 10^{38}\) |

\(2^{-126}\) |

\(\approx 1.18 \cdot 10^{-38}\) |

\(2^{-133}\) |

\(2^{-7}\) |

Half Precision |

\(\approx 2^{16}\) |

\(65504\) |

\(2^{-14}\) |

\(\approx 6.1 \cdot 10^{-5}\) |

\(2^{-24}\) |

\(2^{-10}\) |

Single Precision |

\(\approx 2^{128}\) |

\(\approx 3.39 \cdot 10^{38}\) |

\(2^{-126}\) |

\(\approx 1.18 \cdot 10^{-38}\) |

\(2^{-149}\) |

\(2^{-23}\) |

Double Precision |

\(\approx 2^{1024}\) |

\(\approx 1.8 \cdot 10^{308}\) |

\(2^{-1022}\) |

\(\approx 2.22 \cdot 10^{-308}\) |

\(2^{-1074}\) |

\(2^{-52}\) |

Quad Precision |

\(\approx 2^{16384}\) |

\(\approx 1.19 \cdot 10^{4932}\) |

\(2^{-16382}\) |

\(\approx 3.36 \cdot 10^{-4032}\) |

\(2^{-16494}\) |

\(2^{-112}\) |

Hint

The CUDA C++ Standard Library provides cuda::std::numeric_limits in the <cuda/std/limits> header to query the properties and the ranges of the supported floating-point types, including microscaling formats (MX). See the C++ reference for the list of queryable properties.

Complex numbers support:

The CUDA C++ Standard Library supports complex numbers with the cuda::std::complex type in the

<cuda/std/complex>header. See also the libcu++ documentation for more details.CUDA also provides basic support for complex numbers with the

cuComplexandcuDoubleComplextypes in thecuComplex.hheader.

5.5.3. CUDA and IEEE-754 Compliance#

All GPU devices follow the IEEE 754-2019 standard for binary floating-point arithmetic with the following limitations:

There is no dynamically configurable rounding mode; however, most of the operations support multiple constant IEEE rounding modes, selectable via specifically named device intrinsics functions.

There is no mechanism to detect floating-point exceptions, so all operations behave as if IEEE-754 exceptions are always masked. If there is an exceptional event, the default masked response defined by IEEE-754 is delivered. For this reason, although signaling NaN

SNaNencodings are supported, they are not signaling and are handled as quiet exceptions.Floating-point operations may alter the bit patterns of input NaN payloads. Operations such as absolute value and negation may also not comply with the IEEE 754 requirement, which could result in the sign of a NaN being updated in an implementation-defined manner.

To maximize the portability of results, users are recommended to use the default settings of the nvcc compiler’s floating-point options: -ftz=false, -prec-div=true, and -prec-sqrt=true, and not use the --use_fast_math option. Note that floating-point expression re-associations and contractions are allowed by default, similarly to the --fmad=true option. See also the nvcc User Manual for a detailed description of these compilation flags.

The IEEE-754 and C/C++ language standards do not explicitly address the conversion of a floating-point value to an integer value in cases where the rounded-to-integer value falls outside the range of the target integer format. The clamping behavior to the range of GPU devices is delineated in the PTX ISA conversion instructions section. However, compiler optimizations may leverage the unspecified behavior clause when out-of-range conversion is not invoked directly via a PTX instruction, consequently resulting in undefined behavior and an invalid CUDA program. The CUDA Math documentation issues warnings to users on a per-function/intrinsic basis. For instance, consider the __double2int_rz() instruction. This may differ from how host compilers and library implementations behave.

Atomic Functions Denormals Behavior:

Atomic operations have the following behavior regarding floating-point denormals, regardless of the setting of the compiler flag -ftz:

Atomic single-precision floating-point adds on global memory always operate in flush-to-zero mode, namely behave equivalent to PTX

add.rn.ftz.f32semantic.Atomic single-precision floating-point adds on shared memory always operate with denormal support, namely behave equivalent to PTX

add.rn.f32semantic.

5.5.4. CUDA and C/C++ Compliance#

Floating-Point Exceptions:

Unlike the host implementation, the mathematical operators and functions supported in device code do not set the global errno variable nor report floating-point exceptions to indicate errors. Thus, if error diagnostic mechanisms are required, users should implement additional input and output screening for the functions.

Undefined Behavior with Floating-Point Operations:

Common conditions of undefined behavior for mathematical operations include:

Invalid arguments to mathematical operators and functions:

Using an uninitialized floating-point variable.

Using a floating-point variable outside its lifetime.

Signed integer overflow.

Dereferencing an invalid pointer.

Floating-point specific undefined behavior:

Converting a floating-point value to an integer type for which the result is not representable is undefined behavior. This also includes NaN and infinity.

Users are responsible for ensuring the validity of a CUDA program. Invalid arguments may result in undefined behavior and be subject to compiler optimizations.

Contrary to integer division by zero, floating-point division by zero is not undefined behavior and not subject to compiler optimizations; rather, it is implementation-specific behavior. C++ implementations that conform to IEC-60559 (IEEE-754), including CUDA, produce infinity. Note that invalid floating-point operations produce NaN and should not be misinterpreted as undefined behavior. Examples include zero divided by zero and infinity divided by infinity.

Floating-Point Literals Portability:

Both C and C++ allow for the representation of floating-point values in either decimal or hexadecimal notation. Hexadecimal floating-point literals, which are supported in C99 and C++17, denote a real value in scientific notation that can be precisely expressed in base-2. However, this does not guarantee that the literal will map to an actual value stored in a target variable (see the next paragraph). Conversely, a decimal floating-point literal may represent a numeric value that cannot be expressed in base-2.

According to the C++ standard rules, hexadecimal and decimal floating-point literals are rounded to the nearest representable value, larger or smaller, chosen in an implementation-defined manner. This rounding behavior may differ between the host and the device.

float f1 = 0.5f; // 0.5, '0.5f' is a decimal floating-point literal

float f2 = 0x1p-1f; // 0.5, '0x1p-1f' is a hexadecimal floating-point literal

float f3 = 0.1f;

// f1, f2 are represented as 0 01111110 00000000000000000000000

// f3 is represented as 0 01111011 10011001100110011001101

The run-time and compile-time evaluations of the same floating-point expression are subject to the following portability issues:

The run-time evaluation of a floating-point expression may be affected by the selected rounding mode, floating-point contraction (FMA) and reassociation compiler settings, as well as floating-point exceptions. Note that CUDA does not support floating-point exceptions and the rounding mode is always round-to-nearest-ties-to-even.

The compiler may use a higher-precision internal representation for constant expressions.

The compiler may perform optimizations, such as constant folding, constant propagation, and common subexpression elimination, which can lead to a different final value or comparison result.

C Standard Math Library Notes:

The host implementations of common mathematical functions are mapped to C Standard Math Library functions in a platform-specific way. These functions are provided by the host compiler and the respective host libm, if available.

Functions not available from the host compilers are implemented in the

crt/math_functions.hheader file. For example,erfinv()is implemented there.Less common functions, such as

rhypot()andcyl_bessel_i0(), are only available in the device code.

As previously mentioned, the host and device implementations of mathematical functions are independent. For more details on the behavior of these functions, please refer to the host implementation’s documentation.

5.5.5. Floating-Point Functionality Exposure#

The mathematical functions supported by CUDA are exposed through the following methods:

Built-in C/C++ language arithmetic operators:

x + y,x - y,x * y,x / y,x++,x--,+=,-=,*=,/=.Support single-, double-, and quad-precision types,

float,double, and__float128/_Float128respectively.__halfand__nv_bfloat16types are also supported by including the<cuda_fp16.h>and<cuda_bf16.h>headers, respectively.__float128/_Float128type support relies on the host compiler and device compute capability, see the Supported Floating-Point Types table.

They are available in both host and device code.

Their behavior is affected by the

nvccoptimization flags.

CUDA C++ Standard Library Mathematical functions:

Expose the full set of C++

<cmath>header functions exposed through the<cuda/std/cmath>header and thecuda::std::namespace.Support IEEE-754 standard floating-point types,

__half,float,double,__float128, as well as Bfloat16__nv_bfloat16.__float128support relies on the host compiler and device compute capability, see the Supported Floating-Point Types table.

They are available in both host and device code.

They often rely on the CUDA Math API functions. Therefore, there could be different levels of accuracy between the host and device code.

Their behavior is affected by the

nvccoptimization flags.A subset of functionalities is also supported on constant expressions, such as

constexprfunctions, in accordance with the C++23 and C++26 standard specifications.

CUDA C Standard Library Mathematical functions (CUDA Math API):

Expose a subset of the C

<math.h>header functions.Support single and double-precision types,

floatanddoublerespectively.They are available in both host and device code.

They don’t require additional headers.

Their behavior is affected by the

nvccoptimization flags.

A subset of the

<math.h>header functionalities is also available for__half,__nv_bfloat16, and__float128/_Float128types. These functions have names that resemble those of the C Standard Library.__halfand__nv_bfloat16types require the<cuda_fp16.h>and<cuda_bf16.h>headers, respectively. Their host and device code availability is defined on a per-function basis.__float128/_Float128type support relies on the host compiler and device compute capability, see the Supported Floating-Point Types table. The related functions require thecrt/device_fp128_functions.hheader and they are only available in device code.

They can have a different accuracy between host and device code.

Non-standard CUDA Mathematical functions (CUDA Math API):

Expose mathematical functionalities that are not part of the C/C++ Standard Library.

Mainly support single- and double-precision types,

floatanddoublerespectively.Their host and device code availability is defined on a per-function basis.

They don’t require additional headers.

They can have a different accuracy between host and device code.

__nv_bfloat16,__half,__float128/_Float128are supported for a limited set of functions.__halfand__nv_bfloat16types require the<cuda_fp16.h>and<cuda_bf16.h>headers, respectively.__float128/_Float128type support relies on the host compiler and device compute capability, see the Supported Floating-Point Types table. The related functions require thecrt/device_fp128_functions.hheader.They are only available in device code.

Their behavior is affected by the

nvccoptimization flags.

Intrinsic Mathematical functions (CUDA Math API):

Support single- and double-precision types,

floatanddoublerespectively.They are only available in device code.

They are faster but less accurate than the respective CUDA Math API functions.

Their behavior is not affected by the

nvccfloating-point optimization flags-prec-div=false,-prec-sqrt=false, and-fmad=true. The only exception is-ftz=true, which is also included in-use_fast_math.

Functionality |

Supported Types |

Host |

Device |

Affected by Floating-Point Optimization Flags |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

✅ |

✅ |

✅ |

|

|

✅ |

✅ |

✅ |

|

|

||||

|

✅ |

✅ |

✅ |

|

|

On a per-function basis |

|||

|

❌ |

✅ |

||

|

On a per-function basis |

✅ |

||

|

❌ |

✅ |

||

|

❌ |

✅ |

Only with |

|

* The CUDA C++ Standard Library functions support queries for small floating-point types, such as numeric_limits<T>, fpclassify(), isfinite(), isnormal(), isinf(), and isnan().

The following sections provide accuracy information for some of these functions, when applicable. It uses ULP for quantification. For more information on the definition of the Unit in the Last Place (ULP), please see Jean-Michel Muller’s paper On the definition of ulp(x).

5.5.6. Built-In Arithmetic Operators#

The built-in C/C++ language operators, such as x + y, x - y, x * y, x / y, x++, x--, and reciprocal 1 / x, for single-, double-, and quad-precision types comply with the IEEE-754 standard. They guarantee a maximum ULP error of zero using a round-to-nearest-even rounding mode. They are available in both host and device code.

The nvcc compilation flag -fmad=true, also included in --use_fast_math, enables contraction of floating-point multiplies and adds/subtracts into floating-point multiply-add operations and has the following effect on the maximum ULP error for the single-precision type float:

x * y + z→ __fmaf_rn(x, y, z): 0 ULP

The nvcc compilation flag -prec-div=false, also included in --use_fast_math, has the following effect on the maximum ULP error for the division operator / for the single-precision type float:

x / y→ __fdividef(x, y): 2 ULP1 / x: 1 ULP

5.5.7. CUDA C++ Mathematical Standard Library Functions#

CUDA provides comprehensive support for C++ Standard Library mathematical functions through the cuda::std:: namespace. The functionalities are part of the <cuda/std/cmath> header.

They are available on both host and device code.

The following sections specify the mapping with the CUDA Math APIs and the error bounds of each function when executed on the device.

The maximum ULP error is defined as the absolute value of the difference between the ULPs returned by the function and a correctly rounded result of the corresponding precision obtained according to the round-to-nearest ties-to-even rounding mode.

The error bounds are derived from extensive, though not exhaustive, testing. Therefore, they are not guaranteed.

5.5.7.1. Basic Operations#

CUDA Math API for basic operations are available in both host and device code, except for __float128.

All the following functions have a maximum ULP error of zero.

|

Meaning |

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

\(|x|\) |

||||||

Remainder of \(\dfrac{x}{y}\), computed as \(x - \mathrm{trunc}\left(\dfrac{x}{y}\right) \cdot y\) |

N/A |

N/A |

||||

Remainder of \(\dfrac{x}{y}\), computed as \(x - \mathrm{rint}\left(\dfrac{x}{y}\right) \cdot y\) |

N/A |

N/A |

||||

Remainder and quotient of \(\dfrac{x}{y}\) |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|||

\(x \cdot y + z\) |

__hfma(x, y, z), device-only |

__hfma(x, y, z), device-only |

||||

\(\max(x, y)\) |

||||||

\(\min(x, y)\) |

||||||

\(\max(x-y, 0)\) |

N/A |

N/A |

||||

NaN value from string representation |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

* Mathematical functions marked with “N/A” are not natively available for CUDA-extended floating-point types, such as __half and __nv_bfloat16. In these cases, the functions are emulated by converting to a float type and then converting the result back.

5.5.7.2. Exponential Functions#

CUDA Math API for exponential functions are available in both host and device code only for float and double types.

|

Meaning |

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

hexp(x) |

hexp(x) |

expf(x) |

exp(x) |

__nv_fp128_exp(x) |

|

|

hexp2(x) |

hexp2(x) |

exp2f(x) |

exp2(x) |

__nv_fp128_exp2(x) |

|

|

|

|

expm1f(x) |

expm1(x) |

__nv_fp128_expm1(x) |

|

|

hlog(x) |

hlog(x) |

logf(x) |

log(x) |

__nv_fp128_log(x) |

|

|

hlog10(x) |

hlog10(x) |

log10f(x) |

log10(x) |

__nv_fp128_log10(x) |

|

|

hlog2(x) |

hlog2(x) |

log2f(x) |

log2(x) |

__nv_fp128_log2(x) |

|

|

|

|

log1pf(x) |

log1p(x) |

__nv_fp128_log1p(x) |

* Mathematical functions marked with “N/A” are not natively available for CUDA-extended floating-point types, such as __half and __nv_bfloat16. In these cases, the functions are emulated by converting to a float type and then converting the result back.

5.5.7.3. Power Functions#

CUDA Math API for power functions are available in both host and device code only for float and double types.

|

Meaning |

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

powf(x, y) |

pow(x, y) |

__nv_fp128_pow(x, y) |

|

|

hsqrt(x) |

hsqrt(x) |

sqrtf(x) |

sqrt(x) |

__nv_fp128_sqrt(x) |

|

|

|

|

cbrtf(x) |

cbrt(x) |

|

|

|

|

|

hypotf(x, y) |

hypot(x, y) |

__nv_fp128_hypot(x, y) |

* Mathematical functions marked with “N/A” are not natively available for CUDA-extended floating-point types, such as __half and __nv_bfloat16. In these cases, the functions are emulated by converting to a float type and then converting the result back.

5.5.7.4. Trigonometric Functions#

CUDA Math API for trigonometric functions are available in both host and device code only for float and double types.

|

Meaning |

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

hsin(x) |

hsin(x) |

sinf(x) |

sin(x) |

__nv_fp128_sin(x) |

|

|

hcos(x) |

hcos(x) |

cosf(x) |

cos(x) |

__nv_fp128_cos(x) |

|

|

|

|

tanf(x) |

tan(x) |

__nv_fp128_tan(x) |

|

|

|

|

asinf(x) |

asin(x) |

__nv_fp128_asin(x) |

|

|

|

|

acosf(x) |

acos(x) |

__nv_fp128_acos(x) |

|

|

|

|

atanf(x) |

atan(x) |

__nv_fp128_atan(x) |

|

|

|

|

atan2f(y, x) |

atan2(y, x) |

|

* Mathematical functions marked with “N/A” are not natively available for CUDA-extended floating-point types, such as __half and __nv_bfloat16. In these cases, the functions are emulated by converting to a float type and then converting the result back.

5.5.7.5. Hyperbolic Functions#

CUDA Math API for hyperbolic functions are available in both host and device code only for float and double types.

|

Meaning |

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

sinhf(x) |

sinh(x) |

__nv_fp128_sinh(x) |

|

|

|

|

coshf(x) |

cosh(x) |

__nv_fp128_cosh(x) |

|

|

htanh(x) |

htanh(x) |

tanhf(x) |

tanh(x) |

__nv_fp128_tanh(x) |

|

|

|

|

asinhf(x) |

asinh(x) |

__nv_fp128_asinh(x) |

|

|

|

|

acoshf(x) |

acosh(x) |

__nv_fp128_acosh(x) |

|

|

|

|

atanhf(x) |

atanh(x) |

__nv_fp128_atanh(x) |

* Mathematical functions marked with “N/A” are not natively available for CUDA-extended floating-point types, such as __half and __nv_bfloat16. In these cases, the functions are emulated by converting to a float type and then converting the result back.

5.5.7.6. Error and Gamma Functions#

CUDA Math API for error and gamma functions are available in both host and device code for float and double types.

Error and Gamma functions are not natively available for CUDA-extended floating-point types, such as __half and __nv_bfloat16. In these cases, the functions are emulated by converting to a float type and then converting the result back.

|

Meaning |

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

erff(x) |

erf(x) |

|

|

erfcf |

erfc |

|

|

tgammaf(x) |

tgamma(x) |

|

|

lgammaf(x) |

lgamma(x) |

5.5.7.7. Nearest Integer Floating-Point Operations#

CUDA Math API for nearest integer floating-point operations are available in both host and device code only for float and double types.

All the following functions have a maximum ULP error of zero.

|

Meaning |

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

\(\lceil x \rceil\) |

||||||

\(\lfloor x \rfloor\) |

||||||

Truncate to integer |

||||||

Round to nearest integer, ties away from zero |

N/A |

N/A |

||||

Round to integer, ties to even |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|||

Round to integer, ties to even |

||||||

Round to nearest integer, ties to even (returns |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|||

Round to nearest integer, ties to even (returns |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|||

Round to nearest integer, ties away from zero (returns |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|||

Round to nearest integer, ties away from zero (returns |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

* Mathematical functions marked with “N/A” are not natively available for CUDA-extended floating-point types, such as __half and __nv_bfloat16. In these cases, the functions are emulated by converting to a float type and then converting the result back.

Performance Considerations

The recommended way to round a single- or double-precision floating-point operand to an integer is to use the functions rintf() and rint(), not roundf() and round(). This is because roundf() and round() map to multiple instructions in device code, whereas rintf() and rint() map to a single instruction. truncf(), trunc(), ceilf(), ceil(), floorf(), and floor() each map to a single instruction as well.

5.5.7.8. Floating-Point Manipulation Functions#

CUDA Math API for floating-point manipulation functions are available in both host and device code, except for __float128.

Floating-point manipulation functions are not natively available for CUDA-extended floating-point types, such as __half and __nv_bfloat16. In these cases, the functions are emulated by converting to a float type and then converting the result back.

All the following functions have a maximum ULP error of zero.

|

Meaning |

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

Extract mantissa and exponent |

||||

\(x \cdot 2^{\mathrm{n}}\) |

||||

Extract integer and fractional parts |

||||

\(x \cdot 2^n\) |

N/A |

|||

\(x \cdot 2^n\) |

N/A |

|||

\(\lfloor \log_2(|x|) \rfloor\) |

||||

\(\lfloor \log_2(|x|) \rfloor\) |

N/A |

|||

Next representable value toward \(y\) |

N/A |

|||

Copy sign of \(y\) to \(x\) |

5.5.7.9. Classification and Comparison#

CUDA Math API for classification and comparison functions are available in both host and device code, except for __float128.

All the following functions have a maximum ULP error of zero.

|

Meaning |

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Classify \(x\) |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Check if \(x\) is finite |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|||

Check if \(x\) is infinite |

N/A |

|||||

Check if \(x\) is NaN |

||||||

Check if \(x\) is normal |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Check if sign bit is set |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|||

Check if \(x > y\) |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|||

Check if \(x \geq y\) |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|||

Check if \(x < y\) |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|||

Check if \(x \leq y\) |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|||

Check if \(x < y\) or \(x > y\) |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|||

Check if \(x\), \(y\), or both are NaN |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

* Mathematical functions marked with “N/A” are not natively available for CUDA-extended floating-point types, such as __half and __nv_bfloat16.

5.5.8. Non-Standard CUDA Mathematical Functions#

CUDA provides mathematical functions that are not part of the C/C++ Standard Library and are instead offered as extensions. For single- and double-precision functions, host and device code availability is defined on a per-function basis.

This section specifies the error bounds of each function when executed on the device.

The maximum ULP error is defined as the absolute value of the difference between the ULPs returned by the function and a correctly rounded result of the corresponding precision obtained according to the round-to-nearest ties-to-even rounding mode.

The error bounds are derived from extensive, though not exhaustive, testing. Therefore, they are not guaranteed.

Meaning |

|

|

|---|---|---|

\(\dfrac{x}{y}\) |

fdividef(x, y), device-only |

|

|

exp10f(x) |

exp10(x) |

|

norm3df(x, y, z), device-only |

norm3d(x, y, z), device-only |

|

norm4df(x, y, z, t), device-only |

norm4d(x, y, z, t), device-only |

|

normf(dim, p), device-only |

norm(dim, p), device-only |

\(\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{x}}\) |

rsqrtf(x) |

rsqrt(x) |

\(\dfrac{1}{\sqrt[3]{x}}\) |

rcbrtf(x) |

rcbrt(x) |

\(\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{x^2 + y^2}}\) |

rhypotf(x, y), device-only |

rhypot(x, y), device-only |

\(\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{x^2 + y^2 + z^2}}\) |

rnorm3df(x, y, z), device-only |

rnorm3d(x, y, z), device-only |

\(\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{x^2 + y^2 + z^2 + t^2}}\) |

rnorm4df(x, y, z, t), device-only |

rnorm4d(x, y, z, t), device-only |

|

rnormf(dim, p), device-only |

rnorm(dim, p), device-only |

|

cospif(x) |

cospi(x) |

|

sinpif(x) |

sinpi(x) |

|

sincospif(x, sptr, cptr) |

sincospi(x, sptr, cptr) |

|

normcdff(x) |

normcdf(x) |

|

normcdfinvf(x) |

normcdfinv(x) |

|

erfcinvf(x) |

erfcinv(x) |

|

erfcxf(x) |

erfcx(x) |

|

erfinvf(x) |

erfinv(x) |

|

cyl_bessel_i0f(x), device-only |

cyl_bessel_i0(x), device-only |

|

cyl_bessel_i1f(x), device-only |

cyl_bessel_i1(x), device-only |

|

j0f(x) |

j0(x) |

|

j1f(x) |

j1(x) |

|

jnf(n, x) |

jn(n, x) |

|

y0f(x) |

y0(x) |

|

y1f(x) |

y1(x) |

|

ynf(n, x) |

yn(n, x) |

Non-standard CUDA Mathematical functions for __half, __nv_bfloat16, and __float128/_Float128 are only available in device code.

Meaning |

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

\(\dfrac{1}{x}\) |

hrcp(x) |

hrcp(x) |

|

|

hexp10(x) |

hexp10(x) |

__nv_fp128_exp10(x) |

\(\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{x}}\) |

hrsqrt(x) |

hrsqrt(x) |

|

|

htanh_approx(x) |

htanh_approx(x) |

|

5.5.9. Intrinsic Functions#

Intrinsic mathematical functions are faster and less accurate versions of their corresponding CUDA C Standard Library Mathematical functions.

They have the same name prefixed with

__, such as__sinf(x).They are only available in device code.

They are faster because they map to fewer native instructions.

The flag

--use_fast_mathautomatically translates the corresponding CUDA Math API functions into intrinsic functions. See the –use_fast_math Effect section for the full list of affected functions.

5.5.9.1. Basic Intrinsic Functions#

A subset of mathematical intrinsic functions allow to specify the rounding mode:

Functions suffixed with

_rnoperate using the round to nearest even rounding mode.Functions suffixed with

_rzoperate using the round towards zero rounding mode.Functions suffixed with

_ruoperate using the round up (toward positive infinity) rounding mode.Functions suffixed with

_rdoperate using the round down (toward negative infinity) rounding mode.

The __fadd_[rn,rz,ru,rd](), __dadd_rn(), __fmul_[rn,rz,ru,rd](), and __dmul_rn() functions map to addition and multiplication operations that the compiler never merges into the FFMA or DFMA instructions. In contrast, additions and multiplications generated from the * and + operators are often combined into FFMA or DFMA.

The following table lists the single-, double-, and quad-precision floating-point intrinsic functions. All of them have a maximum ULP error of 0 and are IEEE-compliant.

Meaning |

|

|

|---|---|---|

\(x + y\) |

||

\(x - y\) |

||

\(x \cdot y\) |

||

\(x \cdot y + z\) |

||

\(\dfrac{x}{y}\) |

||

\(\dfrac{1}{x}\) |

||

\(\sqrt{x}\) |

5.5.9.2. Single-Precision-Only Intrinsic Functions#

The following table lists the single-precision floating-point intrinsic functions with their maximum ULP error.

The maximum ULP error is stated as the absolute value of the difference in ULPs between the result returned by the CUDA library function and a correctly rounded single-precision result obtained according to the round-to-nearest ties-to-even rounding mode.

The error bounds are derived from extensive, though not exhaustive, testing. Therefore, they are not guaranteed.

Function |

Meaning |

Maximum ULP Error |

|---|---|---|

\(\dfrac{x}{y}\) |

\(2\) for \(|y| \in [2^{-126}, 2^{126}]\) |

|

\(e^x\) |

\(2 + \lfloor |1.173 \cdot x| \rfloor\) |

|

\(10^x\) |

\(2 + \lfloor |2.97 \cdot x| \rfloor\) |

|

\(x^y\) |

Derived from |

|

\(\ln(x)\) |

▪ \(2^{-21.41}\) abs error for \(x \in [0.5, 2]\) |

|

\(\log_2(x)\) |

▪ \(2^{-22}\) abs error for \(x \in [0.5, 2]\) |

|

\(\log_{10}(x)\) |

▪ \(2^{-24}\) abs error for \(x \in [0.5, 2]\) |

|

\(\sin(x)\) |

▪ \(2^{-21.41}\) abs error for \(x \in [-\pi, \pi]\) |

|

\(\cos(x)\) |

▪ \(2^{-21.41}\) abs error for \(x \in [-\pi, \pi]\) |

|

\(\sin(x), \cos(x)\) |

Component-wise, the same as |

|

\(\tan(x)\) |

Derived from |

|

\(\tanh(x)\) |

▪ Max relative error: \(2^{-11}\) |

5.5.9.3. --use_fast_math Effect#

The nvcc compiler flag --use_fast_math translates a subset of CUDA Math API functions called in device code into their intrinsic counterpart. Note that the CUDA C++ Standard Library functions are also affected by this flag.

See the Intrinsic Functions section for more details on the implications of using intrinsic functions instead of CUDA Math API functions.

A more robust approach is to selectively replace mathematical function calls with intrinsic versions only where the performance gains justify it and where the changed properties, such as reduced accuracy and different special-case handling, are acceptable.

Device Function |

Intrinsic Function |

|---|---|

5.5.10. References#

Jean-Michel Muller. On the definition of ulp(x). INRIA/LIP research report, 2005.

Nathan Whitehead, Alex Fit-Florea. Precision & Performance: Floating Point and IEEE 754 Compliance for NVIDIA GPUs. Nvidia Report, 2011.

David Goldberg. What every computer scientist should know about floating-point arithmetic. ACM Computing Surveys, March 1991.

David Monniaux. The pitfalls of verifying floating-point computations. ACM Transactions on Programming Languages and Systems, May 2008.

Peter Dinda, Conor Hetland. Do Developers Understand IEEE Floating Point?. IEEE International Parallel and Distributed Processing Symposium (IPDPS), 2018.