Architectures In Modulus

In this section, we discuss some of the advanced and state-of-the-art Deep learning architectures and schemes that have become a part of Modulus library.

Neural networks are generally biased toward low-frequency solutions, a phenomenon that is known as “spectral bias” 1. This can adversely affect the training convergence as well as the accuracy of the model. One approach to alleviate this issue is to perform input encoding, that is, to transform the inputs to a higher dimensional feature space via high-frequency functions 2, 1, 3. This is done in Modulus using the Fourier networks, which takes the following form:

(28)\[ u_{net}(\mathbf{x};\mathbf{\theta}) = \mathbf{W}_n \big \{\phi_{n-1} \circ \phi_{n-2} \circ \cdots \circ \phi_1 \circ \phi_E \big \} (\mathbf{x}) + \mathbf{b}_n, \; \; \; \; \phi_{i}(\mathbf{x}_i) = \sigma \left( \mathbf{W}_i \mathbf{x}_i + \mathbf{b}_i \night),\]

where \(u_{net}(\mathbf{x};\mathbf{\theta})\) is the approximate solution, \(\mathbf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_0}\) is the input to network, \(\phi_{i} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_i}\) is the \(i^{th}\) layer of the network, \(\mathbf{W}_i \in \mathbb{R}^{d_i \times d_{i-1}}, \mathbf{b}_i \in \mathbb{R}^{d_i}\) are the weight and bias of the \(i^{th}\) layer, \(\mathbf{\theta}\) denotes the set of network’s trainable parameters, i.e., \(\mathbf{\theta} = \{\mathbf{W}_1, \mathbf{b}_1, \cdots, \mathbf{b}_n, \mathbf{W}_n\}\), \(n\) is the number of layers, and \(\sigma\) is the activation function. \(\phi_E\) is an input encoding layer, and by setting that to identity function, we arrive at the standard feed-forward fully-connected architecture. The input encoding layer in Modulus is a variation of the one proposed in 3 with trainable encoding, and takes the following form

(29)\[\phi_E = \big[ \sin \left( 2\pi \mathbf{f} \times \mathbf{x} \night); \cos \left( 2\pi \mathbf{f} \times

\mathbf{x} \night) \big]^T,\]

where \(\mathbf{f} \in \mathbb{R}^{n_f \times d_0}\) is the trainable frequency matrix and \(n_f\) is the number of frequency sets.

In the case of parameterized examples, it is also possible to apply encoding to the parameters in addition to the spatial inputs. In fact, it has been observed that applying encoding to the parametric inputs in addition to the spatial inputs will improve the accuracy and the training convergence of the model. Note that Modulus applies the input encoding to the spatial and parametric inputs in a fully decoupled setting and then concatenates the spatial/temporal and parametric Fourier features together. Details on the usage of Fourier net can be found Modulus Configuration while its application for FPGA heat sink can be found in tutorial FPGA Heat Sink with Laminar Flow.

In Fourier network, a standard fully-connected neural network is used as the nonlinear mapping between the Fourier features and the model output. In modified Fourier networks, we use a variant of the fully-connected network similar to the one proposed in 4. Two transformation layers are introduced to project the Fourier features to another learned feature space, and are then used to update the hidden layers through element-wise multiplications, similar to its standard fully connected counterpart in 4. It is shown in tutorial FPGA Heat Sink with Laminar Flow that this multiplicative interaction can improve the training convergence and accuracy, although at the cost of slightly increasing the training time per iteration. The hidden layers in this architecture take the following form

(30)\[\phi_{i}(\mathbf{x}_i) = \left(1 - \sigma \left( \mathbf{W}_i \mathbf{x}_i + \mathbf{b}_i \night) \night) \odot \sigma \left( \mathbf{W}_{T_1} \phi_E + \mathbf{b}_{T_1} \night) + \sigma \left( \mathbf{W}_i \mathbf{x}_i + \mathbf{b}_i \night) \odot \sigma \left( \mathbf{W}_{T_2} \phi_E + \mathbf{b}_{T_2} \night),\]

where \(i>1\) and \(\{ \mathbf{W}_{T_1}, \mathbf{b}_{T_1}\}, \{ \mathbf{W}_{T_2}, \mathbf{b}_{T_2}\}\) are the parameters for the two transformation layers, and \(\phi_E\) takes the form in equation (29). Details on how to use the modified Fourier networks can be found in Modulus Configuration while its application for the FPGA heat sink can be found in tutorial FPGA Heat Sink with Laminar Flow.

Highway Fourier network is a Modulus variation of the Fourier network, inspired by the highway networks proposed in 5. Highway networks consist of adaptive gating units that control the flow of information, and are originally developed to be used in the training of very deep networks 5. The hidden layers in this network take the following form

(31)\[\phi_{i}(\mathbf{x}_i) = \sigma \left( \mathbf{W}_i \mathbf{x}_i + \mathbf{b}_i \night) \odot \sigma_s \left( \mathbf{W}_{T} \phi_E + \mathbf{b}_{T} \night) + \left( \mathbf{W}_P \mathbf{x} + \mathbf{b}_P \night) \odot \left (1 - \sigma_s \left( \mathbf{W}_{T} \phi_E + \mathbf{b}_{T} \night) \night).\]

Here, \(\sigma_s\) is the sigmoid activation, \(\{ \mathbf{W}_{T}, \mathbf{b}_{T}\}\) are the parameters of the transformer layer, and \(\{ \mathbf{W}_{P}, \mathbf{b}_{P}\}\) are the parameters of the projector layer, which basically projects the network inputs to another space to match with the dimensionality of hidden layers. The transformer layer here controls the relative contribution of the network’s hidden state and the network’s input to the output of the hidden layer. It also offers a multiplicative interaction mechanism between the network’s input and hidden states, similar to the modified Fourier network. Details on how to use the highway Fourier networks can be found in Modulus Configuration while its application for the FPGA heat sink can be found in tutorial FPGA Heat Sink with Laminar Flow.

In 9, Wang et. al. proposed a multi-scale Fourier feature network architecture that aim to tackle partial differential equations exhibiting multi-scale behaviors. The key of the proposed architectures is to apply multiple Fourier feature embeddings initialized with different frequencies to input coordinates before passing these embedded inputs through the same fully-connected neural network and finally concatenate the outputs with a linear layer. The forward pass of the multi-scale Fourier feature networks is given by

(32)\[\begin{split}\begin{aligned}

&\phi_{E}^{(i)}(\mathbf{x})=[\sin (2 \pi \mathbf{f}^{(i)} \times \mathbf{x}) ; \cos (2 \pi \mathbf{f}^{(i)} \times \mathbf{x})]^{T}, \quad \text{ for } i=1, 2, \dots, M\\

&\mathbf{H}^{(i)}_1 = \sigma(\mathbf{W}_1 \cdot\phi_{E}^{(i)}(\mathbf{x}) + \mathbf{b}_1), \quad \text{ for } i=1, 2, \dots, M \\

& \mathbf{H}^{(i)}_\ell = \sigma(\mathbf{W}_\ell \cdot \mathbf{H}^{(i)}_{\ell - 1} + \mathbf{b}_\ell), \quad \text{ for } \ell=2, \dots, L, i=1, 2, \dots, M\\

& \mathbf{u}_{net}(\mathbf{x}, {\mathbf{\theta}}) = \mathbf{W}_{L+1} \cdot \left[ \mathbf{H}^{(1)}_L, \mathbf{H}^{(2)}_L, \dots, \mathbf{H}^{(M)}_L \night] + \mathbf{b}_{L+1},\end{aligned}\end{split}\]

where \(\phi_{E}^{(i)}\) and \(\sigma\) denote Fourier feature mappings and activation functions, respectively, and each entry in \(\mathbf{f}^{(i)} \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times d}\) is sampled from a Gaussian distribution \(\mathcal{N}(0, \sigma_i)\). Notice that the weights and the biases of this architecture are essentially the same as in a standard fully-connected neural network with the addition of the trainable Fourier features. Here, we underline that the choice of \(\sigma_i\) is problem dependent and typical values can be \(1, 10, 100,\) etc.

For time-dependent problems, multi-scale behavior may exist not only across spatial directions but also across time. The authors 9 proposed another novel multi-scale Fourier feature architecture to tackle multi-scale problems in spatio-temporal domains. Specifically, the feed-forward pass of the network is now defined as

(33)\[\begin{split}\begin{aligned}

&\phi_{E}^{(x_i)}(x_i)=[\sin (2 \pi \mathbf{f}^{(x_i)} \times x_i) ; \cos (2 \pi \mathbf{f}^{(x_i)} \times \mathbf{x}_i)]^{T}, \\

& \phi_{E}^{(t)}(t)=[\sin (2 \pi \mathbf{f}^{(t)} \times t) ; \cos (2 \pi \mathbf{f}^{(t)} \times x_i)]^{T}, \\

& \mathbf{H}^{(x_i)}_1 = \sigma(\mathbf{W}_1 \cdot \phi_{E}^{(x_i)}(x_i) + \mathbf{b}_1),

\quad \text{ for } i=1, 2, \dots, d,\\

& \mathbf{H}^{(t)}_1 = \sigma(\mathbf{W}_1 \cdot \phi_{E}^{(t)}(t) + \mathbf{b}_1),\\

& \mathbf{H}_{\ell}^{(x_i)} = \sigma(\mathbf{W}_\ell \cdot \mathbf{H}^{(x_i)}_{\ell-1} + \mathbf{b}_\ell), \quad \text{ for } \ell=2, \dots, L \text{ and } i=1,2, \dots, d,\\

& \mathbf{H}^{(t)}_{\ell} = \sigma(\mathbf{W}_\ell \cdot \mathbf{H}^{(t)}_{\ell-1} + \mathbf{b}_\ell), \quad \text{ for } \ell=2, \dots, L, \\

& \mathbf{H}_{L} = \prod_{i=1}^d H^{(x_i)}_{L} \cdot H^{(t)}_{L} , \\

& \mathbf{u}_{net}(\mathbf{x}, t; {\mathbf{\theta}}) = \mathbf{W}_{L+1} \cdot \mathbf{H}_{L} + \mathbf{b}_{L+1},\end{aligned}\end{split}\]

where \(\phi_{E}^{(x_i)}\) and \(\phi_{E}^{(t)}\) denote spatial and temporal Fourier feature mappings, respectively, and \(\odot\) represents the point-wise multiplication. Here, each entry of \(\mathbf{f}^{(x_i)}\) and \(\mathbf{f}^{(t)}\) can be sampled from different Gaussian distributions. One key difference from the multi-scale Fourier feature network is that separate Fourier feature embeddings are applied to spatial and temporal input coordinates before passing the embedded inputs through the same fully-connected network. Another key difference is that network outputs are merged using point-wise multiplication and passing them through a linear layer.

In 6, the authors propose a neural network using Sin activation functions dubbed sinusoidal representation networks or SiReNs. This network has similarities to the Fourier networks above because using a Sin activation function has the same effect as the input encoding for the first layer of the network. A key component of this network architecture is the initialization scheme. The weight matrices of the network are drawn from a uniform distribution \(W \sim U(-\sqrt{\frac{6}{fan\_in}},\sqrt{\frac{6}{fan\_in}})\) where \(fan\_in is\) is the input size to that layer. The input of each Sin activation has a Gauss normal distribution and the output of each Sin activation, an arcSin distribution. This preserves the distribution of activations allowing deep architectures to be constructed and trained effectively 6. The first layer of the network is scaled by a factor \(\omega\) to span multiple periods of the Sin function. This was empirically shown to give good performance and is in line with the benefits of the input encoding in the Fourier network. The authors suggest \(\omega=30\) to perform well under many circumstances and is the default value given in Modulus as well. Details on how to use the SiReN architecture in Modulus can be found in Modulus Configuration.

The DGM architecture is proposed by 7, and consists of several fully-connected layers each of which includes a number of sublayers, similar in spirit to the LSTM architecture, as follows:

(34)\[\begin{split}\begin{split}

&S^1 = \sigma(XW^1 + b^1),\\

&Z^\ell = \sigma(XV_z^{\ell} + S^{\ell}W_z^{\ell} + b_z^{\ell}), \>\>\>\> \forall \ell \in \{1,\cdots,n_{\ell}\},\\

&G^\ell = \sigma(XV_g^{\ell} + S^{\ell}W_g^{\ell} + b_g^{\ell}), \>\>\>\> \forall \ell \in \{1,\cdots,n_{\ell}\},\\

&R^\ell = \sigma(XV_r^{\ell} + S^{\ell}W_r^{\ell} + b_r^{\ell}), \>\>\>\> \forall \ell \in \{1,\cdots,n_{\ell}\},\\

&H^\ell = \sigma(XV_h^{\ell} + (S^\ell \odot R^\ell)^{\ell}W_h^{\ell} + b_h^{\ell}), \>\>\>\> \forall \ell \in \{1,\cdots,n_{\ell}\},\\

&S^{\ell+1} = (1-G^\ell) \odot H^\ell + Z^\ell \odot S^\ell,\\

&u_{net}(X;\theta) = S^{n_\ell+1}W + b.

\end{split}\end{split}\]

The set of DGM network parameters include

(35)\[\theta = \{W^1,b^1,\left(V_z^{\ell},W_z^{\ell},b_z^{\ell}\night)_{\ell=1}^{n_\ell}, \left(V_g^{\ell},W_g^{\ell},b_g^{\ell}\night)_{\ell=1}^{n_\ell}, \left(V_r^{\ell},W_r^{\ell},b_r^{\ell}\night)_{\ell=1}^{n_\ell}, \left(V_h^{\ell},W_h^{\ell},b_h^{\ell}\night)_{\ell=1}^{n_\ell},W,b\}.\]

where \(X\) is the input to the network, \(\sigma(\cdot)\) is the activation function, \(n_\ell\) is the number of hidden layers, \(\odot\) is the Hadamard product, and \(u_{net}(X;\theta)\) is the network output. One important feature of this architecture is that it consists of multiple element-wise multiplication of nonlinear transformations of the input, and that can potentially help with learning complicated functions 7. Application for this architecture using the FPGA heat sink can be found in tutorial FPGA Heat Sink with Laminar Flow.

Multiplicative filter networks 8 consist of linear or nonlinear transformations of Fourier or Gabor filters of the input, multiplied together at each hidden layer, as follows:

(36)\[\begin{split}\begin{split}

&\mathbf{\phi}_1 = f(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{\xi}_1),\\

&\mathbf{\phi}_{i+1} = \sigma \left( \mathbf{W}_i \mathbf{\phi}_i + \mathbf{b}_i \night) \odot f(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{\xi}_{i+1}), \>\>\>\> \forall i \in \{1,\cdots,n-1\},\\

&u_{net}(\mathbf{x};\mathbf{\theta}) = \mathbf{W}_n \mathbf{\phi}_n + \mathbf{b}_n.

\end{split}\end{split}\]

Here, \(f(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{\xi}_{i})\) is a multiplicative Fourier or Gabor filter. The set of multiplicative filter network parameters are \(\theta = \{\mathbf{W}_1, \mathbf{b}_1, \mathbf{\xi}_1, \cdots \mathbf{W}_n, \mathbf{b}_n, \mathbf{\xi}_n \}\). Note that in the original implementation in 8, no activation function is used, and network nonlinearity comes from the multiplicative filters only. In this setting, it has been shown in 8 that the output of a multiplicative Filter network can be represented as a linear combination of Fourier or Gabor bases. In Modulus, the user can choose whether to use activation functions or not. The Fourier filters take the following form:

(37)\[f(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{\xi}_{i}) = \sin(\mathbf{\omega}_i \mathbf{x} + \mathbf{\phi}_i),\]

where \(\mathbf{\xi}_i = \{\mathbf{\omega}_i, \mathbf{\phi}_i\}\). The Gabor filters also take the following form:

(38)\[f(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{\xi}_{i}) = \exp \left( - \frac{\mathbf{\gamma}_i}{2} ||\mathbf{x}-\mathbf{\mu}_i||_2^2 \night) \sin(\mathbf{\omega}_i \mathbf{x} + \mathbf{\phi}_i),\]

where \(\mathbf{\xi}_i = \{\mathbf{\gamma}_i, \mathbf{\mu}_i, \mathbf{\omega}_i, \mathbf{\phi}_i\}\). For details on the multiplicative filter networks and network initialization, please refer to . Details on how to use the multiplicative filter networks can be found in Modulus Configuration.

Fourier neural operator (FNO) is a data-driven architecture which can be used to parameterize solutions for a distribution of PDE solutions 10. The key feature of FNO is the spectral convolutions: operations that place the integral kernel in Fourier space. The spectral convolution (Fourier integral operator) is defined as follows:

(39)\[ (\mathcal{K}(\mathbf{w})\phi)(x) = \mathcal{F}^{-1}(R_{\mathbf{W}}\cdot \left(\mathcal{F}\night)\phi)(x), \quad \forall x \in D\]

where \(\mathcal{F}\) and \(\mathcal{F}^{-1}\) are the forward and inverse Fourier transforms, respectively. \(R_{\mathbf{w}}\) is the transformation which contains the learnable parameters \(\mathbf{w}\). Note this operator is calculated over the entire structured Euclidean domain \(D\) discretized with \(n\) points. Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) is used to perform the Fourier transforms efficiently and the resulting transformation \(R_{\mathbf{w}}\) is just finite size matrix of learnable weights. In side the spectral convolution, the Fourier coefficients are truncated to only the lower modes which intern allows explicit control over the dimensionality of the spectral space and linear operator.

The FNO model is a the composition of a fully-connected “lifting” layer, \(L\) spectral convolutions with point-wise linear skip connections and a decoding point-wise fully-connected neural network at the end.

(40)\[ u_{net}(\Phi;\theta) = \mathcal{Q}\circ \sigma(W_{L} + \mathcal{K}_{L}) \circ ... \circ \sigma(W_{1} + \mathcal{K}_{1})\circ \mathcal{P}(\Phi), \quad \Phi=\left\{\phi(x); \forall x \in D\night\}\]

in which \(\sigma(W_{i} + \mathcal{K}_{i})\) is the spectral convolution layer \(i\) with the point-wise linear transform \(W_{i}\) and activation function \(\sigma(\cdot)\). \(\mathcal{P}\) is the point-wise lifting network that projects the input into a higher dimensional latent space, \(\mathcal{P}: \mathbb{R}^{d_in} \nightarrow \mathbb{R}^{k}\). Similarly \(\mathcal{Q}\) is the point-wise fully-connected decoding network, \(\mathcal{P}: \mathbb{R}^{k} \nightarrow \mathbb{R}^{d_out}\). Since all fully-connected components of FNO are point-wise operations, the model is invariant to the dimensionality of the input. Additional information on FNO and its implementation in Modulus can be found in the example Darcy Flow with Fourier Neural Operator.

While FNO is technically invariant to the dimensionality of the discretized domain \(D\), this domain must be a structured grid in Euclidean space. The inputs to FNO are analogous to images, but the model is invariant to the image resolution.

The Adaptive Fourier Neural Operator (AFNO) 11 architecture is highly effective and computationally efficient for high-resolution inputs. It combines a key recent advance in modeling PDE systems, namely the Fourier Neural Operator (FNO) with the powerful Vision Transformer (ViT) model for image processing. FNO has shown great results in modeling PDE systems such as Navier-Stokes flows. The ViT and related variants of transformer models have achieved SOTA performance in image processing tasks. The multi-head self-attention (MHSA) mechanism of the ViT is key to its impressive performance. The self-attention mechanism models long range interactions at each layer of the neural network, a feature that is absent in most convolutional neural networks. The drawback of the ViT self-attention architecture is that it scales as a quadratic function of the length of the token sequence, and thus scales quadratically with input image resolution. The AFNO provides a solution to the scaling complexity of the ViT. The AFNO model implements a token mixing operation in the Fourier Domain. The computational complexity of the mixing operation is \(\mathcal{O}(N_{token}\log N_{token})\) as opposed to the \(\mathcal{O}({N_{token}^2})\) complexity of the vanilla ViT architecture.

The first step in the architecture involves dividing the input image into a regular grid with \(h \times w\) equal sized patches of size \(p\times p\). The parameter \(p\) is referred to as the patch size. For simplicity, we consider a single channel image. Each patch is embedded into a token of size \(d\), the embedding dimension. The patch embedding operation results in a token tensor (\(X_{h\times w \times d}\)) of size \(h \times w \times d\). The patch size and embedding dimension are user selected parameters. A smaller patch size allows the model to capture fine scale details better while increasing the computational cost of training the model. A higher embedding dimension also increases the parameter count of the model. The token tensor is then processed by multiple layers of the transformer architecture performing spatial and channel mixing. The AFNO architecture implements the following operations in each layer.

The token tensor is first transformed to the Fourier domain with

(41)\[z_{m,n} = [\mathrm{DFT}(X)]_{m,n},\]

where \(m,n\) is the index the patch location and DFT denotes a 2D discrete Fourier transform. The model then applies token weighting in the Fourier domain and promotes sparsity with a Soft-Thresholding and Shrinkage operation as

(42)\[\tilde{z}_{m,n} = S_{\lambda} ( \mathrm{MLP}(z_{m,n})),\]

where \(S_{\lambda}(x) = \mathrm{sign}(x) \max(|x| - \lambda, 0)\) with the sparsity controlling parameter \(\lambda\), and \(\mathrm{MLP(\cdot)}\) is a two layer perceptron with block diagonal weight matrices which are shared across all patches. The number of blocks in the block diagonal MLP weight matrices is a user selected hyperparameter that should be tuned appropriately. The last operation in a ANFO layer is an inverse Fourier to transform back to the patch domain and add a residual connection as

(43)\[y_{m,n} = [\mathrm{IDFT}(\tilde{Z})]_{m,n} + X_{m,n}.\]

At the end of all the transformer layers, a linear decoder converts the feature tensor back to the image space.

There are several important hyperparameters that affect the accuracy and computational cost of the AFNO. Empirically, the most important hyperparameters that should be tuned keeping in mind the task at hand are the number of layers, patch size, the embedding dimension and the number of blocks. Additional information on AFNO and its implementation in Modulus can be found in the example Darcy Flow with Adaptive Fourier Neural Operator.

The Physics-Informed Neural Operator (PINO) was introduced in 12. The PINO approach for surrogate modeling of PDE systems effectively combines the data-informed supervised learning framework of the Fourier Neural Operator with the physics-informed learning framework. The PINO incorporates a PDE loss \(\mathcal{L}_{pde}\) to the Fourier Neural Operator. This reduces the amount of data required to train a surrogate model, since the PDE loss constrains the solution space. The PDE loss also enforces physical constraints on the solution computed by a surrogate ML model, making it an attractive option as a verifiable, accurate and interpretable ML surrogate modeling tool.

We consider a stationary PDE system for simplicity, although the PINO method can be applied to dynamical systems as well. Following the notation used in 12, we consider a PDE represented by,

(44)\[\mathcal{P}(u, a) = 0 , \text{ in } D \subset \mathbb{R}^d,\]

(45)\[u = g , \text{ in } \partial D.\]

Here, \(\mathcal{P}\) is a Partial Differential Operator, \(a\) are the coefficients/parameters and \(u\) is the PDE solution.

In the FNO framework, the surrogate ML model is given by a the solution operator \(\mathcal{G}^\dagger_{\theta}\), which maps any given coefficient in the coefficient space \(a\) to the solution \(u\). The FNO is trained in a supervised fashion using training data in the form of input/output pairs \(\lbrace a_j, u_j \nbrace_{j = 1}^N\). The training loss for the FNO is given by summing the data loss, \(\mathcal{L}_{data}(\mathcal{G}_\theta) = \lVert u - \mathcal{G}_\theta(a) \nVert^2\) over all training pairs \(\lbrace a_i, u_i, \nbrace_{i=1}^N\),

In the PINO framework, the solution operator is optimized with an additional PDE loss given by \(\mathcal{L}_{pde}(a, \mathcal{G}_{\theta}(a))\) computed over i.i.d. samples \(a_j\) from an appropriate supported distribution in parameter/coefficient space.

In general, the PDE loss involves computing the PDE operator which in turn involves computing the partial derivatives of the Fourier Neural Operator ansatz. In general this is nontrivial. The key set of innovations in the PINO are the various ways to compute the partial derivatives of the operator ansatz. The PINO framework implements the differentiation in four different ways.

Numerical differentiation using a finite difference Method (FDM).

Numerical differentiation computed via spectral derivative.

Hybrid differentiation based on a combination of first-order “exact” derivatives and second-order FDM derivatives.

Deep operator network (DeepONet) was first introduced in 13, a network architecture that aims to learn operators between infinite dimensional function spaces. Later a physics-informed version was proposed in 14, introducing an effective regularization mechanism for biasing the outputs of DeepOnet models towards ensuring physical consistency.

Suppose that an operator \(G\) is defined by

(46)\[G:\quad u\mapsto G(u),\]

where \(u\) and \(G(u)\) are two functions. We denote the variable at the domain of \(G(u)\) as \(y\).

As showed in 13, the DeepONet consists of two subnetworks referred as branch and trunk nets. The branch net takes \(u\) as input and outputs a feature embedding of \(q\) dimensions, where \(u=[u(x_1), u(x_2), \dots, u(x_m)]\) represents a function u evaluated at a collection of fixed sensors \(\{x_i\}_i^m\). The trunk net takes the coordinates \(y\) as the input and also outputs a feature embedding of \(q\) dimensions. The final output of DeepONet is obtained by merging the outputs of the branch and trunk nets via a dot product.

The plain DeepONet is trained in a supervised fashion by minimizing a summing data loss \(\mathcal{L}_{data}(\mathcal{G}_\theta) = \lVert \mathcal{G}_\theta(u)(y) - \mathcal{G}(u)(y) \nVert^2\) over all training input output triplets \(\lbrace u_i, y_i, G(u_i)(y_i) \nbrace_{i=1}^N\). The physics-informed DeepONet is trained with an additional PDE loss given by

(47)\[\mathcal{L}_{pde}(\mathcal{G}_\theta) = \lVert \mathcal{N}[\mathcal{G}_\theta(u)](y) \nVert^2\]

where \(\mathcal{N}\) is a differential operator denoting the governing PDE of the underlying physical laws.

It is worth mentioning that users have flexibility to choose the architecture of branch and trunk net. For example, CNN can be used as a backbone of the branch net to extract features from high-dimensional data. This will be more efficient than a fully-connected neural network as has been mentioned in 13.

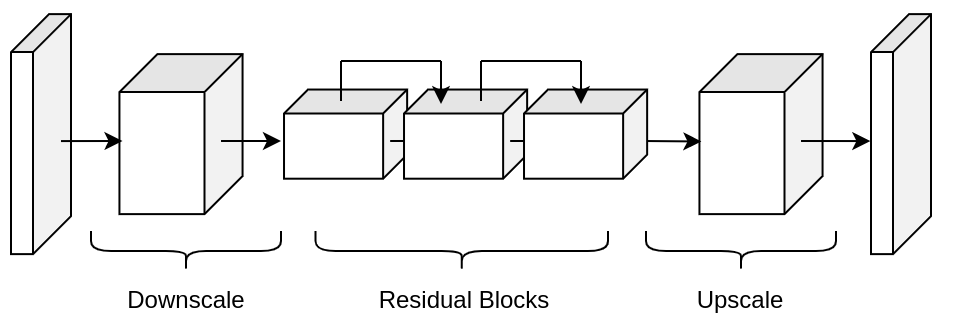

Pix2Pix network in Modulus is a convolutional encoder-decoder based on the pix2pix 15 and pix2pixHD 16 generator models. The implementation inside of Modulus is a streamlined version of these models that can be used for various problems involving data that is structured. This model consists of three main components: downscaling layers, residual blocks and upscaling layers.

The downscaling part of the model consists of a set of \(n\) convolutions that reduce the dimensionality of the feature input. Each layer consists as a set of convolutions with a stride of 2, normalization operation and activation function \(\sigma\):

(48)\[z = (\textrm{Conv}(s=2) \circ \textrm{BatchNorm}(\cdot) \circ \sigma(\cdot))^{\circ n}(x).\]

The middle of the model consists to \(m\) residual blocks of the following form:

(49)\[z = \left(\textrm{z}_{i} + (\textrm{Conv} \circ \textrm{BatchNorm}(\cdot) \circ \sigma(\cdot) \circ \textrm{Conv} \circ \textrm{BatchNorm}(\cdot) \circ \sigma(\cdot))\night)^{\circ m}(z),\]

where \(\textrm{z}_{i}\) indicates the output from the previous convolutional block. Lastly, the upscaling section mirrors the downscaling section with transposed convolutions:

(50)\[y = (\textrm{ConvT}(s=2) \circ \textrm{BatchNorm}(\cdot) \circ \sigma(\cdot))^{\circ n}(z).\]

The pix2pix encoder-decoder also allows users to upscale the resolution of the input output feature with an additional set of transpose convolutional layers. Information regarding using this model in Modulus can be found in the example Turbulence Super Resolution.

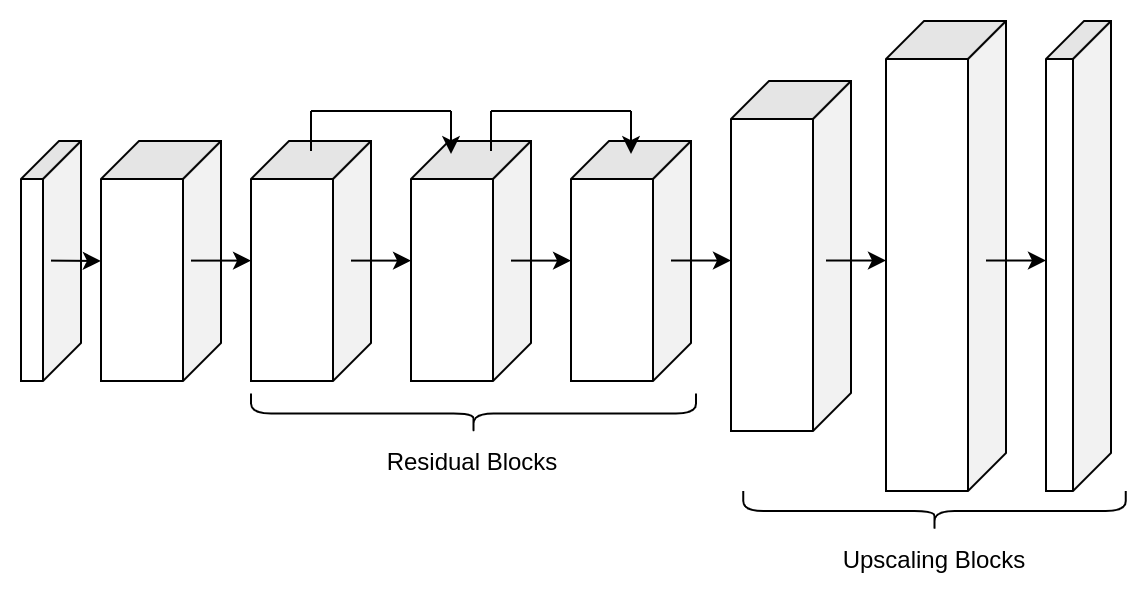

The super resolution network in Modulus is a convolutional decoder that is specifically designed for super resolution problems 17. This model can be particularly useful for mapping between low to high resolution data that is on a structured grid. This model consists of just two parts: convolutional residual blocks and upscaling blocks.

The front of the model consists to \(m\) residual blocks consisting of two standard convolutional operations, normalization, and activation function \(\sigma\):

(51)\[z = \left(\textrm{z}_{i} + (\textrm{Conv} \circ \textrm{BatchNorm}(\cdot) \circ \sigma(\cdot) \circ \textrm{Conv} \circ \textrm{BatchNorm}(\cdot) \circ \sigma(\cdot))\night)^{\circ m}(x),\]

where \(\textrm{z}_{i}\) indicates the output from the previous convolutional block. The second part of the model consists of \(n\) upscaling blocks which each consist of a convolutional operation, a pixel shuffle upscaling and activation function.

(52)\[y = (\textrm{Conv} \circ \textrm{PixShuffle}(s=2) \circ \sigma(\cdot))^{\circ n}(z).\]

Each upscaling layer increases the dimensionality of the feature by a factor of 2. Additional information regarding this model and its use in Modulus can be found in the example Turbulence Super Resolution.

References

Rahaman, Nasim, et al. “On the spectral bias of neural networks.” International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2019.

Mildenhall, Ben, et al. “Nerf: Representing scenes as neural radiance fields for view synthesis.” European conference on computer vision. Springer, Cham, 2020.

Tancik, Matthew, et al. “Fourier features let networks learn high frequency functions in low dimensional domains.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33 (2020): 7537-7547.

Wang, Sifan, Yujun Teng, and Paris Perdikaris. “Understanding and mitigating gradient flow pathologies in physics-informed neural networks.” SIAM Journal on Scientific Computing 43.5 (2021): A3055-A3081.

Srivastava, Rupesh K., Klaus Greff, and Jürgen Schmidhuber. “Training very deep networks.” Advances in neural information processing systems 28 (2015).

Sitzmann, Vincent, et al. “Implicit neural representations with periodic activation functions.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33 (2020): 7462-7473

Sirignano, Justin, and Konstantinos Spiliopoulos. “DGM: A deep learning algorithm for solving partial differential equations.” Journal of computational physics 375 (2018): 1339-1364.

Fathony, Rizal, et al. “Multiplicative filter networks.” International Conference on Learning Representations. 2020.

Wang, Sifan, Hanwen Wang, and Paris Perdikaris. “On the eigenvector bias of fourier feature networks: From regression to solving multi-scale pdes with physics-informed neural networks.” Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering 384 (2021): 113938.

Li, Zongyi, et al. “Fourier Neural Operator for Parametric Partial Differential Equations.” International Conference on Learning Representations. 2020.

Guibas, John, et al. “Adaptive fourier neural operators: Efficient token mixers for transformers” International Conference on Learning Representations, 2022.

Li, Zongyi, et al. “Li, Zongyi, et al. “Physics-informed neural operator for learning partial differential equations.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2111.03794 (2021).

Lu, L., Jin, P., Pang, G., Zhang, Z. and Karniadakis, G.E., 2021. Learning nonlinear operators via DeepONet based on the universal approximation theorem of operators. Nature Machine Intelligence, 3(3), pp.218-229.

Wang, S., Wang, H. and Perdikaris, P., 2021. Learning the solution operator of parametric partial differential equations with physics-informed DeepONets. Science advances, 7(40), p.eabi8605.

Isola, Phillip, et al. “Image-To-Image translation With conditional adversarial networks” Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2017.

Wang, Ting-Chun, et al. “High-Resolution image synthesis and semantic manipulation with conditional GANs” Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2018.

Ledig, Christian, et al. “Photo-Realistic single image super-resolution using a generative adversarial network” Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2017.