2.2. Writing CUDA SIMT Kernels#

CUDA C++ kernels can largely be written in the same way that traditional CPU code would be written for a given problem. However, there are some unique features of the GPU that can be used to improve performance. Additionally, some understanding of how threads on the GPU are scheduled, how they access memory, and how their execution proceeds can help developers write kernels that maximize utilization of the available computing resources.

2.2.1. Basics of SIMT#

From the developer’s perspective, the CUDA thread is the fundamental unit of parallelism. Warps and SIMT describes the basic SIMT model of GPU execution and SIMT Execution Model provides additional details of the SIMT model. The SIMT model allows each thread to maintain its own state and control flow. From a functional perspective, each thread can execute a separate code path. However, substantial performance improvements can be realized by taking care that kernel code minimizes the situations where threads in the same warp take divergent code paths.

2.2.2. Thread Hierarchy#

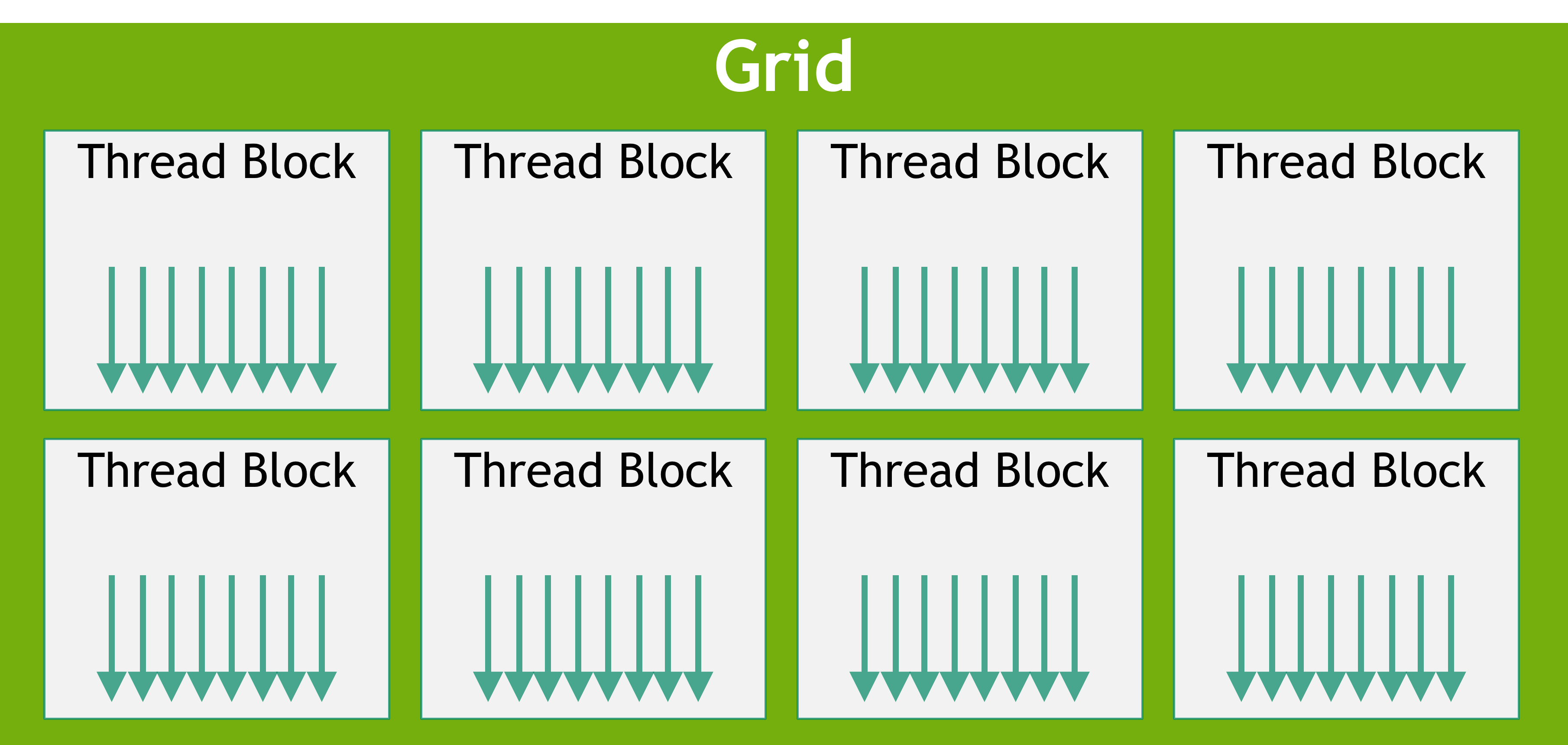

Threads are organized into thread blocks, which are then organized into a grid. Grids may be 1, 2, or 3 dimensional and the size of the grid can be queried inside a kernel with the gridDim built-in variable. Thread blocks may also be 1, 2, or 3 dimensional. The size of the thread block can be queried inside a kernel with the blockDim built-in variable. The index of the thread block can be queried with the blockIdx built-in variable. Within a thread block, the index of the thread is obtained using the threadIdx built-in variable. These built-in variables are used to compute a unique global thread index for each thread, thereby enabling each thread to load/store specific data from global memory and execute a unique code path as needed.

gridDim.[x|y|z]: Size of the grid in thex,yandzdimension respectively. These values are set at kernel launch.blockDim.[x|y|z]: Size of the block in thex,yandzdimension respectively. These values are set at kernel launch.blockIdx.[x|y|z]: Index of the block in thex,yandzdimension respectively. These values change depending on which block is executing.threadIdx.[x|y|z]: Index of the thread in thex,yandzdimension respectively. These values change depending on which thread is executing.

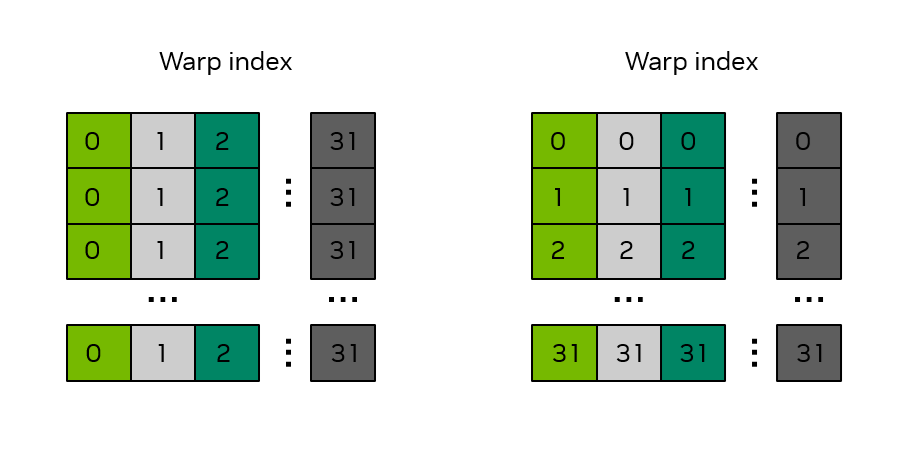

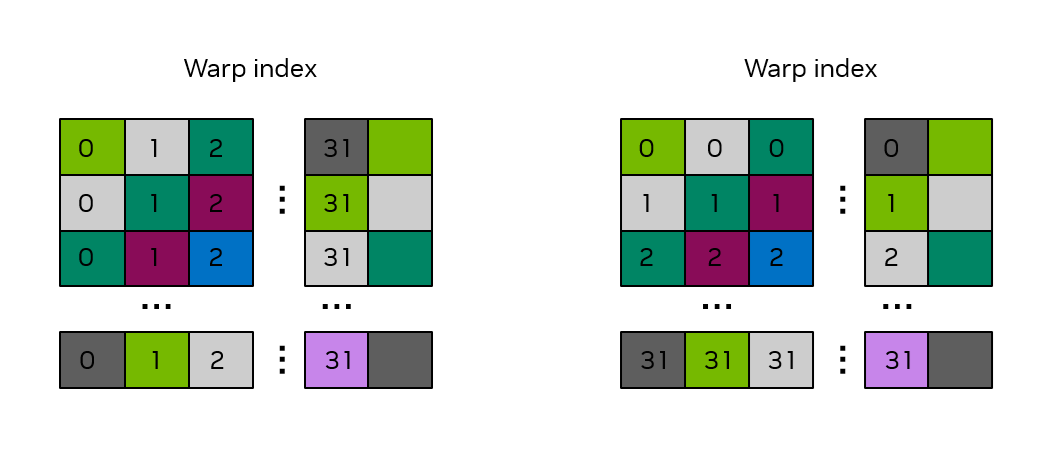

The use of multi-dimensional thread blocks and grids is for convenience only and does not affect performance. The threads of a block are linearized predictably: the first index x moves the fastest, followed by y and then z. This means that in the linearization of a thread indices, consecutive values of threadIdx.x indicate consecutive threads, threadIdx.y has a stride of blockDim.x, and threadIdx.z has a stride of blockDim.x * blockDim.y. This affects how threads are assigned to warps, as detailed in Hardware Multithreading.

Figure 9 shows a simple example of a 2D grid, with 1D thread blocks.

Figure 9 Grid of Thread Blocks#

2.2.3. GPU Device Memory Spaces#

CUDA devices have several memory spaces that can be accessed by CUDA threads within kernels. Table 1 shows a summary of the common memory types, their thread scopes, and their lifetimes. The following sections explain each of these memory types in more detail.

Memory Type |

Scope |

Lifetime |

Location |

|---|---|---|---|

Global |

Grid |

Application |

Device |

Constant |

Grid |

Application |

Device |

Shared |

Block |

Kernel |

SM |

Local |

Thread |

Kernel |

Device |

Register |

Thread |

Kernel |

SM |

2.2.3.1. Global Memory#

Global memory (also called device memory) is the primary memory space for storing data that is accessible by all threads in a kernel. It is similar to RAM in a CPU system. Kernels running on the GPU have direct access to global memory in the same way code running on the CPU has access to system memory.

Global memory is persistent. That is, an allocation made in global memory and the data stored in it persist until the allocation is freed or until the application is terminated. cudaDeviceReset also frees all allocations.

Global memory is allocated with CUDA API calls such as cudaMalloc and cudaMallocManaged. Data can be copied into global memory from CPU memory using CUDA runtime API calls such as cudaMemcpy. Global memory allocations made with CUDA APIs are freed using cudaFree.

Prior to a kernel launch, global memory is allocated and initialized by CUDA API calls. During kernel execution, data from global memory can be read by the CUDA threads, and the result from operations carried out by CUDA threads can be written back to global memory. Once a kernel has completed execution, the results it wrote to global memory can be copied back to the host or used by other kernels on the GPU.

Because global memory is accessible by all threads in a grid, care must be taken to avoid data races between threads. Since CUDA kernels launched from the host have the return type void, the only way for numerical results computed by a kernel to be returned to the host is by writing those results to global memory.

A simple example illustrating the use of global memory is the vecAdd kernel below, where the three arrays A, B, and C are in global memory and are being accessed by this vector add kernel.

__global__ void vecAdd(float* A, float* B, float* C, int vectorLength)

{

int workIndex = threadIdx.x + blockIdx.x*blockDim.x;

if(workIndex < vectorLength)

{

C[workIndex] = A[workIndex] + B[workIndex];

2.2.3.3. Registers#

Registers are located on the SM and have thread local scope. Register usage is managed by the compiler and registers are used for thread local storage during the execution of a kernel. The number of registers per SM and the number of registers per thread block can be queried using the regsPerMultiprocessor and regsPerBlock device properties of the GPU.

NVCC allows the developer to specify a maximum number of registers to be used by a kernel via the -maxrregcount option. Using this option to reduce the number of registers a kernel can use may result in more thread blocks being scheduled on the SM concurrently, but may also result in more register spilling.

2.2.3.4. Local Memory#

Local memory is thread local storage similar to registers and managed by NVCC, but the physical location of local memory is in the global memory space. The ‘local’ label refers to its logical scope, not its physical location. Local memory is used for thread local storage during the execution of a kernel. Automatic variables that the compiler is likely to place in local memory are:

Arrays for which it cannot determine that they are indexed with constant quantities,

Large structures or arrays that would consume too much register space,

Any variable if the kernel uses more registers than available, that is register spilling.

Because the local memory space resides in device memory, local memory accesses have the same latency and bandwidth as global memory accesses and are subject to the same requirements for memory coalescing as described in Coalesced Global Memory Access. Local memory is however organized such that consecutive 32-bit words are accessed by consecutive thread IDs. Accesses are therefore fully coalesced as long as all threads in a warp access the same relative address, such as the same index in an array variable or the same member in a structure variable.

2.2.3.5. Constant Memory#

Constant memory has a grid scope and is accessible for the lifetime of the application. The constant memory resides on the device and is read-only to the kernel. As such, it must be declared and initialized on the host with the __constant__ specifier, outside any function.

The __constant__ memory space specifier declares a variable that:

Resides in constant memory space,

Has the lifetime of the CUDA context in which it is created,

Has a distinct object per device,

Is accessible from all the threads within the grid and from the host through the runtime library (

cudaGetSymbolAddress()/cudaGetSymbolSize()/cudaMemcpyToSymbol()/cudaMemcpyFromSymbol()).

The total amount of constant memory can be queried with the totalConstMem device property element.

Constant memory is useful for small amounts of data that each thread will use in a read-only fashion. Constant memory is small relative to other memories, typically 64KB per device.

An example snippet of declaring and using constant memory follows.

// In your .cu file

__constant__ float coeffs[4];

__global__ void compute(float *out) {

int idx = threadIdx.x;

out[idx] = coeffs[0] * idx + coeffs[1];

}

// In your host code

float h_coeffs[4] = {1.0f, 2.0f, 3.0f, 4.0f};

cudaMemcpyToSymbol(coeffs, h_coeffs, sizeof(h_coeffs));

compute<<<1, 10>>>(device_out);

2.2.3.6. Caches#

GPU devices have a multi-level cache structure which includes L2 and L1 caches.

The L2 cache is located on the device and is shared among all the SMs. The size of the L2 cache can be queried with the l2CacheSize device property element from the function cudaGetDeviceProperties.

As described above in Shared Memory, L1 cache is physically located on each SM and is the same physical space used by shared memory. If no shared memory is utilized by a kernel, the entire physical space will be utilized by the L1 cache.

The L2 and L1 caches can be controlled via functions that allow the developer to specify various caching behaviors. The details of these functions are found in Configuring L1/Shared Memory Balance, L2 Cache Control, and Low-Level Load and Store Functions.

If these hints are not used, the compiler and runtime will do their best to utilize the caches efficiently.

2.2.3.7. Texture and Surface Memory#

Note

Some older CUDA code may use texture memory because, in older NVIDIA GPUs, doing so provided performance benefits in some scenarios. On all currently supported GPUs, these scenarios may be handled using direct load and store instructions, and use of texture and surface memory instructions no longer provides any performance benefit.

A GPU may have specialized instructions for loading data from an image to be used as textures in 3D rendering. CUDA exposes these instructions and the machinery to use them in the texture object API and the surface object API.

Texture and Surface memory are not discussed further in this guide as there is no advantage to using them in CUDA on any currently supported NVIDIA GPU. CUDA developers should feel free to ignore these APIs. For developers working on existing code bases which still use them, explanations of these APIs can still be found in the legacy CUDA C++ Programming Guide.

2.2.4. Memory Performance#

Ensuring proper memory usage is key to achieving high performance in CUDA kernels. This section discusses some general principles and examples for achieving high memory throughput in CUDA kernels.

2.2.4.1. Coalesced Global Memory Access#

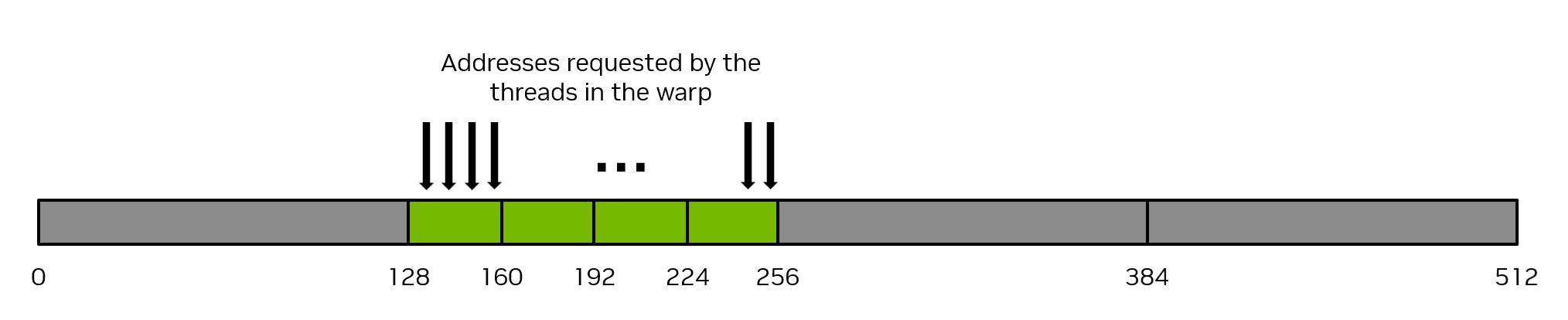

Global memory is accessed via 32-byte memory transactions. When a CUDA thread requests a word of data from global memory, the relevant warp coalesces the memory requests from all the threads in that warp into the number of memory transactions necessary to satisfy the request, depending on the size of the word accessed by each thread and the distribution of the memory addresses across the threads. For example, if a thread requests a 4-byte word, the actual memory transaction the warp will generate to global memory will be 32 bytes in total. To use the memory system most efficiently, the warp should use all the memory that is fetched in a single memory transaction. That is, if a thread is requesting a 4-byte word from global memory, and the transaction size is 32 bytes, if other threads in that warp can use other 4-byte words of data from that 32-byte request, this will result in the most efficient use of the memory system.

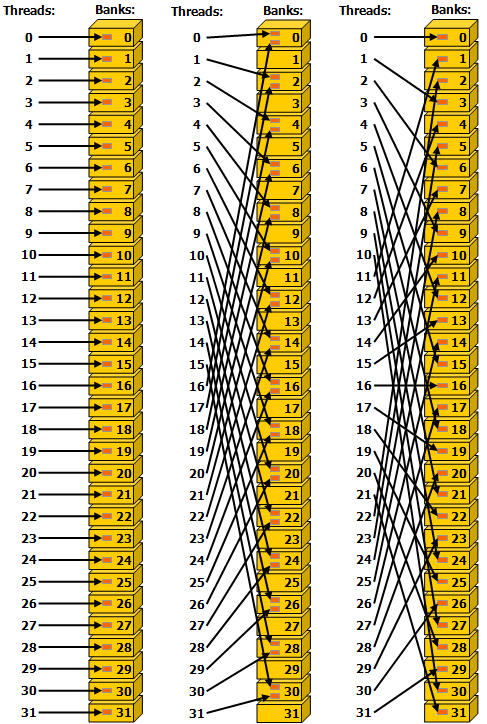

As a simple example, if consecutive threads in the warp request consecutive 4-byte words in memory, then the warp will request 128 bytes of memory total, and this 128 bytes required will be fetched in four 32-byte memory transactions. This results in 100% utilization of the memory system. That is, 100% of the memory traffic is utilized by the warp. Figure 10 illustrates this example of perfectly coalesced memory access.

Figure 10 Coalesced memory access#

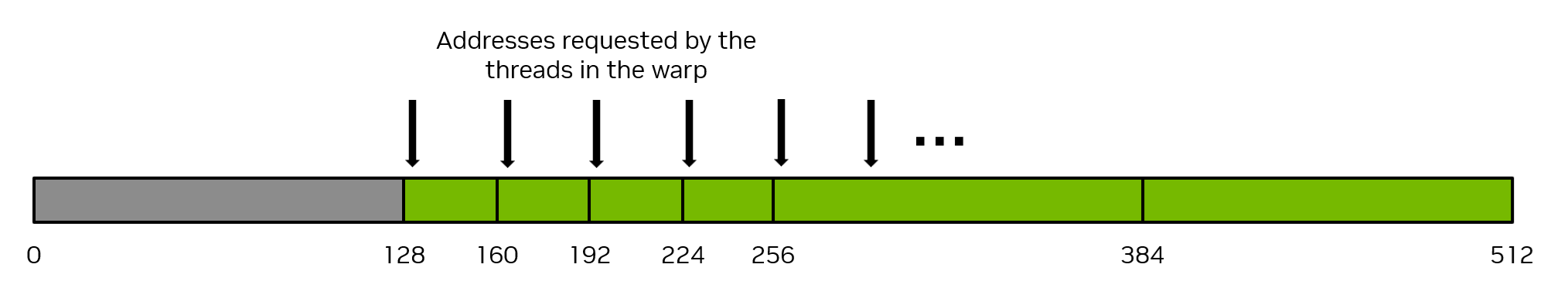

Conversely, the pathologically worst case scenario is when consecutive threads access data elements that are 32 bytes or more apart from each other in memory. In this case, the warp will be forced to issue a 32-byte memory transaction for each thread, and the total number of bytes of memory traffic will be 32 bytes times 32 threads/warp = 1024 bytes. However, the amount of memory used will be 128 bytes only (4 bytes for each thread in the warp), so the memory utilization will only be 128 / 1024 = 12.5%. This is a very inefficient use of the memory system. Figure 11 illustrates this example of uncoalesced memory access.

Figure 11 Uncoalesced memory access#

The most straightforward way to achieve coalesced memory access is for consecutive threads to access consecutive elements in memory. For example, for a kernel launched with 1d thread blocks, the following VecAdd kernel will achieve coalesced memory access. Notice how thread workIndex accesses the three arrays, and consecutive threads (indicated by consecutive values of workIndex) access consecutive elements in the arrays.

__global__ void vecAdd(float* A, float* B, float* C, int vectorLength)

{

int workIndex = threadIdx.x + blockIdx.x*blockDim.x;

if(workIndex < vectorLength)

{

C[workIndex] = A[workIndex] + B[workIndex];

There is no requirement that consecutive threads access consecutive elements of memory to achieve coalesced memory access, it is merely the typical way coalescing is achieved. Coalesced memory access occurs provided all the threads in the warp access elements from the same 32-byte segments of memory in some linear or permuted way. Stated another way, the best way to achieve coalesced memory access is to maximize the ratio of bytes used to bytes transferred.

Note

Ensuring proper coalescing of global memory accesses is one of the most important performance considerations for writing performant CUDA kernels. It is imperative that applications use the memory system as efficiently as possible.

2.2.4.1.1. Matrix Transpose Example Using Global Memory#

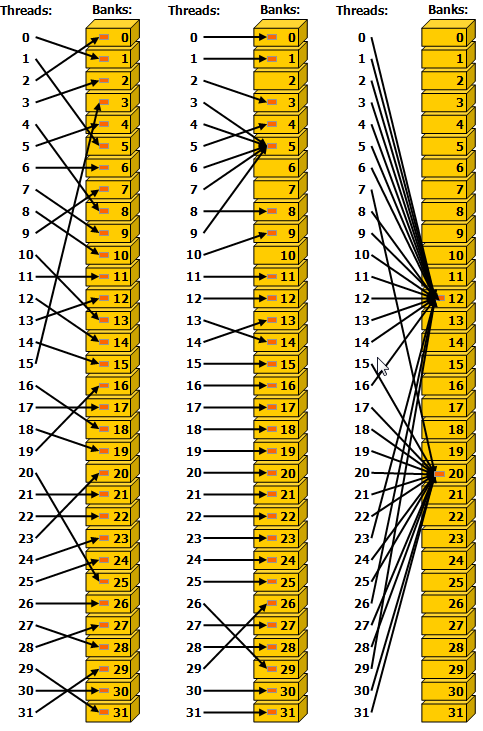

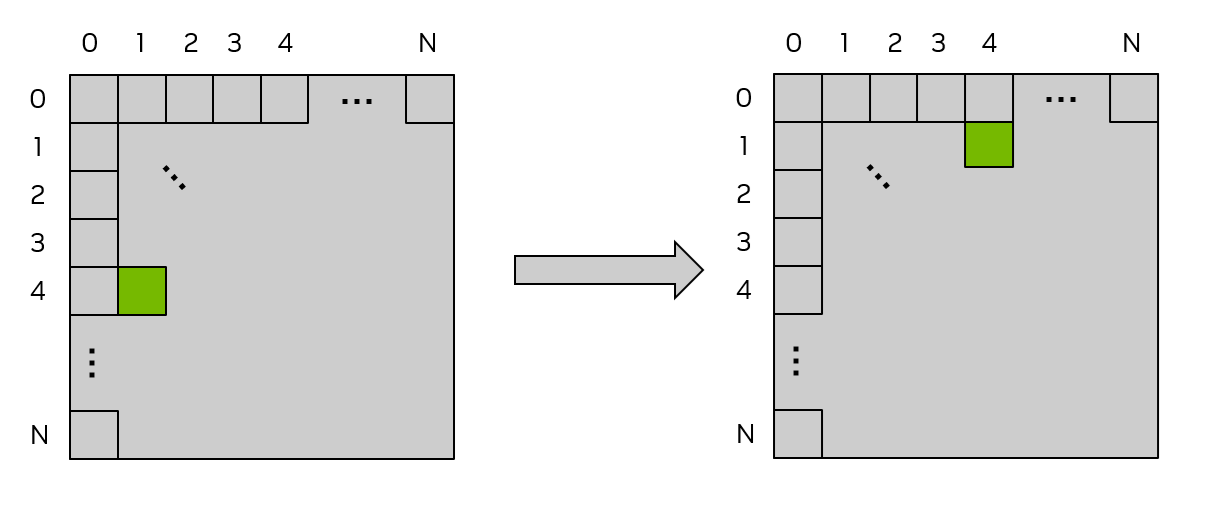

As a simple example, consider an out-of-place matrix transpose kernel that transposes a 32 bit float square matrix of size N x N, from matrix a to matrix c. This example uses a 2d grid, and assumes a launch of 2d thread blocks of size 32 x 32 threads, that is, blockDim.x = 32 and blockDim.y = 32, so each 2d thread block will operate on a 32 x 32 tile of the matrix. Each thread operates on a unique element of the matrix, so no explicit synchronization of threads is necessary. Figure 12 illustrates this matrix transpose operation. The kernel source code follows the figure.

Figure 12 Matrix Transpose using Global memory#

The labels on the top and left of each matrix are the 2d thread block indices and also can be considered the tile indices, where each small square indicates a tile of the matrix that will be operated on by a 2d thread block. In this example, the tile size is 32 x 32 elements, so each of the small squares represents a 32 x 32 tile of the matrix. The green shaded square shows the location of an example tile before and after the transpose operation.

/* macro to index a 1D memory array with 2D indices in row-major order */

/* ld is the leading dimension, i.e. the number of columns in the matrix */

#define INDX( row, col, ld ) ( ( (row) * (ld) ) + (col) )

/* CUDA kernel for naive matrix transpose */

__global__ void naive_cuda_transpose(int m, float *a, float *c )

{

int myCol = blockDim.x * blockIdx.x + threadIdx.x;

int myRow = blockDim.y * blockIdx.y + threadIdx.y;

if( myRow < m && myCol < m )

{

c[INDX( myCol, myRow, m )] = a[INDX( myRow, myCol, m )];

} /* end if */

return;

} /* end naive_cuda_transpose */

To determine whether this kernel is achieving coalesced memory access one needs to determine whether consecutive threads are accessing consecutive elements of memory. In a 2d thread block, the x index moves the fastest, so consecutive values of threadIdx.x should be accessing consecutive elements of memory. threadIdx.x appears in myCol, and one can observe that when myCol is the second argument to the INDX macro, consecutive threads are reading consecutive values of a, so the read of a is perfectly coalesced.

However, the writing of c is not coalesced, because consecutive values of threadIdx.x (again examine myCol) are writing elements to c that are ld (leading dimension) elements apart from each other. This is observed because now myCol is the first argument to the INDX macro, and as the first argument to INDX increments by 1, the memory location changes by ld. When ld is larger than 32 (which occurs whenever the matrix sizes are larger than 32), this is equivalent to the pathological case shown in Figure 11.

To alleviate these uncoalesced writes, the use of shared memory can be employed, which will be described in the next section.

2.2.5. Atomics#

Performant CUDA kernels rely on expressing as much algorithmic parallelism as possible. The asynchronous nature of GPU kernel execution requires that threads operate as independently as possible. It’s not always possible to have complete independence of threads and as we saw in Shared Memory, there exists a mechanism for threads in the same thread block to exchange data and synchronize.

On the level of an entire grid there is no such mechanism to synchronize all threads in a grid. There is however a mechanism to provide synchronous access to global memory locations via the use of atomic functions. Atomic functions allow a thread to obtain a lock on a global memory location and perform a read-modify-write operation on that location. No other thread can access the same location while the lock is held. CUDA provides atomics with the same behavior as the C++ standard library atomics as cuda::std::atomic and cuda::std::atomic_ref. CUDA also provides extended C++ atomics cuda::atomic and cuda::atomic_ref which allow the user to specify the thread scope of the atomic operation. The details of atomic functions are covered in Atomic Functions.

An example usage of cuda::atomic_ref to perform a device-wide atomic addition is as follows, where array is an array of floats, and result is a float pointer to a location in global memory which is the location where the sum of the array will be stored.

__global__ void sumReduction(int n, float *array, float *result) {

...

tid = threadIdx.x + blockIdx.x * blockDim.x;

cuda::atomic_ref<float, cuda::thread_scope_device> result_ref(result);

result_ref.fetch_add(array[tid]);

...

}

Atomic functions should be used sparingly as they enforce thread synchronization that can impact performance.

2.2.6. Cooperative Groups#

Cooperative groups is a software tool available in CUDA C++ that allows applications to define groups of threads which can synchronize with each other, even if that group of threads spans multiple thread blocks, multiple grids on a single GPU, or even across multiple GPUs. The CUDA programming model in general allows threads within a thread block or thread block cluster to synchronize efficiently, but does not provide a mechanism for specifying thread groups smaller than a thread block or cluster. Similarly, the CUDA programming model does not provide mechanisms or guarantees that enable synchronization across thread blocks.

Cooperative groups provide both of these capabilities through software. Cooperative groups allows the application to create thread groups that cross the boundary of thread blocks and clusters, though doing so comes with some semantic limitations and performance implications which are described in detail in the feature section covering cooperative groups.

2.2.7. Kernel Launch and Occupancy#

When a CUDA kernel is launched, CUDA threads are grouped into thread blocks and a grid based on the execution configuration specified at kernel launch. Once the kernel is launched, the scheduler assigns thread blocks to SMs. The details of which thread blocks are scheduled to execute on which SMs cannot be controlled or queried by the application and no ordering guarantees are made by the scheduler, so programs cannot not rely on a specific scheduling order or scheme for correct execution.

The number of blocks that can be scheduled on an SM depends on the hardware resources a given thread block requires, and the hardware resources available on the SM. When a kernel is first launched, the scheduler begins assigning thread blocks to SMs. As long as SMs have sufficient hardware resources unoccupied by other thread blocks, the scheduler will continue assigning thread blocks to SMs. If at some point no SM has the capacity to accept another thread block, the scheduler will wait until the SMs complete previously assigned thread blocks. Once this happens, SMs are free to accept more work, and the scheduler assigns thread blocks to them. This process continues until all thread blocks have been scheduled and executed.

The cudaGetDeviceProperties function allows an application to query the limits of each SM via device properties. Note that there are limits per SM and per thread block.

maxBlocksPerMultiProcessor: The maximum number of resident blocks per SM.sharedMemPerMultiprocessor: The amount of shared memory available per SM in bytes.regsPerMultiprocessor: The number of 32-bit registers available per SM.maxThreadsPerMultiProcessor: The maximum number of resident threads per SM.sharedMemPerBlock: The maximum amount of shared memory that can be allocated by a thread block in bytes.regsPerBlock: The maximum number of 32-bit registers that can be allocated by a thread block.maxThreadsPerBlock: The maximum number of threads per thread block.

The occupancy of a CUDA kernel is the ratio of the number of active warps to the maximum number of active warps supported by the SM. In general, it’s a good practice to have occupancy as high as possible which hides latency and increases performance.

To calculate occupancy, one needs to know the resource limits of the SM, which were just described, and one needs to know what resources are required by the CUDA kernel in question. To determine resource usage on a per kernel basis, during program compilation one can use the --resource-usage option to nvcc, which will show the number of registers and shared memory required by the kernel.

To illustrate, consider a device such as compute capability 10.0 with the device properties enumerated in Table 2.

Resource |

Value |

|---|---|

|

32 |

|

233472 |

|

65536 |

|

2048 |

|

49152 |

|

65536 |

|

1024 |

If a kernel was launched as testKernel<<<512, 768>>>(), i.e., 768 threads per block, each SM would only be able to execute 2 thread blocks at a time. The scheduler cannot assign more than 2 thread blocks per SM because the maxThreadsPerMultiProcessor is 2048. So the occupancy would be (768 * 2) / 2048, or 75%.

If a kernel was launched as testKernel<<<512, 32>>>(), i.e., 32 threads per block, each SM would not run into a limit on maxThreadsPerMultiProcessor, but since the maxBlocksPerMultiProcessor is 32, the scheduler would only be able to assign 32 thread blocks to each SM. Since the number of threads in the block is 32, the total number of threads resident on the SM would be 32 blocks * 32 threads per block, or 1024 total threads. Since a compute capability 10.0 SM has a maximum value of 2048 resident threads per SM, the occupancy in this case is 1024 / 2048, or 50%.

The same analysis can be done with shared memory. If a kernel uses 100KB of shared memory, for example, the scheduler would only be able to assign 2 thread blocks to each SM, because the third thread block on that SM would require another 100KB of shared memory for a total of 300KB, which is more than the 233472 bytes available per SM.

Threads per block and shared memory usage per block are explicitly controlled by the programmer and can be adjusted to achieve the desired occupancy. The programmer has limited control over register usage as the compiler and runtime will attempt to optimize register usage. However the programmer can specify a maximum number of registers per thread block via the --maxrregcount option to nvcc. If the kernel needs more registers than this specified amount, the kernel is likely to spill to local memory, which will change the performance characteristics of the kernel. In some cases even though spilling occurs, limiting registers allows more thread blocks to be scheduled which in turn increases occupancy and may result in a net increase in performance.