3.3. The CUDA Driver API#

Previous sections of this guide have covered the CUDA runtime. As mentioned in CUDA Runtime API and CUDA Driver API, the CUDA runtime is written on top of the lower level CUDA driver API. This section covers some of the differences between the CUDA runtime and the driver APIs, as well has how to intermix them. Most applications can operate at full performance without ever needing to interact with the CUDA driver API. However, new interfaces are sometimes available in the driver API earlier than the runtime API, and some advanced interfaces, such as Virtual Memory Management, are only exposed in the driver API.

The driver API is implemented in the cuda dynamic library (cuda.dll or cuda.so) which is copied on the system during the installation of the device driver. All its entry points are prefixed with cu.

It is a handle-based, imperative API: Most objects are referenced by opaque handles that may be specified to functions to manipulate the objects.

The objects available in the driver API are summarized in Table 6.

Object |

Handle |

Description |

|---|---|---|

Device |

CUdevice |

CUDA-enabled device |

Context |

CUcontext |

Roughly equivalent to a CPU process |

Module |

CUmodule |

Roughly equivalent to a dynamic library |

Function |

CUfunction |

Kernel |

Heap memory |

CUdeviceptr |

Pointer to device memory |

CUDA array |

CUarray |

Opaque container for one-dimensional or two-dimensional data on the device, readable via texture or surface references |

Texture object |

CUtexref |

Object that describes how to interpret texture memory data |

Surface reference |

CUsurfref |

Object that describes how to read or write CUDA arrays |

Stream |

CUstream |

Object that describes a CUDA stream |

Event |

CUevent |

Object that describes a CUDA event |

The driver API must be initialized with cuInit() before any function from the driver API is called. A CUDA context must then be created that is attached to a specific device and made current to the calling host thread as detailed in Context.

Within a CUDA context, kernels are explicitly loaded as PTX or binary objects by the host code as described in Module. Kernels written in C++ must therefore be compiled separately into PTX or binary objects. Kernels are launched using API entry points as described in Kernel Execution.

Any application that wants to run on future device architectures must load PTX, not binary code. This is because binary code is architecture-specific and therefore incompatible with future architectures, whereas PTX code is compiled to binary code at load time by the device driver.

Here is the host code of the sample from Kernels written using the driver API:

int main()

{

int N = ...;

size_t size = N * sizeof(float);

// Allocate input vectors h_A and h_B in host memory

float* h_A = (float*)malloc(size);

float* h_B = (float*)malloc(size);

// Initialize input vectors

...

// Initialize

cuInit(0);

// Get number of devices supporting CUDA

int deviceCount = 0;

cuDeviceGetCount(&deviceCount);

if (deviceCount == 0) {

printf("There is no device supporting CUDA.\n");

exit (0);

}

// Get handle for device 0

CUdevice cuDevice;

cuDeviceGet(&cuDevice, 0);

// Create context

CUcontext cuContext;

cuCtxCreate(&cuContext, 0, cuDevice);

// Create module from binary file

CUmodule cuModule;

cuModuleLoad(&cuModule, "VecAdd.ptx");

// Allocate vectors in device memory

CUdeviceptr d_A;

cuMemAlloc(&d_A, size);

CUdeviceptr d_B;

cuMemAlloc(&d_B, size);

CUdeviceptr d_C;

cuMemAlloc(&d_C, size);

// Copy vectors from host memory to device memory

cuMemcpyHtoD(d_A, h_A, size);

cuMemcpyHtoD(d_B, h_B, size);

// Get function handle from module

CUfunction vecAdd;

cuModuleGetFunction(&vecAdd, cuModule, "VecAdd");

// Invoke kernel

int threadsPerBlock = 256;

int blocksPerGrid =

(N + threadsPerBlock - 1) / threadsPerBlock;

void* args[] = { &d_A, &d_B, &d_C, &N };

cuLaunchKernel(vecAdd,

blocksPerGrid, 1, 1, threadsPerBlock, 1, 1,

0, 0, args, 0);

...

}

Full code can be found in the vectorAddDrv CUDA sample.

3.3.1. Context#

A CUDA context is analogous to a CPU process. All resources and actions performed within the driver API are encapsulated inside a CUDA context, and the system automatically cleans up these resources when the context is destroyed. Besides objects such as modules and texture or surface references, each context has its own distinct address space. As a result, CUdeviceptr values from different contexts reference different memory locations.

A host thread may have only one device context current at a time. When a context is created with cuCtxCreate(), it is made current to the calling host thread. CUDA functions that operate in a context (most functions that do not involve device enumeration or context management) will return CUDA_ERROR_INVALID_CONTEXT if a valid context is not current to the thread.

Each host thread has a stack of current contexts. cuCtxCreate() pushes the new context onto the top of the stack. cuCtxPopCurrent() may be called to detach the context from the host thread. The context is then “floating” and may be pushed as the current context for any host thread. cuCtxPopCurrent() also restores the previous current context, if any.

A usage count is also maintained for each context. cuCtxCreate() creates a context with a usage count of 1. cuCtxAttach() increments the usage count and cuCtxDetach() decrements it. A context is destroyed when the usage count goes to 0 when calling cuCtxDetach() or cuCtxDestroy().

The driver API is interoperable with the runtime and it is possible to access the primary context (see Runtime Initialization) managed by the runtime from the driver API via cuDevicePrimaryCtxRetain().

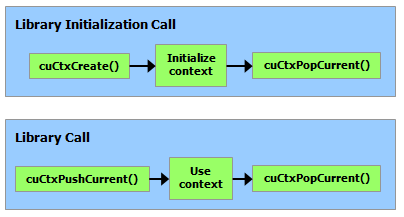

Usage count facilitates interoperability between third party authored code operating in the same context. For example, if three libraries are loaded to use the same context, each library would call cuCtxAttach() to increment the usage count and cuCtxDetach() to decrement the usage count when the library is done using the context. For most libraries, it is expected that the application will have created a context before loading or initializing the library; that way, the application can create the context using its own heuristics, and the library simply operates on the context handed to it. Libraries that wish to create their own contexts - unbeknownst to their API clients who may or may not have created contexts of their own - would use cuCtxPushCurrent() and cuCtxPopCurrent() as illustrated in the following figure.

Figure 20 Library Context Management#

3.3.2. Module#

Modules are dynamically loadable packages of device code and data, akin to DLLs in Windows, that are output by nvcc (see Compilation with NVCC). The names for all symbols, including functions, global variables, and texture or surface references, are maintained at module scope so that modules written by independent third parties may interoperate in the same CUDA context.

This code sample loads a module and retrieves a handle to some kernel:

CUmodule cuModule;

cuModuleLoad(&cuModule, "myModule.ptx");

CUfunction myKernel;

cuModuleGetFunction(&myKernel, cuModule, "MyKernel");

This code sample compiles and loads a new module from PTX code and parses compilation errors:

#define BUFFER_SIZE 8192

CUmodule cuModule;

CUjit_option options[3];

void* values[3];

char* PTXCode = "some PTX code";

char error_log[BUFFER_SIZE];

int err;

options[0] = CU_JIT_ERROR_LOG_BUFFER;

values[0] = (void*)error_log;

options[1] = CU_JIT_ERROR_LOG_BUFFER_SIZE_BYTES;

values[1] = (void*)BUFFER_SIZE;

options[2] = CU_JIT_TARGET_FROM_CUCONTEXT;

values[2] = 0;

err = cuModuleLoadDataEx(&cuModule, PTXCode, 3, options, values);

if (err != CUDA_SUCCESS)

printf("Link error:\n%s\n", error_log);

This code sample compiles, links, and loads a new module from multiple PTX codes and parses link and compilation errors:

#define BUFFER_SIZE 8192

CUmodule cuModule;

CUjit_option options[6];

void* values[6];

float walltime;

char error_log[BUFFER_SIZE], info_log[BUFFER_SIZE];

char* PTXCode0 = "some PTX code";

char* PTXCode1 = "some other PTX code";

CUlinkState linkState;

int err;

void* cubin;

size_t cubinSize;

options[0] = CU_JIT_WALL_TIME;

values[0] = (void*)&walltime;

options[1] = CU_JIT_INFO_LOG_BUFFER;

values[1] = (void*)info_log;

options[2] = CU_JIT_INFO_LOG_BUFFER_SIZE_BYTES;

values[2] = (void*)BUFFER_SIZE;

options[3] = CU_JIT_ERROR_LOG_BUFFER;

values[3] = (void*)error_log;

options[4] = CU_JIT_ERROR_LOG_BUFFER_SIZE_BYTES;

values[4] = (void*)BUFFER_SIZE;

options[5] = CU_JIT_LOG_VERBOSE;

values[5] = (void*)1;

cuLinkCreate(6, options, values, &linkState);

err = cuLinkAddData(linkState, CU_JIT_INPUT_PTX,

(void*)PTXCode0, strlen(PTXCode0) + 1, 0, 0, 0, 0);

if (err != CUDA_SUCCESS)

printf("Link error:\n%s\n", error_log);

err = cuLinkAddData(linkState, CU_JIT_INPUT_PTX,

(void*)PTXCode1, strlen(PTXCode1) + 1, 0, 0, 0, 0);

if (err != CUDA_SUCCESS)

printf("Link error:\n%s\n", error_log);

cuLinkComplete(linkState, &cubin, &cubinSize);

printf("Link completed in %fms. Linker Output:\n%s\n", walltime, info_log);

cuModuleLoadData(cuModule, cubin);

cuLinkDestroy(linkState);

It’s possible to accelerate some parts of the module linking/loading process by using multiple threads, including when loading a cubin. This code sample uses CU_JIT_BINARY_LOADER_THREAD_COUNT to speed up module loading.

#define BUFFER_SIZE 8192

CUmodule cuModule;

CUjit_option options[3];

void* values[3];

char* cubinCode = "some cubin code";

char error_log[BUFFER_SIZE];

int err;

options[0] = CU_JIT_ERROR_LOG_BUFFER;

values[0] = (void*)error_log;

options[1] = CU_JIT_ERROR_LOG_BUFFER_SIZE_BYTES;

values[1] = (void*)BUFFER_SIZE;

options[2] = CU_JIT_BINARY_LOADER_THREAD_COUNT;

values[2] = 0; // Use as many threads as CPUs on the machine

err = cuModuleLoadDataEx(&cuModule, cubinCode, 3, options, values);

if (err != CUDA_SUCCESS)

printf("Link error:\n%s\n", error_log);

Full code can be found in the ptxjit CUDA sample.

3.3.3. Kernel Execution#

cuLaunchKernel() launches a kernel with a given execution configuration.

Parameters are passed either as an array of pointers (next to last parameter of cuLaunchKernel()) where the nth pointer corresponds to the nth parameter and points to a region of memory from which the parameter is copied, or as one of the extra options (last parameter of cuLaunchKernel()).

When parameters are passed as an extra option (the CU_LAUNCH_PARAM_BUFFER_POINTER option), they are passed as a pointer to a single buffer where parameters are assumed to be properly offset with respect to each other by matching the alignment requirement for each parameter type in device code.

Alignment requirements in device code for the built-in vector types are listed in Table 42. For all other basic types, the alignment requirement in device code matches the alignment requirement in host code and can therefore be obtained using __alignof(). The only exception is when the host compiler aligns double and long long (and long on a 64-bit system) on a one-word boundary instead of a two-word boundary (for example, using gcc’s compilation flag -mno-align-double) since in device code these types are always aligned on a two-word boundary.

CUdeviceptr is an integer, but represents a pointer, so its alignment requirement is __alignof(void*).

The following code sample uses a macro (ALIGN_UP()) to adjust the offset of each parameter to meet its alignment requirement and another macro (ADD_TO_PARAM_BUFFER()) to add each parameter to the parameter buffer passed to the CU_LAUNCH_PARAM_BUFFER_POINTER option.

#define ALIGN_UP(offset, alignment) \

(offset) = ((offset) + (alignment) - 1) & ~((alignment) - 1)

char paramBuffer[1024];

size_t paramBufferSize = 0;

#define ADD_TO_PARAM_BUFFER(value, alignment) \

do { \

paramBufferSize = ALIGN_UP(paramBufferSize, alignment); \

memcpy(paramBuffer + paramBufferSize, \

&(value), sizeof(value)); \

paramBufferSize += sizeof(value); \

} while (0)

int i;

ADD_TO_PARAM_BUFFER(i, __alignof(i));

float4 f4;

ADD_TO_PARAM_BUFFER(f4, 16); // float4's alignment is 16

char c;

ADD_TO_PARAM_BUFFER(c, __alignof(c));

float f;

ADD_TO_PARAM_BUFFER(f, __alignof(f));

CUdeviceptr devPtr;

ADD_TO_PARAM_BUFFER(devPtr, __alignof(devPtr));

float2 f2;

ADD_TO_PARAM_BUFFER(f2, 8); // float2's alignment is 8

void* extra[] = {

CU_LAUNCH_PARAM_BUFFER_POINTER, paramBuffer,

CU_LAUNCH_PARAM_BUFFER_SIZE, ¶mBufferSize,

CU_LAUNCH_PARAM_END

};

cuLaunchKernel(cuFunction,

blockWidth, blockHeight, blockDepth,

gridWidth, gridHeight, gridDepth,

0, 0, 0, extra);

The alignment requirement of a structure is equal to the maximum of the alignment requirements of its fields. The alignment requirement of a structure that contains built-in vector types, CUdeviceptr, or non-aligned double and long long, might therefore differ between device code and host code. Such a structure might also be padded differently. The following structure, for example, is not padded at all in host code, but it is padded in device code with 12 bytes after field f since the alignment requirement for field f4 is 16.

typedef struct {

float f;

float4 f4;

} myStruct;

3.3.4. Interoperability between Runtime and Driver APIs#

An application can mix runtime API code with driver API code.

If a context is created and made current via the driver API, subsequent runtime calls will use this context instead of creating a new one.

If the runtime is initialized, cuCtxGetCurrent() can be used to retrieve the context created during initialization. This context can be used by subsequent driver API calls.

The implicitly created context from the runtime is called the primary context (see Runtime Initialization). It can be managed from the driver API with the Primary Context Management functions.

Device memory can be allocated and freed using either API. CUdeviceptr can be cast to regular pointers and vice-versa:

CUdeviceptr devPtr;

float* d_data;

// Allocation using driver API

cuMemAlloc(&devPtr, size);

d_data = (float*)devPtr;

// Allocation using runtime API

cudaMalloc(&d_data, size);

devPtr = (CUdeviceptr)d_data;

In particular, this means that applications written using the driver API can invoke libraries written using the runtime API (such as cuFFT, cuBLAS, …).

All functions from the device and version management sections of the reference manual can be used interchangeably.